Rethinking public finance in India through the lens of J C Kumarappa – Part II

Through this series of articles Prof. Jos Chathukulam argues that the public finance envisioned by J C Kumarappa needs to be seriously take into consideration by the modern-day public finance experts and economists in India. Rethinking public finance is required if India needs to become Viksit Bharat by 2047 and the most sustainable way to do it is to adopt the Gandhi-Kumarappa economic model.

The second part of this article discusses the opinions of public finance experts and Gandhian scholars on Kumarappa Model of Public Finance and looks into the Kumarappa Economy through the lens of Degrowth. It is followed by a discussion and conclusion.

Read Part One of the article

Part II: Public finance experts and gandhian scholars on kumarappa model of public finance

V M Govindu and Deepak Malaghan in Building a Creative Freedom: J C Kumarappa and His Economic Philosophy, argue that Kumarappa offered a foundational alternative to modern macroeconomics and Nehru model of public finance. They further argue that Kumarappa as a pioneer of ecological public finance, emphasizing local self-sufficiency and moral foundations of taxation and finance (Govindu and Malghan, 2005).

Mark Lindley in J C Kumarappa: Mahatma Gandhi’s Economist, presents a comprehensive account of how Kumarappa played an instrumental role in shaping Gandhian economic philosophy. Lindley argues that Kumarappa advocated public finance as a moral act, budgets as ethical duty (Dharma) rather than economic might (Lindley, 2007). Lindley further argues that Kumarappa’s approach contrasts with modern capitalist public finance systems, especially in areas like defence and military spending, land taxation and social welfare.

Zachariah in Developing India: An Intellectual and Social History, 1930-1950, argues that Kumarappa attempted an economic decolonization by incorporating village republics, cooperative living and decentralized public finance (Zachariah, 2005). Solomon Victus in his work Religion and Eco-Economics of J C Kumarappa argued that Kumarappa’s Christian background and Gandhian spiritual ethics shaped his views on economic justice, non-violence in taxation and environmental sustainability. Victus also points out that Kumarappa’s focus on eco-theology align with faith, ethics in public finance paradigm (Victus, 2018).

The Economy of Permanence, proposed by J.C. Kumarappa, concentrates on a natural order that supports the development of a society that coexists with nature, focusing on the use of renewable resources and sustainable methods (Chathukulam et al., 2018). Kumarappa’s Economy of Permanence and Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s Integral Humanism framework can be used for achieving integral development (Upadhyaya,1965), social order and a new Upanishad of life, thereby generating new horizons of social theorizing, social transformation and planetary realizations (Chathukulam et al., 2018, Chathukulam et al., 2021)

Part III- Kumarappa through the lens of degrowth perspective

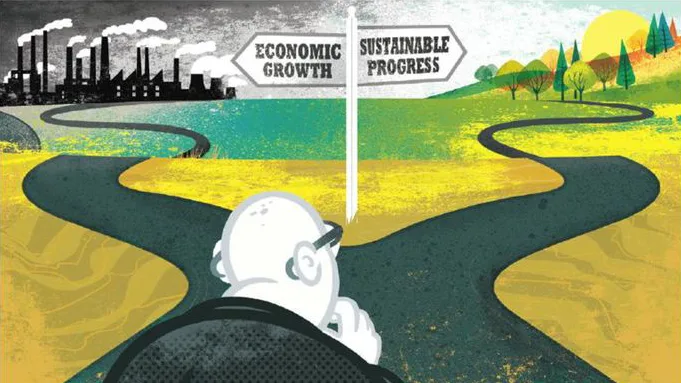

Parallels can be seen between Tim Jackson’s Prosperity Without Growth and Kumarappa’s Economy of Permanence as both rejects GDP as the sole indicator of progress and development (Kumarappa, 1931, Jackson, 2009). While Kumarappa critiques colonial exploitation and industrialism Jackson critiques consumer (Kerala Economy Vol.6 No.3 July – September 2025 ) capitalism and its ecological impact. Kumarappa draws from Gandhian principles of non-violence, Christian service ethics and village self-reliance. Jackson emphasizes social justice, environmental ethics and well -being economics and a Gandhi -Kumarappa influence strongly resonating in his ideological perspectives.

