Lynching as Spectacle: The Street Performance of Violence in India

Harsh Mander is a powerful voice for justice in India. An extraordinary figure, he resigned from the Indian Administrative Service to devote his life to the legal and social struggles of ordinary citizens, particularly those affected by communal and ethnic violence. In the first part of this interview, he speaks about how the Sangh Parivar regime is eroding constitutional values, fostering hatred and division, and enabling the rise of mob lynchings as a disturbing new norm.

Part One

9 Minutes Read

How do you feel today when you think about your decision to resign from the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) in 2002 and enter the field of social work full-time?

In 2002 – after the horrific Gujarat state-sponsored massacre – many people like me realised how gravely threatened democracy was in our country, India, and the values it upholds such as equality, justice, and brotherhood. It was a time when we realised that our perceptions were shattered that secular and multi-cultural democracy in India were secure. Before 2002, I was fulfilling my constitutional duties by holding various responsibilities in government service. I left the IAS because of my conviction that the constitution was itself in danger. I could in these circumstances no longer continue to be a part of the government. Instead I decided to work for my country as an ordinary citizen.

In the years that have passed, especially after 2014, seeing where the country has headed, I realized that that decision was a very appropriate one.

Did you feel at the time that the Gujarat communal riots might have an impact on other parts of India and that India might fall into the hands of Hindutva fascist forces, as we see today?

2002 was not the first communal massacre in India. There were massacres in Nellie in 1983, Delhi in 1984, Bhagalpur in Bihar in 1989, and Bombay in 1992. These climaxed in the Gujarat massacre of 2002, which brutally targeted women and children across the state, supported at every step by the state. That is why the violence went unchecked in about twenty districts for weeks. The brutal atrocities against women and children in Naroda Patiya, the atrocities against Ehsan Jafri, etc., showed the role of the state administration. The state could have controlled the riots within hours, but it did not do that.

After the communal massacre, the state did not even fulfil its basic constitutional duties by setting up relief camps for two lakh people who had been displaced from their homes by their violence. When questioned about this, Chief Minister Modi responded in very derogatory language, saying, “I do not intend to start a baby-producing factory.” The central government, led by Vajpayee, also did not intervene effectively. The victims also were not given adequate compensation. The Sangh Parivar’s effort, enabled by the entire local criminal justice system – the police, the prosecution, and the courts – was to sabotage all avenues in the fight for justice. They also boycotted the Muslim residents and expelled them from mixed habitations.

The Delhi riots of 2020 were handled even worse by the central and state government. It was something that could have been stopped within hours, but went on for three days.

In this situation, I could only fight for justice as a free citizen, not as an official of the government.

Were there any specific experiences during your childhood or while in government service that inspired you to develop an uncompromising attitude toward social justice and democracy?

The answer to that is not easy to give. Ours is a family that experienced the violence of the partition of India and Pakistan. My parents lived in Rawalpindi. Perhaps the enormous suffering my extended family experienced at that time has passed into my DNA. Even in my youth, I had the urge to support suffering people and speak out against injustice. The values instilled by my family and the schools that raised me have influenced me. Also, the time I grew up in as a child was one of idealism. Interestingly, the people who directly experienced the tragedies of partition later have stood most firmly for human brotherhood and sisterhood. That is why Punjab and West Bengal are standing most firmly today against the RSS agenda of hate and division.

Can you tell us about the activities of the Caravan of Love group that you lead?

In the first five years of Modi’s tenure as Prime Minister, mob lynchings were widespread. Most Indian languages did not even have a word for lynching, except Bengal where pickpockets were lynched for many years. In other places, it was a new trend. It was a very specific kind of violence. It was not just collective murder. It was a street performance of brutal violence. A crowd would witness the lynching with the ease of a carnival. Such atrocities against Black people were common in America. There would be a large crowd, including children, to witness it all. So each murder would have the impact of a thousand murders, spreading fear in the hearts of all Black people. Now, videos of such incidents are also being circulated to millions. The videos travel to our phones and homes and create hatred and cruelty in the minds of tens of thousands of people. They also create fear in the minds of every Muslim. The number of people killed in such incidents across the country may be fewer than just in a single communal massacre like the Gujarat riots, but the impact is much wider. After one Muslim youth was lynched on a train in Delhi, Muslims across the country are today afraid to travel on trains. The first Modi government’s big ‘contribution’ to tear apart India’s social fabric or religious goodwill was lynching.

