Juna Mozda: Letters, Land, and the Learning of Belonging

This narrative traces a long, inward journey toward Mozda, a tribal village nestled in the Satpuda ranges of Gujarat. Woven through letters written over three decades by Swati and Michael, the essay reflects on land, community, and a way of life shaped by generosity rather than accumulation. Moving between memory, imagination, and lived encounter, it is less a travelogue than a meditation on belonging, responsibility, and the fragile persistence of human values in a world increasingly governed by speed, profit, and forgetting.

Some places enter our lives long before we arrive there. They come to us as stories, as letters written in careful handwriting, as quiet conversations that refuse to fade. Mozda reached me in this way, not as a point on the map, but as a presence that slowly took root in my imagination. Long before I walked its paths or spoke to its people, Mozda had already begun to question my certainties: about progress, belonging, and what it means to live well. This narrative is not about discovering a village; it is about being prepared, over time, to listen to one.

I first heard of Juna Mozda in 2015. Not through a map, not as a destination to be reached, but as a choice spoken of gently by Swati Desai during a visit to Vadodara, where she hosted Jyotibhai Desai. Swati spoke of Mozda as one speaks of a life decision: deliberate, uncertain, and deeply felt. She and her partner, Michael, had travelled across India on a two-wheeler, searching not for comfort or opportunity but how to look for a village where they could live and how to perceive work. Their journey was guided less by routes and more by listening: to land, to people, and to an unease with the world they had inherited. And to learn from the experiences of the many who walked a similar path.

By then, I was not entirely unfamiliar with village life. My social work experiences in Nagpur and Gorakhpur had offered me fragments-glimpses of rural rhythms, of labour that begins before speech, of silences that hold memory. Yet I also knew that villages are not interchangeable landscapes. Each one carries history differently, breathes time at its own pace. What moved me most, however, was not Mozda itself, but the courage and tenderness of choosing a village as one chooses a way of being and arriving there slowly, leaving room for uncertainty to remain alive.

My meeting with Jyotibhai marked a quiet turning point in my life. Over time, he became a friend, and perhaps a philosopher, though for reasons that resist clear articulation. Our conversations unfolded gently, without an agenda. One day, Swati shared with me the letters she and Michael had been writing to their friends about life in Mozda. There were twelve of them. I read them slowly. They were vivid, restrained, and unsettling in their beauty. Long after I had finished reading, they stayed with me.

Mozda began to take shape in my imagination, not as a fantasy, but as an inner geography. Looking back, I realise those letters deepened my connection to indigenous communities in a way that was neither ideological nor academic. It was something more elemental, an emotional recognition. The people Swati wrote about lived close to nature and closer still to one another. Meaning there did not emerge from accumulation, but from presence; not from control, but from attention. Their lives seemed guided more by the heart than by calculation.

At that time, I had not yet encountered Noam Chomsky’s assertion that indigenous people may be our last hope for survival. But the truth of that thought had already reached me quietly, through Mozda. Not as theory, but as feeling.

After reading the letters, I longed to visit Mozda. I would occasionally share this desire with Swati over the phone. She always responded with warmth, as though Mozda was not merely a place she lived in, but one she wished to share. Yet my own limitations intervened. The journey remained deferred, suspended somewhere between intention and circumstance.

Still, Mozda did not leave me. It returned during moments of cynicism when faith in humanity felt thin, when life appeared weighed down by excess and cruelty. Mozda reminded me that another way of living was possible: a life not needlessly complex, where emotions could reach the heart without mediation, where existence was about becoming rather than having. For a long time, it remained a distant village and a quiet refuge in my mind.

That long-held desire finally found its moment when my friend Saji P. Mathew asked if I could accompany him to Vadodara, to stay with our friends Chinnan and Reshmimala. This time, the circumstances were generous. I had enough days not only to stay in Vadodara, but also to travel to Mozda with Swati.

I’m sharing a summary of that experience. Brief, not because it was small, but because some experiences resist full narration. Alongside what I saw in Mozda, I also carried what I had read years earlier. I wish to place these together to reflect on the matches and mismatches between memory, imagination, and lived reality.

Mozda lies within the forested folds of the Satpuda Range, one of the ancient mountain systems of central India, through which flows the life-giving river Narmada. The village is situated about 25 kilometres south of the river. According to Swati and Michael, Mozda itself is the result of a quiet historical movement: nearly a hundred years ago, communities living closer to the Narmada began migrating deeper into the hills, seeking land, forest, and a measure of autonomy away from external control. Over time, these settlements took root, and Mozda came into being—not as a planned habitation, but as an organic extension of people learning to live with the rhythms of mountains, forests, and distance.

Before moving further, it would be unfair not to return to the letters Swati and Michael wrote during their early days in Mozda. The first letter, written in December 1991, was titled She Is Our Daughter Too. The title itself reveals the depth of what Mozda came to mean for them.