Jason Hickel’s Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World offers a powerful critique of capitalism and colonialism and proposes an economy grounded in ecological balance, justice and moral values. Kumarappa also discusses more or less these aspects in the backdrop of colonialism and mismanagement of public finance by the British in India.

Kohei Saito’s Slow Down: How Degrowth Communism can Save the Earth shows that both Saito and Kumarappa (Economy of Permanence) share similar ideas on ethical economics, moral economy as well as ecologically sustainable development. While Kumarappa argues colonial public finance is extraction of imperial growth, Saito connects capitalism’s origin and expansion to imperial extraction and exploitation. Kumarappa advocates for an Economy of Permanence based on village industries and non-violence, while Saito proposes degrowth communism, collective ownership, reduced working hours and eco-social balance (Saito, 2024).

Social embeddedness of economic life is a common theme in Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation (1944) and Kumarappa’s seminal works, particularly Public Finance and Our Poverty and Economy of Permanence. Ethics is also a common factor in Polanyi and Kumarappa, as in the case with social justice. In other words, Kumarappa’s Economy of Permanence resonates well with Polanyi’s vision of social re-embedding of the economy (Polanyi, 1944). Polanyi and Kumarappa advocated for sustainable development and human -centered economies. Kumarappa’s ideas are more relevant than ever in today’s world, particularly in the wake of the climate crisis and rural distress stemming from socio-economic inequalities (Bandhu, 2018). Kumarappa was a pioneer of ecological economics. Kumarappa’s ideas and thoughts are closely aligned with degrowth and sustainable development theories in today’s world.

The critiques of global economic systems and consumption patterns presented by Kohei Saito, Ulrich Brand, and Markus Wissen converge on the notion that the affluent lifestyles characteristic of the Global North are predicated upon the exploitation of natural resources and labor from the Global South. This understanding is central to Brand and Wissen’s (2021) concept of the “Imperial Mode of Living,” which posits that the resource-intensive and ecologically unsustainable lifestyles of people in the Global North are inextricably linked to the extraction of energy and natural resources from the Global South.

In a similar vein, Kumarappa’s work on Gandhian economics offers a prescient critique of Western-style development and consumption patterns. Kumarappa’s emphasis on decentralization, self-sufficiency, and environmental sustainability resonates with the critiques of Brand, Wissen, and Saito, highlighting the need for a more equitable and ( Kerala Economy Vol.6 No.3 July – September 2025 ) ecologically conscious approach to economic development. By examining the intersections between these thinkers’ ideas, we can better understand the complex relationships between global economic systems, consumption patterns, and ecological sustainability. This analysis underscores the importance of rethinking our assumptions about economic growth, development, and the natural world, and highlights the need for more nuanced and equitable approaches to addressing the challenges of the 21st century.

Though Kumarappa doesn’t use terms like ‘extractivism’ and neo-extractivism, his writings reflect the exploitation of natural resources for greed (Chathukulam and Joseph, 2024, Chathukulam and Joseph, 2023). Here is an excerpt from Kumarappa’s Why the Village Movement (1936): “Mines and quarries are the treasure trove of the people. Unlike the forests, these are likely to be exhausted by exploitation. Hence great care must be taken to make the best use of thorn. They represent potential employment for the people. When ores are sent out of the country, the heritage of the people of the land is being sold out. It is the birth right of the people to work on the ores and produce finished articles. Today, in India, most of the ores are being exported. We are, therefore, not only losing the opportunities of employment for the people but impoverishing the land. Minerals, like other raw materials, have to be worked into consumable articles and only after that can the commerce part of the transaction commence. Any Government that countenances of a foreign trade in the raw materials of a country is doing a disservice to the land,” (Kumarappa, 1936, p.111).

