Denied Autonomy: Kerala’s Betrayal of Adivasi Rights

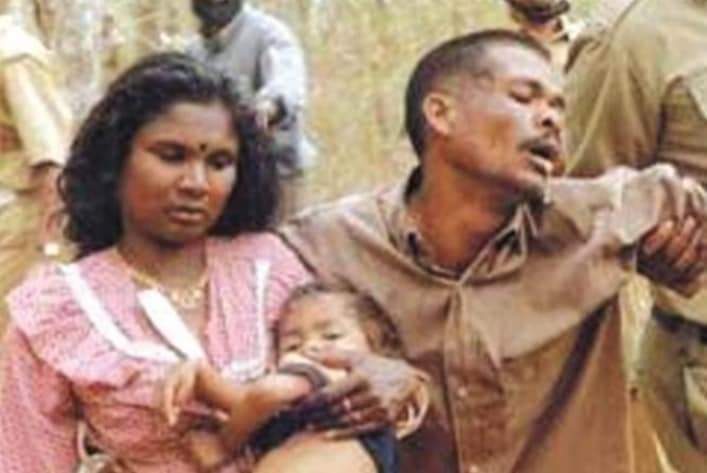

Successive Left and Right governments in Kerala have treated the tribal land issue as nothing more than a welfare matter. The broader public, too, has failed to grasp the Constitutional promise of self-governance for Adivasi communities. Key initiatives like the Muthanga package declared after the Nilpu Samaram (Standing Protest) remain unimplemented. The same holds true for implementation the PESA Act. In this concluding part of a long conversation, M. Geethanandan, convener of the Adivasi Gothra Mahasabha at the time of the Muthanga firing, reflects on the continued betrayal of tribal rights.

What was the Supreme Court’s ruling regarding the 1999 amendment to the Kerala Scheduled Tribes (Restriction on Transfer of Lands and Restoration of Alienated Lands) Act, 1975?

The verdict came in 2009. As I understand, Nallathambi Thera, who argued the case himself, was unable to make a strong case in the Supreme Court. The Court ruled that land should be returned in exchange for agricultural land, but it did not strike down the 1975 Act entirely.

The ruling effectively legalized encroachments of up to five acres made before 1986. It considered the principle of adverse possession that land held without dispute for 12 years could be legally claimed. However, this law does not address new encroachments or provide guidelines for them. That’s precisely the issue in Attappadi. A public interest litigation has alleged that 4,200 Adivasis lost their land, but no Adivasi has been made a party to the case. A tribal person can now approach the Supreme Court seeking a review.

After the 2009 verdict, the government took no action, essentially amounting to contempt of court. Though the Revenue Department issued an order to provide alternative land, it has yet to identify even a cent of land. During the 2001 Kudilketti Samaram (hut-building protest), there was an effort to take over Aralam Farm with the support of the Welfare of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes Minister M A Kuttappan’s office. Later, the Ministry of Environment was approached to allocate 30,000 acres of reserved forest. Though initially approved, no one knows which land was actually identified or transferred.

Meanwhile, the Tribal Rehabilitation and Development Mission (TRDM) was formed. In 2004, the matter came before the Central Empowered Committee (CEC) established under the Godavarman case. The Supreme Court, with Justice Balakrishnan as Chief Justice in 2009, ordered that land be allotted to Adivasis without delay. Even a Resettlement Commissioner was appointed, but nothing moved forward. That office was later shut down. So, despite identifying land for redistribution in 2009, no actual handover occurred. For example, Marianad in Wayanad district where the tribal protest is going on now is one of the areas identified.

What is the status of the Muthanga package announced after the 162-day Nilpu Samaram?

Currently, 3,000 acres are to be distributed under the Muthanga package. In Wayanad alone, 1,179 hectares have been identified. However, much of this land has been encroached upon by both the government and through illegal actions led by the Adivasi Kshema Smathi (AKS) formed by CPI(M) to counter Adivasi Gotramaha Sabha. Virtually no significant redistribution has occurred.

