Tagore and the Brahmanical Roots of Cultural Nationalism

By juxtaposing Tagore’s elitist idealism with the emancipatory traditions of thinkers like Jyotirao Phule, B.R. Ambedkar, Ayodhidasa, Periyar, and Sahodaran Ayyappan, Dr. Radhakrishnan Ilayidath’s article explores a radical counter-narrative of fraternal nationalism rooted in anti-caste ethics, Buddhist humanism, and labor-centered epistemologies. The article offers a critical engagement with Dr. E. Ratheesh’s pathbreaking thesis on cultural nationalism and its subaltern countercurrents.

Part 2

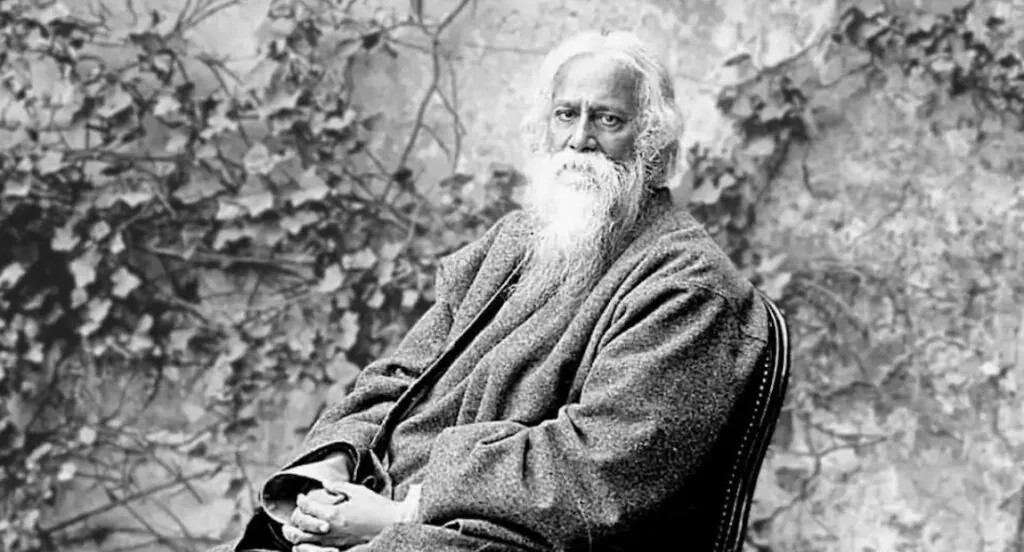

Criticism of Tagore

As part of the critique of cultural nationalism, the thesis provides a close examination of Tagore. His views emerged in the context of the destructive developments, wars, and intense nationalist ideologies of Western nations. Tagore regarded nationalism as a deadly disease, highlighting its inherently violent nature. Brahmanical philosophies had a deep influence on him. He portrayed the East as a symbol of humanity. While certain aspects of Tagore’s critique of nationalism are acceptable, the alternatives he proposed are entirely unacceptable, as they are rooted in a Brahmanical valorization of the ancient.

The researcher argues that viewing nationalism as a wholly destructive process is historically inaccurate. He points out the irrationality, historical denial, partisanship, and sense of otherness present in Tagore’s perspective. The tension within Tagore lay between an aggressive Western nationalism and an Indian-ness that had internalized this dominance. Tagore believed that science and commerce disrupted the moral balance of human life. He positioned scientific consciousness as the political opposite of mythic fundamentalism. To Tagore, science was a threat that dismantled traditional occupational structures. The reality of the ideal villages envisioned by Tagore was entirely different from what was envisioned.

Tagore justifies the caste system. His view is that caste avoided conflicts and ensured maximum freedom for everyone within their boundaries, thus resolving the racial question. He tells the West that Indians should only be questioned on caste after abolishing untouchability in their countries. Compared to the West, India addressed racial issues with greater tolerance, something the West failed to understand. Tagore opposed the Communal Award, considering it a dangerous threat to national unity. The thesis argues that while Gandhi exerted his full energy against untouchability, Tagore’s focus was on portraying Muslims as the ‘other’. Tagore failed to realize that revivalist ideas could lead to communal polarization. Ultimately, it was the consciousness of Brahmanical Hindutva, presenting a deeply unequal and unjust hierarchical order as a global model, that manifested through Tagore.