Alberto Acosta argues that extractivism was an instrumental mechanism for colonial and neo colonial plunder and appropriation. According to Accosta, “This extractivism which has appeared in different guises over time, was forged in the exploitation of the raw materials essential for the industrial development and prosperity of the Global North……………. Extractivism has been a constant in the economic, social and political life of many countries in the Global South,” (Acosta, 2013).

Kumarappa is also viewed as a Christian – Gandhian Socialist, who sought an economic model rooted in nature and justice- the Economy of Permanence, sustainable, decentralized and morally sounds (Moolakkattu, 2022). Gandhi, Kumarappa and E.F. Schumacher, adhere to the separation of the economy of permanence from economy of violence (Nair and Moolakkattu, 2017). Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful and Kumarappa’s Economy of Permanence, share common goals, including an ethical, sustainable and human-centered economy (Nair and Moolakkattu, 2017).

The 2011 Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel Report (WGEP), also known as the Gadgil report, envisions an inclusive, democratic and decentralized approach to environmental governance and this is in line with Gandhi and Kumarappa’s vision of village republics (Nair and Moolakkattu, 2017). While V K R V Rao appreciated the moral -ethical concern and rural focus of the ( Kerala Economy Vol.6 No.3 July – September 2025) Kumarappa-Gandhi economic paradigm, particularly in his work Gandhian Alternative to Western Socialism (1970), he expressed skepticism towards heavily decentralized Gandhian economics and its practicality (Rao, 1970). Though Rao has not explicitly criticized Kumarappa, Rao’s strong advocacy for industrial planning, public-sector growth and capital-intensive modernization contrasts with Kumarappa’s village – centric ethical economic framework. While Rao underscored that values and ethics should be integrated within economic realism, his fundamental support was for industrial and capital-based models, as is evident from Rao’s India’s National Income 1950-1980 and other prominent works.

Kumarappa’s economic paradigm emerged from the local realities and experiences of the people. This understanding helped him challenge the colonial and capitalist economic structures with the support of a Gandhian framework (Gireesan, 2018). Public finance experts in India should revisit the ideas propounded by Kumarappa to address the climate change crisis, rampant social and economic inequality and underdevelopment in rural areas (Gireesan, 2018). Kumarappa’s economy of permanence offers a moral and ecological foundation for public finance and policy making in the present-day times. Shivanand Shettar in his paper titled J C Kumarappa: The Educational and Cultural Ambassador of Gandhian Model of Development, describes Kumarappa as an ambassador of Gandhian economic model, stressing education and culture (Shettar, 2018).

J. Thomas, a celebrated economist in British India and Independent India, shares thematic similarities with Kumarappa’s vision on decentralized rural planning, public finance, cooperatives and focus on the rural poor (Thomas, 2021). John Moolakkattu, in his book titled J C Kumarappa, argues that while the contributions of Gandhi and E M S Namboodiripadu in decentralization, were duly acknowledged in Kerala’s People’ Plan Campaign (PPC), which began in the mid-90s to spearhead democratic decentralization, Kumarappa’s efforts in this realm especially in strengthening village economy was pushed to the oblivion (Moolakkattu, 2022). This is mainly because Kumarappa remains largely absent from the popular culture. While there are biopics and documentaries on the life and times of Gandhi, Nehru, Patel and Ambedkar, the same cannot be said about Kumarappa. He still remains the forgotten Gandhian economist. Meanwhile, A. M. Jose comments that Kumarappa’s ideas and themes have been discussed in Bollywood films like Lagaan (colonial taxation and rural resilience), Swades (decentralization, self-reliance), Peepli Live (criticizes apathy of modern economics to rural poor) and Jai Bhim (structural injustice and poverty – a core concern of Kumarappa).