In 2010, the Revenue Department issued an illegal order handing over this land to non-Adivasi encroachers. DFO Dhanesh Kumar strongly opposed the Revenue Department’s order, noting that this land must be reserved for landless tribals.

To avoid contempt of court, a symbolic land transfer was held in Mannarkkad, where land was distributed to over 200 people in Attappadi. Eighty families were given land in Aralam, but most never moved there.

The Muthanga package is scattered and lies unimplemented. A master plan created under the package identified 52,000 landless tribals in Kerala and 25,000 in Wayanad alone. Those with less than one acre were considered landless. Additionally, a detailed survey by KILA (Kerala Institute of Local Administration), costing ₹3.5 crore, remains unused by the government.

One major outcome of the Nilpu Samaram was the decision to implement the PESA Act. Protesters demanded the recognition of social and community forest rights. The significance of PESA villages was acknowledged at that time. Instead of gram sabhas, tribal villages were considered the appropriate local governance units.

Tribal regions in Wayanad, parts of Nilambur, Aralam Farm panchayat, and three panchayats in the Attappadi block were brought under Scheduled Areas status, approved by the relevant ministry. A technical committee was formed in 2017 to map these areas. The Administrative Reforms Commission led by V.S. Achuthanandan accepted our submission, and KILA proposed a detailed implementation plan. Today, the government can easily implement PESA—if it truly wishes to.

Yet in 2020, forest rights were canceled in four districts. What happened?

Yes, in 2020, forest rights in Idukki, Kottayam, Pathanamthitta, and Ernakulam were revoked. This decision effectively opened up forest land to market transactions under the guise of private ownership. The Pinarayi Vijayan government supported this move, claiming it served the interests of the Malayara tribal community.

But what such communities truly need are alternative institutional systems like tribal banks to meet financial needs without surrendering their rights. Even the state cannot reclaim land once forest rights are granted. Here, it’s important to understand the difference between the standard three-tier panchayat system and the PESA framework, which offers self-rule for Adivasi communities.

How many of those who participated in the Muthanga struggle actually received land?

The distribution has been patchy. More than 800 families were involved in the struggle. Initially, 650 people applied. The government issued an order saying that 447 of them didn’t own even a cent of land and then added that it would revise the list.

In the list they themselves published, the average landholding was just five cents. It was a clear attempt to disqualify people using technicalities. Later, the Scheduled Castes Department submitted a list of 221 people. Eventually, a pattayamela (title deed ceremony) was held in Wayanad for 283 people.

In the Vellari Hills in Wayanad, 110 families were given one acre each. This land was relatively good. But in places like Valad and Thondarnadu, land was allocated on hilly, uninhabitable terrain.

There seems to be a widespread lack of awareness in Kerala about the constitutional right of tribals to self-governance. What is your view?

Indeed, after the 1980s, several major protest movements emerged from marginalized communities in Kerala—fisherfolk, plantation workers, and tribals. These were groups historically alienated by colonial rule and largely excluded from the much-lauded Kerala development model. Among them, tribal communities have responded with a distinctly political approach. Yet, there has been little serious academic inquiry into these movements.

There is no broad public understanding or recognition of the cultural, social, and political rights of tribals as a minority. This ignorance is a legacy of the dominant socialist and communist frameworks in Kerala, where social hierarchies still persist. Tribals were even left out during the much celebrated land reforms. Many so-called liberals still view tribals as subjects to be uplifted, rather than as communities with their own political agency. This paternalistic attitude prevents them from accepting the legitimacy of tribal self-governance.

The issue of nature conservation reflects a similar bias. Conservation efforts here are often rooted in colonial frameworks. Even individuals like K. Panur, who was genuinely sympathetic to tribal causes, carried this mindset. The Attappady Hill Area Development Society (AHADS) functioned under this very framework. While Kerala often celebrates its Renaissance values, these rarely extend to its tribal population. In fact, Kerala society sees tribals much like colonial Europe viewed Black communities as backward and expendable. An upper-caste consciousness underpins much of this thinking.