Tagore’s view of women is grounded in nature-based value judgments that distinguish between men and women, reinforcing these through a mythological framework. The task of restoring lost culture is turned into a historical duty assigned to women, who are portrayed as ideal models. Tagore adopts a stance that sees Hinduism through an Aryan-Dravidian lens, treating Buddhism lightly. Even when acknowledging that Brahmanical dominance led to Buddhism’s decline, Tagore depicts it as a self-inflicted purity-induced disappearance. He reflects the Brahminical appropriation that reimagines the Buddha as the third avatar of Vishnu. Tagore also makes the historically inaccurate claim that Buddhist thought is of Aryan origin.

He lamented the loss of Eastern, village-based education systems and saw the need for an Eastern university as rooted in this concern. The researcher argues that Tagore’s interventions ultimately reinforced upper-caste ideals of Indian nationalism. “Tagore engaged the world about India from the position of the highest caste capital embedded in India’s hierarchical social order. His invocation of ancient philosophical wisdom, sage traditions, mythological literature, and the portrayal of Indian villages as ideal republics—along with his blanket opposition to Western modern philosophical thought—positions him as the popular face of a ‘cultural-nationalist traditionalism’ that seeks to universalize these as the foundational values of Indian culture” (2022:50).

Fraternal Nationalism

Fundamental critiques of cultural nationalism and Hindutva have emerged from subaltern communities. The anti-caste and pro-women struggles that spread across India in the 19th century are part of this tradition. While uncovering the history of subaltern renaissance and fraternal nationalism, the thesis draws upon the ideological concepts of Slavoj Zizek. It presents a wide array of figures—Jyotirao Phule, B. R. Ambedkar, Ayodhidasa, Periyar, and Sahodaran Ayyappan—as key voices of fraternal nationalism. These thinkers challenged narrow nationalist imaginaries, such as Aryavarta, Akhand Bharat, and Ram Rajya, by advancing counter-imaginaries, including Bahishkrit Bharat, Bali Rajya, and Prabuddha Bharat. The hallmark of this intellectual tradition is compassion, solidarity, and equality—values fundamentally opposed to Brahmanism.

It was an intellectual-critical tradition that made the Indian renaissance possible by subverting both racism and caste, and this tradition lies at the very origin of Indian nationalism. At its core is the Jyotirao Phule–Ambedkar stream, which stood in clear opposition to cultural nationalism and religious fundamentalist nationalism. This tradition has its roots in Buddhist thought. While it was Ambedkar who brought Buddhist philosophy into the national mainstream, thinkers like Ayodhidasa and E.V. Ramasamy Naicker (Periyar) also played key roles in making it nationally relevant. The idea of a “national intellectual tradition rooted in Buddhism” does not manifest as a single organization or a fully formed ideology. Nor can this intellectual advance be confined to a specific historical phase.

The thesis highlights how, within the Hindu reformist projects of cultural nationalism, women were recast as guardians of tradition and caste-based domestic purity. In contrast, it argues that the real impetus for women’s education in India came from subaltern, non-Brahmin movements. Phule directly challenged traditional norms and beautification ideals imposed on women by leading them out of ritualistic confines and asserting their freedom through modern education. The thesis contends that these subaltern movements served as the true model even for nationalist reformers. It also points to Ambedkar’s introduction of the Hindu Code Bill in 1949, which emphasized women’s civil rights and gender equality, as a landmark intervention in this trajectory.

Ambedkar’s (1892–1956) primary critical engagements were with literary sources. In his view, the Vedas and Puranas served to legitimize a violent and oppressive social order. The enduring relevance of Ambedkar lies in how his deep critical consciousness evolved into a politically transformative awareness for India’s oppressed populations. From the era of the national freedom struggle, Ambedkar’s thought expanded into a comprehensive, knowledge-based critique that spanned history, culture, religion, economic theory, concepts of nationalism, and constitutional values. This body of thought functions as an intellectual center for envisioning an India rooted in equality, fraternity, and democracy. It consistently challenges dominant cultural and racial ideologies that seek to impose Brahmanical homogeneity on India, threatening its pluralistic and secular heritage.

Ambedkar gave voice to the experiential world of the marginalized communities excluded from Vedic entitlement. He exposed the internal fractures within Aryan society and rejected the notion that India was the rightful domain of Aryan sovereignty. He refuted the authority of the Vedas, denounced ritualistic yajnas, and resisted the caste system, aligning himself with the Buddha’s standpoint. While the cultural-nationalist stream saw the Bhagavad Gita as a product of Brahmanical philosophy, Ambedkar viewed Buddhism as a viable alternative to it. Embracing the Buddha as a guiding figure, Ambedkar rejected rigid and eternal doctrines, placing his faith instead in the fundamental capacity of human beings. Like the Buddha, he dismissed the Upanishadic concepts and the metaphysical idea of Brahman.