The opening lines remain unforgettable:

“About twenty-five adults and fifteen teenagers (all males) are haphazardly sitting on a verandah, and an animated discussion is going on. The subject: when and how we should celebrate Diwali, one of the two most important festivals in the region. An elder suggests that there be no dancing this year, as there have been two deaths in a single family. The whole village should show at least a token participation in their grief.”

Later, in Mozda, Swati explained that festivals like Holi or Diwali are not fixed by calendars alone. They are shaped by collective deliberation and shared circumstances. Celebration here is not an obligation imposed by time; it is a response to life as it unfolds. In 1991, the village chose to stand with grief rather than insist on festivity.

In the same letter, Michael writes:

“We have found that the people have certain exceptional qualities-honesty, generosity, trust, faith, love and these make them so beautiful. Before we noticed, they had taken us into their families… One of the neighbours told Swati’s mother that she need not worry anymore, because Swati is their daughter too.”

There is little one can add to these words without diminishing them.

Another letter narrates how their home in Mozda was built not through contracts or wages, but through collective presence:

“All of a sudden, three men appeared with a lot of bamboo and began weaving the walls… When we offered to pay them, they would not name an amount. When we paid them the minimum wage, they returned some of it, saying that now ‘you belong to the village’.”

In those days, building a house was a shared responsibility. There was no wage as such—only food, and sometimes mahua, the local country liquor, shared in the evening. The houses were ecologically rooted: mud, bamboo, and country tiles. Except for the tiles, everything came from the forest or the village itself.

Today, much of this has changed. Materials from outside have entered Mozda, bringing new dependencies and altered ways of living. But the memory of that earlier time, when belonging preceded ownership, still lingers quietly, resisting erasure.

In another letter, Michael recounts an episode that, at first glance, appears almost comic, but on closer listening reveals a different moral universe. When Swati travelled to Australia, the people of Mozda struggled to comprehend such a prolonged absence from home. Distance, for them, was not abstract geography; it was emotional rupture. Concerned and with complete seriousness, they advised Michael to marry another woman. In their understanding, Swati had been “stolen.”

An urban, modern sensibility might dismiss this as ignorance, as proof of isolation from the wider world. But it can also be read otherwise as an expression of care shaped by a worldview in which absence demands resolution, where companionship is not optional, and where life is approached without layers of explanation. There is a quiet beauty in that simplicity. Not innocence, but a directness of seeing life uncluttered by excess interpretation.

In the early days, Swati and Michael had not yet begun practising agriculture themselves. Yet they were never strangers to the world of sowing and harvest. Life in Mozda unfolded within a moral economy governed not by profit or calculation, but by generosity and shared survival. The community functioned on trust rather than transaction, on giving rather than accumulation.

Their first letter bears gentle witness to this ethic of abundance amidst scarcity:

“After this year’s crop was harvested, people themselves came forward to give us this year’s grain. It is a custom of this area that anyone who goes to the winnowing place is given some grain as a gift. It is called tax, but we did not go, as the harvest this year was not very good. Still, people from our cluster came forward to give two or three kilos of every crop! It is amazing how much love they can give and how generous they can become even when they have so little.”

What they encountered was not charity, but a way of life in which grain circulates as affection, and survival is collective rather than competitive.