Even Kerala’s land reforms avoided disrupting the plantation economy. The reforms were mostly limited to regulating the landlord-tenant relationship. Those who benefited from this limited reform later emerged as the new ruling class.

Environmentalists in Kerala, too, often oppose tribal rights to self-governance and forest land. While they champion conservation, they have no objection when settlers are granted land ownership. There’s no accountability for the blunders committed in the name of conservation. Ironically, those who once advocated tiger protection now support shooting them. We see the same contradictions in debates around buffer zones that decisions are made without credible data or studies.

This same limitation was evident in the Plachimada agitation. The issue wasn’t framed as one of decentralization or community control over natural resources. Instead, it was reduced to a discussion about compensation. The real question whether monopolies have the right to control common resources was never asked. There should have been a push to recognize a community’s right over water drawn by an individual or company. That conversation never happened. Kerala desperately needs platforms where marginalized voices can be heard, and traditional community rights restored.

Even the National Human Rights Commission acknowledged the brutality inflicted on tribals during and after the Muthanga police action. Yet, both academia and the public have largely ignored the incident. Why? Because the tribals protested with a clear political agenda. That made the movement inconvenient to their interest. To this day, there are no serious studies on the causes and consequences of the Muthanga struggle. Kerala’s dominant middle-class consciousness refuses to understand or engage with the distinct cultural and political identity of tribal and Dalit communities.

Has there been any shift in the government’s approach to the tribal land issue after Muthanga?

Unfortunately, no. Both Left and Right governments in Kerala have consistently viewed the tribal land issue as a matter of welfare, never as a constitutional right. This remains the case even today.

Kerala’s land reforms in the 1970s, which aimed to end feudalism, made no space for tribal land rights. The state continues to treat tribal claims through the lens of surplus land distribution, not justice or restitution. Ironically, tribals as one of the most excluded groups are also left out of the state’s ‘development’ success story.

For tribal communities, land is not just property. It is a foundation for their culture, identity, and survival. It is deeply linked to food security, health, self-sufficiency, and social protection.

Kerala’s much-celebrated renaissance and scientific consciousness often label tribal cultures as backward. Has this mindset contributed to their marginalization?

Absolutely. Kerala’s public consciousness is far from inclusive. In fact, it often refuses to acknowledge the very existence of tribal worldviews. There is also an underlying upper-caste mindset that many don’t even recognize in themselves. For instance, the POCSO Act has been disproportionately used against tribals.

One of the major demands of the Muthanga protest was the right to self-rule under the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution, wasn’t it?

Yes. But both the state and the public remain unwilling to acknowledge tribal autonomy or the potential of the Fifth Schedule. These topics are absent from mainstream discourse. The constitutional safeguards for Adivasis and the repeated violations of those protections are not treated as serious issues in Kerala.

Tribals in Kerala have been raising this issue seriously since the 1990s, right?

That’s correct. The 1990s marked a turning point when landlessness became a crisis. In fact, the issue was raised even earlier in the 1980s. But it was in the early 1990s that tribals themselves began articulating their demands in a collective, organized manner.

Several factors contributed to this. Tribal labor was exploited heavily in plantation areas. Then, with globalization, many of those plantations shut down, and unemployment among tribals skyrocketed. At the same time, the public distribution system (PDS) was poorly implemented in tribal areas. By the mid 1990s, hunger, poverty, and deaths became widespread.

The media occasionally reported on these “unknown deaths” a euphemism for starvation. Problems like malnutrition and sickle cell anemia were mentioned, but often without deeper inquiry. During monsoons, stories about tribal suffering became a seasonal media feature. By the late 1990s, the impact of globalization worsened. Small farmers were under pressure, suicides increased, and work in plantations including those run by the Plantation Corporation dried up.