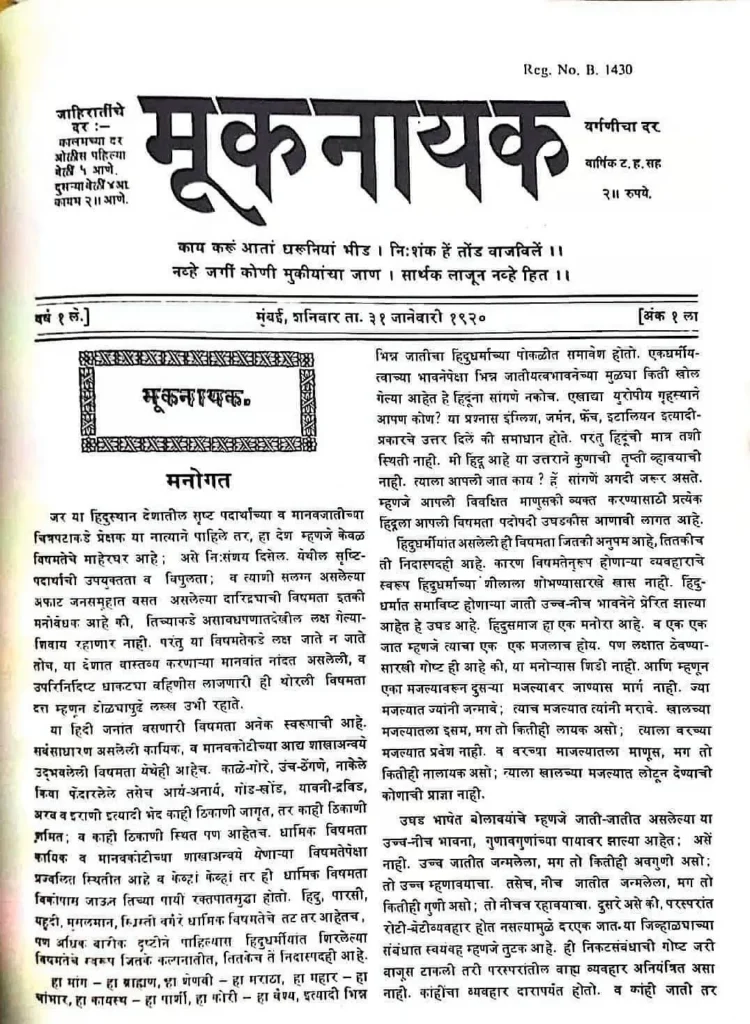

The thesis highlights the significance of Mook Nayak, the newspaper through which Ambedkar critiqued both the Congress and Hindu nationalist ideologies. It notes that several other journals, including those from regions like the Madras Presidency, followed similar critical trajectories. However, most of these publications could not sustain themselves over time. The reasons cited include the growing dominance of commercial Hindutva and the marginalization of subaltern groups from access to cultural and intellectual resources.

Subaltern studies challenged the notion of nationalism as either a unifying ideology for the masses or a deceptive construct used by dominant castes to preserve their power. At the heart of the subaltern intellectual tradition is the ethic of labour. This is evident in both Vak Dharma (oral traditions) and in Ambedkar’s thought. Experience, reason, and experimentation formed the core foundations of this tradition. The thesis points out that while thinkers like Tagore and Raja Ram Mohan Roy also demonstrated experiential modes of thinking, their frameworks largely ignored the labor and lives of subaltern communities.

Medieval Bhakti Movements

The thesis views the medieval Bhakti movements as a critique of cultural nationalism. Spanning from the 6th to the 19th century CE, these movements emerged across various regions and languages of India. Bhakti traditions had to confront the brutal repressions of the ruling powers. The thesis evaluates these movements as secular, pluralistic, and anti-orthodox expressions within India’s spiritual history. They brought together women, Dalits, and people engaged in devalued occupations in a liberatory and inclusive manner.

Bhakti movements in regions like Assam, Karnataka, and Maharashtra popularized local languages and challenged social injustices. Examples include Shankar Deva from Assam and Basavanna from Karnataka. Basavanna’s Vachana movement and the Mahanubhava tradition in Maharashtra promoted a divinity grounded in material life.

The thesis points to the contributions of women poets within Vachana literature and the legacy of this tradition, extending up to thinkers like M. M. Kalburgi. It also includes the traditions of the Siddhas and Sufis as part of the broader Bhakti movement. However, over time, the liberating spirit of Bhakti was gradually absorbed and diluted by Sanatan Brahmanism.