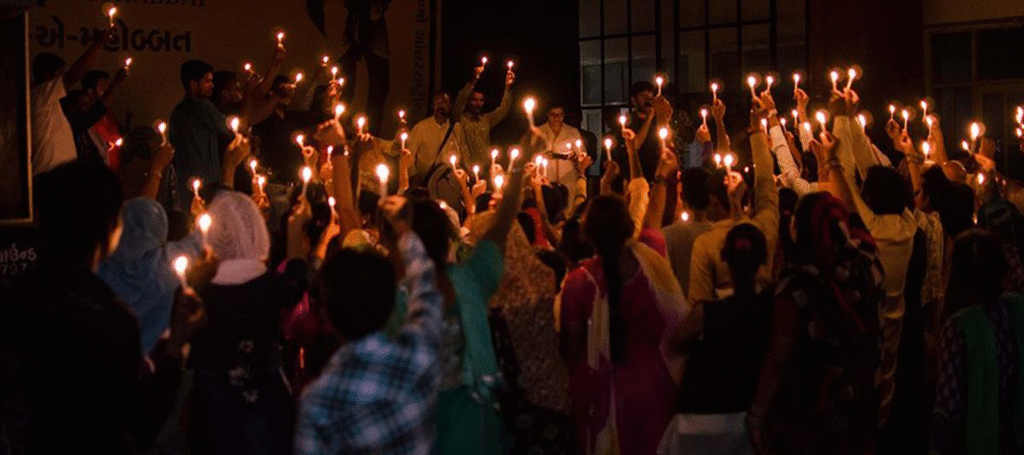

The government stands by as a silent witness to such incidents, and the general public follows it. This must end. The lesson taught by great moral leaders like Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, and Martin Luther King is that hate cannot be fought with hate. It can only be fought with love. Learning from them, I wrote of my plan to start a Caravan of Love to counter hate first in my column in The Indian Express. My call to join this campaign received a good response from various sections of people, including students, lawyers, social workers and even training priests. In this way, the Caravan of Love or Karwan e Mohabbat began in September 2017 with a month-long journey beginning with the home of a family that lost two loved ones to lynching in Assam, and ending on October 2 at Porbandar, the coastal town where Gandhiji was born. During that trip, we visited each family of the victims of lynching. It was not about finding out the facts or preparing reports. It was like visiting a friend’s family who had suffered this tragedy. That visit helped share the family’s pain and overcome their isolation. It also helped express solidarity in the fight for justice. We have since then completed more than 50 such journeys to different corners of the country. And each visit to a family that lost loved ones to lynching doesn’t end with a visit. It’s also about building a long-term relationship of trust and care with that family. We’ve been able to form a community of people working with us at the state and local levels in places where such incidents are more common. We’ve started to help with legal cases, pensions, and more. We’ve been able to write about those experiences and make short films.

Can you talk about the response you receive from families of victims of lynchings during such visits?

It is a process of building lasting human relationships based on love and care. This is not the first time this has happened in our country. Gandhiji did the same thing whenever such incidents occurred. He was not in Delhi when India got independence, he was in Calcutta with people suffering from the communal riots. The Karwan is humbly trying to follow in his footsteps.

There are many vital differences between lynchings and communal riots. Since communal riots target a group of people, a community of victims is created, and therefore, the victims may receive support from each other and their community. In a lynching, a family often has to bear all the pain alone. Often, even their community is hesitant to stand by them due to fear. That is why we try to make such families understand that they are not alone and ensure local support for them.

Does the government create obstacles when such activities are carried out?

Of course. Efforts are being made to obstruct us as much as possible. There are currently a large number of criminal cases investigated and registered against me, including of supporting terror, money-laundering, hate speech and much else. Funding for our organization has been stopped. But our resolve is that nothing the state does will silence my voice, my conscience and my work.

What is the lesson learned from such activities?

One, many families said that if the victim had been killed instantly instead of being tortured to death over a long period, their loved one would not have had to endure so much pain. Sometimes a person is tortured to death for hours. I have seen in many videos how, in many instances of lynching, people ask for water before dying, and the murderers refuse to give this to them.