Kumarappa’s contributions are ignored in the academic circles, particularly Gandhian studies and mainstream economic studies, within India and abroad. For instance, young professors with PhDs in economics, working in premier policy research and academic institutes in India, were found to be ignorant about Kumarappa and his economist. As part of National Education Policy (2020), Indian Knowledge System (IKS) is given due importance and Indian Economic Thought is major part of the curriculum and syllabi. The academic professionals in charge of designing core papers and curricula failed to incorporate Kumarappa and when asked about the reason for not incorporating Kumarappa, the academicians replied that they had not even heard about Kumarappa’s Economy of Permanence, let alone Kumarappa. Even in universities that offer Gandhian Studies, there is not even one core paper on Kumarappa, as in the case of Ambedkar University. It doesn’t stop with Kumarappa alone, books of renowned Gandhian scholars like Romesh K Diwan, Mark Lutz, Amlan Dutta, Mark Lindley, Narendar Pani, J.D Sethi, B.N. Ghosh, Amritananda Das also find no mention in the course curricula or the books recommended to students for further reading. Diwan and Lutz jointly published Essays in Gandhian Economics (1987), Diwan’s Gandhian Economics: Enoughness as Real Wealth (1979), J. D. Sethi’s Trusteeship: The Gandhian Alternative (1986) , Amlan Dutta’s The Gandhian Way (1986), Mark Lindley’s Gandhi on Health(2019), B. N. Ghosh’s Beyond Gandhian Economics: Towards a Creative Deconstruction (2013), Narendar Pani’s Inclusive Economics: Gandhian Method and Contemporary Policy (2001), Amritananda Das’s Foundation of Gandhian Economics (1979) are not mentioned in the recommended readings nor the core papers.

Gandhi himself overshadows Kumarappa’s contribution in Gandhian economics. Kumarappa is often treated as a footnote in Gandhian and economic studies. Mark Lindley, in the introductory chapter of his book titled J C Kumarappa: Gandhi’s Economist wrote: “Two experts advised me not to call Kumarappa “Gandhi’s Economist.” An economics professor in Kerala told me in 1988 that Kumarappa was “good man but not an economist,” whereas an American-trained economics professor active in Hungary and Turkey told me, after reading a draft of his book in 2003, that Kumarappa was too important an economic thinker to be tagged a mere Gandhian,” (Lindley, 2007). Kumarappa’s contribution to ethical economy is not treated as separate and specialized discipline; it is considered an appendage of Gandhian economics.

Discussion and conclusion

Despite its significance, public finance, particularly the quality of public expenditure, has largely been overlooked by policymakers and economists in India (Chathukulam, 2024, Karnam, 2022). At this juncture, Kumarappa offers an empirical understanding of historical trends and composition of public expenditure in India; the political economy of spending decisions and best practices that can guide India’s coursecorrection process (Chathukulam, 2024). Kumarappa is also credited with offering an empirical understanding of public finance or a ‘field view’ of the public finance scenario in India whereas public finance experts and policymakers of today are largely relying on secondary and tertiary inputs to formulate policies, theories and interpretations. As a result, most people handling public finance as a discipline and profession are out ( Kerala Economy Vol.6 No.3 July – September 2025) of touch with the ground realities as they interpret things through ‘textbook view’ rather than a ‘field view’. Gandhi-Kumarappa framework calls for civilizational reorientation – not just reformist adjustments to growth-centered economics (Nadkarni, 2018). An ecological, ethical and sustainable paradigm is what Kumarappa offers through his Economy of Permanence (Nadkarni, 2018).

Kumarappa’s moral economic development typology includes Parasitic Economy (Exploitative), Predatory Economy, Enterprise Economy, Gregarious Economy (like a honeybee colony dedicated to mutual welfare) and Seva Economy (service-oriented). The modern-day public finance, including global public finance, falls under the category of parasitic and predatory economy; in some aspects; it qualifies as enterprise economy. While Kumarappa has made incredible contribution towards strengthening the public finance mechanism in India, there are only a few takers. Even public finance experts who write extensively on the need to adopt alternative development have failed to incorporate the Gandhi- Kumarappa economic model as a viable model in reshaping the public finances (Ray, 2024). As the countries across the globe are in the race to achieve sustainable development goals by 2030, India can secure a far more edge over other countries if it can revisit the Gandhi-Kumarappa economic worldview.