The Bhakti movements envisioned nations not as abstract concepts but as alternatives grounded in lived experience. Examples include the Pantharpuram of the washerwomen and Begumpura of Ravidas—imagined communities free of sorrow, taxation, and inequality. These were social visions where humans respected one another and labour was celebrated.

The thesis argues that Bhakti played a crucial role in sustaining India’s pluralistic and autonomous cultural identity.

Beginning in everyday life, the Bhakti movement initiated a comprehensive transformation across areas such as language, equality, gender harmony, caste rejection, and spirituality. It laid the foundational ground for later ideas of nationalism. However, Orientalist scholars and Indian historians alike failed to give the Bhakti movement the prominence it deserves in the narrative of India’s intellectual and social history.

Drawing on the perspectives of Prof. G Aloysius the researcher argues that subaltern struggles made possible new conceptions of citizenship, mass literacy, and social dynamism. These movements demonstrated that a reconstruction of society based on equality is only achievable by subverting the codes of respectability, the violence-based hierarchies, and the cultural authority embedded within India’s social structure.

The subaltern and avarna movements can be seen as liberationist ideologies that gained momentum in the 19th century and were gradually eclipsed by the early decades of the 20th century. The thesis critiques how these emancipatory impulses were co-opted and derailed by initiatives such as the Harijan upliftment and the ethos of seva (service), which were part of the Indian National Congress, Gandhian politics, and Hindu reformist projects.

According to the researcher, this appropriation attempted to suppress the radical potential and critical awareness embedded within Indian nationalism.

Epics and Puranas, the thesis notes, are also foundational texts that contributed to the devaluation of caste communities. Literary prowess was a key distinguishing feature of Brahmin priests, enabling their dominance. For historical analysis, Dharmananda Kosambi (Dharma Teertha) employs Buddhist philosophy. He argues that it was Buddhism that first unified India as a nation and led the country toward advancement in all spheres. Dharma Teertha elaborates on the achievements of Ashoka’s reign to support this claim.

Following the decline of Buddhist influence, Brahmin-centered regimes reasserted control; this, the thesis argues, became the historical framework adopted by Hindutva nationalists. These nationalists obscured the distinctions between Buddhists and Brahmins to construct a homogenized narrative of ancient India. Dharma Teertha recognizes the need to focus on Buddhist history, which had been deliberately marginalized. His writings also document how British colonial rulers maintained strategic alliances with temple authorities and how Sanatana conservatives infiltrated key centers of power.

Buddhist Conversion (1942) argues that Buddhist philosophy has no connection whatsoever with Brahmanical doctrines. The text discusses developments during the reigns of Ashoka and Kanishka. The author highlights that Siddha Nagarjuna played a major role in altering Buddhist thought and in the creation of a new priestly class, which marked a departure from the egalitarian spirit of early Buddhism. Although Buddhist culture experienced a strong resurgence during Harsha’s reign, this was accompanied by the continued codification of Brahmanical legal texts and aggressive efforts to uproot Buddhism.

Hiuen Tsang’s Journey to India (1947) is portrayed as a historically grounded text that adheres to factual accuracy while resisting distorted imaginations. According to the thesis, the kings who upheld Buddhist values regarded secularism as a guiding ideal for the state. The 7th century CE was a period of transformation and diversification within Buddhist philosophy. Hiuen Tsang firmly aligned himself with the Mahayana tradition during this time.

Conclusion

Ratheesh’s thesis can be seen as a pioneering contribution to subaltern aesthetics within Malayalam research. Its conclusions and insights lend strong academic legitimacy to India’s pluralistic and secular intellectual traditions. By revisiting the formation and evolution of cultural nationalism, the thesis systematically establishes the counter-currents that opposed it with analytical clarity.

It is within the broader context of cultural nationalism that formal Malayalam scholarship itself began to take shape. The dominant research methodologies in Malayalam studies historically reinforced these nationalist-cultural interests. The emergence of interdisciplinary, critical, and culturally grounded approaches in later phases of Malayalam research must therefore be evaluated about how they responded to cultural nationalism. It is important to ask to what extent Malayalam research has been able to generate fundamental ruptures in this regard.

This thesis demonstrates a critical engagement with both the historical construction and the declared content of cultural nationalism. Within the diverse and evolving methodological approaches in contemporary Malayalam scholarship, such counter-perspectives gain renewed relevance. Only through active and creative engagement with these perspectives can Malayalam research meaningfully reflect on its future.

Translated by Latha Karuthedath