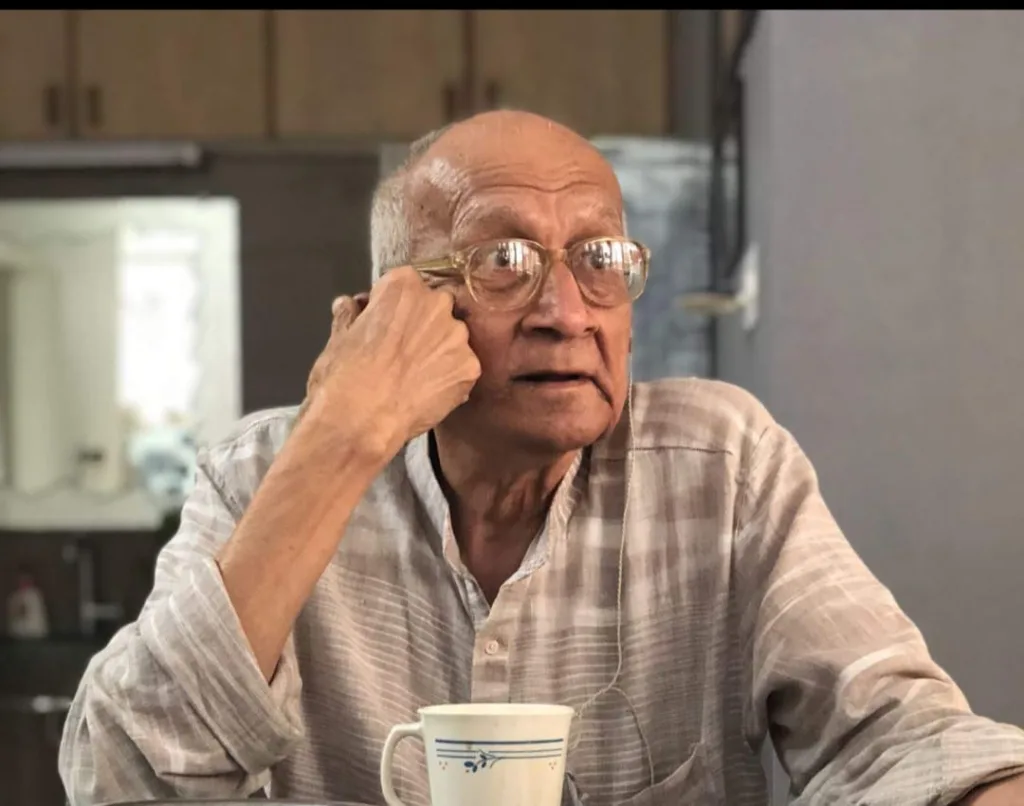

Their fifth letter, The Field Has a Soul Too, reveals the community’s relationship with land—an intimacy that modern agrarian language can barely contain. Written with tenderness and wonder, the letter recalls a winter morning:

“Once we were sitting with Gurji, a neighbour, early in the morning, overlooking some fields planted with chickpeas. It was quite cold, and we were not really up to talking much. But we noticed that in the field, though all the chickpeas were planted in east–west rows, one row cut across the field diagonally. So we asked him why. After much coaxing, he said that it is the soul of the field.”

They were taken aback. They had expected an explanation rooted in technique or experience. Instead, what emerged was a cosmology in which land is not inert matter, but a living presence that must be acknowledged, honoured, and given room to breathe. In that single diagonal row lay a philosophy refined over generations: an ethical relationship with land that modern agriculture has largely forgotten.

By September 1997, in their seventh letter, Community House Building, a more anxious note entered the narrative. The letter reflects their growing unease about the transformations unfolding around Juna Mozda-changes whose consequences continue to echo today:

“Liberalisation and globalisation of economic policies and industries are having very serious long-term effects on our society. Some development is definitely visible, but capturing fundamental common property resources like land, forest, and water is going on at a much more rapid pace. Economic disparity is increasing social tension and general discontent.”

This was not abstract theory. It was a lived reality felt in shrinking commons, poisoned water, and the slow fraying of community bonds.

In their tenth letter, written in May 2001, they speak of a young man from the village, Eswar whom we would later meet in Mozda. With quiet pride, they write:

“One of our gains from a decade of work in Mozda is Ishvar. Not the Ishvar (God, in Gujarati) many of us seek, but a quiet, hardworking, sincere young man of Mozda who has started working with us.”

Here, transformation is not measured in projects completed or reports written, but in relationships forged; human beings growing into confidence, responsibility, and collective purpose.

The same letter turns sharply to the devastation caused by unregulated industrial growth:

“Studies done during the people’s tribunal we organised last year showed that groundwater pollution had reached serious dimensions across the whole Golden Corridor. And for the last two years it has rained very little. So we carried out more detailed investigations in Vapi and Ankleshwar over the last four months and brought this to the notice of the Gujarat Pollution Control Board.”

Behind the measured language lies a stark truth: poisoned aquifers, parched lands, and a model of development that feeds distant profits while hollowing out local life.

Their final letter, Taking Responsibility – Learning to Lead, written in May 2003, arrives heavy with moral reckoning. Its opening lines carry both resolve and grief:

“Whatever be our shortcomings and limitations, we belong to a community that believes in the efficacy of virtue and in trying to do our best for a better society… Yet, for the first time, something fundamental changed in what we are.”

The violence of 27 February 2002 and the carnage that followed in Gujarat shattered any remaining illusions. What shook them most was not only the brutality itself, but the role of the state and the chilling pride with which sections of the middle class justified the violence. The letter speaks of a xenophobic atmosphere, of truths twisted and victims blamed, of women and children reduced to footnotes in a perverted public discourse. It asks a question that refuses easy answers: where does one go when the most basic value of life is abandoned?

They used to write twice a year. After that final letter, no more came from Mozda to their friends.

When the letters finally stopped, Mozda did not fall silent. It continued in the lives Swati and Michael chose to live, in the land that still carried its diagonal line of breath, and in the memory of a community that knew how to give without counting. What Mozda offers is not a lesson easily summarised or a model to be replicated. It is a reminder, fragile yet persistent, that another way of being human has always existed alongside the world we call modern. To remember it, perhaps, is the first act of responsibility.

(to be continued)