While embracing the Gandhi-Kumarappa framework in its entirety may seem impossible, alternative models that are rooted in social solidarity economies can be adopted as a viable option in this regard. India needs economists and public finance experts who can see through the eyes of the poor and marginalized sections of society. As Kumarappa rightly points out in the Introduction of Public Finance and Our Poverty, “Indeed, when public finance is the handmaiden of public-spirited and farsighted statesmen, it could be the making of a powerful nation, but when mishandled, it could also be the ruination of a flourishing people. Like all other powerful instruments, this science is capable of being used for good, or ill, and therefore, it should be entrusted only to prove friends,” (Kumarappa, 1930).

The core thesis of Kumarappa’s Economy of Permanence, or Kumarappa’s theory of public finance, emerges from the wise Talisman of Mahatma Gandhi. According to Gandhi, “Recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man [woman] whom you may have seen, and ask yourself, if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to him [her]. Will he [she] gain anything by it? Will it restore him [her] to a control over his [her] own life and destiny? In other words, will it lead to swaraj [freedom] for the hungry and spiritually starving millions? Then you will find your doubts and yourself melt away,” (Pyarelal, 1958).

While Kumarappa did not use the term ‘extractivism’, he was talking about the colonial plunder in India as a form of economic extractivism. New forms of extractivism have emerged over the years but majority of the public finance experts and economists in India have not discussed extractivism policies inherent within the modern-day public finance. The concept of extractivism and neo-extractivism are often discussed without ( Kerala Economy Vol.6 No.3 July – September 2025) adequately considering their underlying political economy context, which includes power dynamics, economic structure, and institutional arrangements that shape the extraction and exploitation of natural resources. Meanwhile, leading research and policy institutes specializing in fiscal and social policy, such as the Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation (GIFT), Thiruvanthapuram, Kerala, have made significant strides in rethinking public finance to emerging development challenges. The GIFT recently conducted a three-day international conference titled ‘Rethinking Public Finance for Emerging Development Challenges’ from 19 – 21 March, 2025 and meaningful deliberations concerning the need to rethink public finance was discussed by public finance experts and scholars across India and beyond. These efforts offer promising avenues for reform and innovation of the domain of public finance in India.

P.P Pillai in his paper titled Relevance of Economic Ideas and Ideals of Mahatma Gandhi and JC Kumarappa in Today’s Context of Decentralization and Development, argues that “If Indians have at least an iota of love, regard and respect for Gandhi, because of whom only we enjoy ‘Democracy and Freedom’, now, it is our duty at this last phase of existence of humanity on this earth to discuss the relevance of development ideas of Gandhi and Kumarappa,” (Pillai, 2018).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor John S Moolakkattu, ICSSR Senior Fellow, School of International Relations & Politics, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, Kerala, India and Dr. A M Jose, Professor and Head, Amity School of Economics, Amity Business School, Amity University, Haryana, India for their comments on an earlier version of this article. However, the views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author, who alone bears full responsibility for any errors or omissions.

Endnotes

- The author has developed’AI-driven analysis within the framework of Transhumanism’ to Kumarappa’s philosophical and economic ideas on public finance on July 15, 2025. The aim is to provide insights into his likely position on GST, had he been alive to consider the issue. Kerala Economy Vol.6 No.3 July – September 2025

- A. M. Jose is the Professor and Head, Amity School of Economics, Amity Business School, Amity University, Haryana, India (Interviewed on July 17, 2025

- Extrativism refers to large scale extraction of natural resources, often driven by external economic interests with significant environmental and social impacts. The economy’s reliance on exporting raw materials driven by entrenched economic interests and rent -seeking behavior, perpetuates a pattern of limited value addition and unsustainable development (Acosta, 2013).

- Neo- extrativism is a newer form of extractivism characterized by state -led or state captured resource extraction, often with promises of more equitable and better environmental management. Empirical evidence suggests that the promises of development are often rhetorical, and the process is instead characterized by rent – seeking behavior, which undermines the potential benefits of policy initiatives (Acosta, 2013).

This paper was originally published in the July–September 2025 issue of Kerala Economy.