Another observation is that when such murders take place, no onlooker comes forward to stop them. Then there is the passive involvement of the police, who merely watch and, in many cases, assist the murderers. What they do after the murder is even worse. They often follow the practice of making the family of the murdered person an accused in multiple cases. Sometimes, the police even register the FIR incorrectly or not at all, recording it as an accidental death. They are not even willing to record the dying declaration of the victim in the hospital. Even when video evidence of the murder is widely circulated, they do not accept it as valid proof.

By the time Modi’s second term began, such violence was already on the rise. Cow protection groups had by then begun working directly with the police. The government started recognizing them as social activists in the name of cow protection, which gave them tremendous power.

When a Hindu man was killed in Delhi under the mistaken belief that he was a Muslim, the attackers said, sorry, it was a mistake. The victim’s mother asked: “If he had been a Muslim, would that not have been a crime?” When a Muslim is killed, the justification becomes that he was smuggling beef. And yes, when a Muslim kills someone, he is branded a terrorist. Our language has become so divisive. A person who commits murder in the name of cow protection or “love jihad” becomes a hero.

Another change is in the weapons used in these killings. Instead of stones and sticks that were used in earlier lynchings, modern weapons are now being used. These incidents are even being streamed live on social media.

Have the perpetrators experienced feelings of guilt or remorse after such murders?

I have never seen such remorse. Let me tell you about one experience. The day marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Masjid. An incident took place in Udaipur, Rajasthan, which was deeply disturbing. A man decided to “celebrate” the anniversary by killing a Muslim. He asked his nephew to record the incident on video. He phoned a Muslim construction worker from Bengal were working saying he had some work for him. As soon as he arrived, he brutally beat him until he lost consciousness, and then sprinkled petrol on him and set him on fire. All of this his teenaged nephew filmed. Then he stood in front of the camera and gave a long hate speech against Muslims.

We later visited the family of the man who committed this murder. They were from the Dalit community. The murderer, we learned, was despondent after his business collapsed after demonetization. He then began watching anti-Muslim videos daily. Gradually, he got into a state of mind where he believed he needed to kill a Muslim.

But the only thing that bothered his family was that their younger nephew had been made an accomplice. They told us the murder was justified, citing “love jihad.” When I asked for a real-life example of such an incident, they couldn’t give one. Eventually, they mentioned three consensual relationships between a Hindu and a Muslim that had taken place over the last fifteen years.

What followed was even more disturbing. The villagers had erected a statue in a tableau for Dassahra which depicted the killer like a god trampling the man he killed to death. Depicting him as a demon.

When we visited the home of the murdered young man in Bengal, we found his family struggling to raise his only daughter.

Hate speech has spread like an epidemic since Modi came to power. What can be said about it?

Yes, hate speech has grown into a major epidemic that we are facing today. We are trying to work against hate propaganda. The German people who survived the Holocaust have said that genocide did not begin in gas chambers; it began with hate speech.

If Hitler was responsible for the Holocaust in Germany, today our Prime Minister is playing a similar role in India in raising hate against Muslims to such a high level, resulting in hate crimes and lynching.

We now have systems like WhatsApp that spread hate rapidly. The doses of hatred injected into people’s minds daily make them angry and violent. No one is punished for for hate speech. Not a single FIR has been filed against Kapil Mishra, who made hate speeches that sparked off the Delhi riots. Today, he is the Law Minister of Delhi.

Moreover, social media is actively collaborating in spreading Hindutva propaganda. The BJP is reaping the benefits of all this during elections. There is an organization in Maharashtra that regularly organizes hate rallies. I have approached the court against Sanjay Nirupam, who said that another Jallianwala Bagh would be repeated against Muslims.

The only consolation is that in the 2024 elections, the NDA alliance lost in every one of the constituencies where Modi made hate speeches.

Credit: Chandrika Weekly, June 2025

Cover Image: Activists of Hindu Sena protest against a government inquiry’s conclusion that Mohammed Akhlaq, victim of mob lynching in Uttar Pradesh, was not storing beef for consumption

Credit: https://www.aljazeera.com/

(To be continued)