Wasn’t it also the socio-political context of the 1970s that prompted the central government to introduce land reforms and laws protecting tribal land?

Absolutely. The 1970s were marked by several intense struggles across India. On one hand were the farmers’ movements, and on the other, the Khalistan movement. There were also agitations led by Sharad Joshi in Maharashtra, Narayana Swamy in Tamil Nadu, and the radical Left including Naxalite uprisings challenging feudal structures. Movements like the Arkodu land struggle in Tamil Nadu, the Dalit Panther movement in Maharashtra, and the JP Movement shook the political foundations of the country.

It was against this backdrop that Indira Gandhi instructed state governments to address the tribal land issue seriously. Progressive reforms such as bank nationalization were already underway. Many civil servants of the time still held Nehruvian socialist ideals and bureaucrats like Dr. B.D. Sharma and the recently deceased P.S. Krishnan played key roles in shaping tribal policy. It was in this context that the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 was introduced. Earlier, only the Civil Rights Act existed.

The Tribal Sub-Plan (TSP) emerged from the evaluations of the Fifth Five-Year Plan, based on the understanding that the root of many social conflicts lay in the absence of economic and social justice for marginalized communities. Though The Dhebar Commission Report raised serious concerns, it was ignored for years due to its opposition to scheduling certain tribes.

Before the launch of the Integrated Tribal Development Programme (ITDP), there was the Modified Area Development Agency (MADA) initiative. Legislative measures such as the Bonded Labour Abolition Act and the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013 were also outcomes of this period’s political consciousness.

Hasn’t there also been a growing global awareness of tribal rights and ways of life?

Yes, very much so. Global institutions like the United Nations and the International Labour Organization (ILO) have significantly contributed to deeper discussions on indigenous rights. In 1993, the UN declared that the decade beginning in 1995 would be observed as the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. This spurred efforts worldwide, with many international and national voluntary organizations stepping in to protect tribal rights.

These developments had ripple effects in Kerala as well. Solidarity movements began gaining traction. A significant initiative was the South Indian Tribal Conference, organized by several voluntary groups. It helped coordinate tribal movements across Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka. The conference also sparked discussions on community autonomy and tribal self-governance. Activists like C. R. Bijoy played a key role in these efforts.

What has happened since Muthanga struggle?

The Muthanga struggle has largely been ignored by academia, primarily because it was a tribal-led political protest. It challenged not only the government but the broader development paradigm in Kerala. As a result, no substantial academic study has yet been published on the Muthanga uprising. The media, too, framed it as an extremist protest, conveniently overlooking its constitutional and political demands.

After the Muthanga incident, T. Madhava Menon was appointed chairman of the rehabilitation mission, but he too refused to accept the legitimacy of the PESA Act. Even K. Panur, who once brought attention to the exploitation of tribal areas, shared this reluctance. P.R.G. Mathur, a leading researcher on tribal life, maintained that land should be provided to tribals only under state ownership or as public land reflecting a deeply paternalistic mindset.

Meanwhile, the public remains largely indifferent to the ongoing violations of constitutional safeguards provided to tribal communities.

But didn’t the central government attempt to correct this with the Forest Rights Act?

Yes. In 2006, the central government enacted the Forest Rights Act (FRA) with the explicit intention of addressing the “historical injustice” inflicted upon India’s tribal and forest-dwelling communities. Yet, Kerala has failed to implement the law meaningfully. The state continues to treat tribal demands as welfare issues, not as rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

Designating areas with significant tribal populations as Scheduled Areas, and granting individual rights, community rights, resource rights, and the right to determine the course of development are all constitutional mandates. Tribals are also constitutionally entitled to cultivable land for their livelihood and cultural survival.

The struggle for these rights will continue. Unemployment and poverty among tribal communities are worsening by the day. It is imperative that we move away from viewing land distribution to tribals as mere charity or welfare, and recognize it as a fundamental issue of justice, autonomy, and survival.

(Interview ends)