Inequality in India: Living in a Time of Plenty and Deprivation

We are living in an age of obscene inequality. A world that produces unimaginable wealth denies even basic dignity to millions. While a tiny elite hoards income, land, and power, the majority are pushed into insecurity and silence. This article reads the World Inequality Report 2026 against the lived realities of India to expose how inequality is manufactured and why resisting it is no longer optional.

(An Analysis Based on the World Inequality Report 2026)

Economic inequality has become one of the most defining features of our times. Never before has the world produced so much wealth, and never before has that wealth been shared so unequally. The World Inequality Report 2026 reminds us of this uncomfortable truth: while global income and wealth have risen sharply, the benefits of this growth have flowed overwhelmingly to a small minority. This is not a contradiction of nature; it is the result of an economic system founded on exclusion, exploitation, and injustice. India stands out as one of the most unequal countries in this global landscape, not because it is poor, but because its wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few.

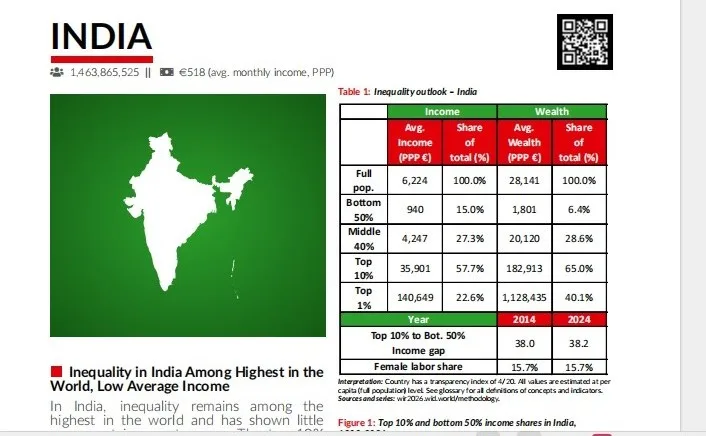

According to the India-specific data in the report (page 173), the richest 10% of Indians take nearly 58% of the country’s total income, while the bottom 50% are left with just 15%. In simpler terms, half of India lives on crumbs, while a small elite feasts on more than half the national income.

The picture becomes even uglier when we look at wealth. The top 10% owns around 65% of all wealth in India, and the top 1% alone controls about 40%. Meanwhile, the bottom half of the population owns barely anything worth calling security. For millions of Indians, one illness, one job loss, or one climate disaster is enough to push them into permanent debt and desperation.

Growth Without Justice

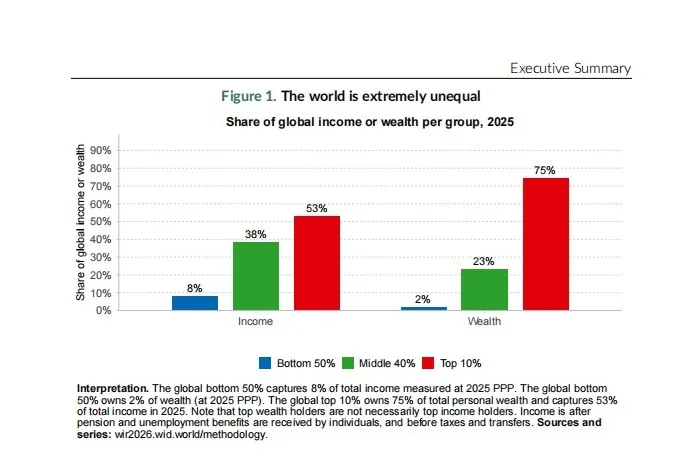

The richest 10% of the world’s population earn more income than the remaining 90% combined, while the poorest half of humanity survives on less than 10% of total global income. Wealth inequality is even more obscene: a microscopic elite controls resources that entire nations can only dream of. This is not progress. This is organised plunder.

India is often celebrated as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. High GDP growth rates, a booming stock market, glittering infrastructure projects, and the rapid rise of billionaires are presented as symbols of national success. But the World Inequality Report urges us to ask a deeper question: growth for whom?

According to the report, a tiny elite at the top captures a disproportionately large share of India’s income and wealth, while the majority struggles to secure basic necessities. The contrast is stark: on one side are luxury homes, private jets, and offshore investments; on the other, insecure jobs, stagnant wages, indebted farmers, informal workers without social security, and millions surviving on meagre daily incomes.

This is not an accident or a temporary imbalance. The report makes it clear that inequality in India is structural and persistent, shaped by policy choices, historical hierarchies, and the direction of economic development.

The Concentration of Wealth

One of the most striking findings of the World Inequality Report 2026 is the extreme concentration of wealth at the top of Indian society. A very small fraction of the population owns a massive share of national wealth, while the bottom half owns almost nothing in comparison.

For ordinary people, wealth is not an abstract concept. It means land, a house, savings, gold, livestock, or a small business—assets that provide security during illness, unemployment, or old age. When wealth is concentrated, security itself becomes unequal. The rich can withstand crises; the poor fall deeper into debt and precarity.

Inequality and the World of Work

India’s inequality cannot be understood without examining its labour structure. The report highlights how a large majority of Indian workers remain trapped in informal, low-paid, and insecure employment. Regular, well-paid jobs with social protection are available only to a small minority.

Despite economic growth, real wage growth for ordinary workers has been slow and uneven. Meanwhile, profits, executive salaries, and returns on capital have surged. This growing gap between labour income and capital income is a central driver of inequality.

For Dalits, Adivasis, women, migrant workers, and religious minorities, the situation is even more precarious. They are over-represented in the most dangerous, undervalued, and unstable forms of work—construction, sanitation, domestic labour, plantations, and the informal service sector. Economic inequality in India, therefore, is inseparable from caste, gender, and social discrimination. The market reproduces old hierarchies under the language of efficiency and growth.

Climate Crisis and Economic Inequality

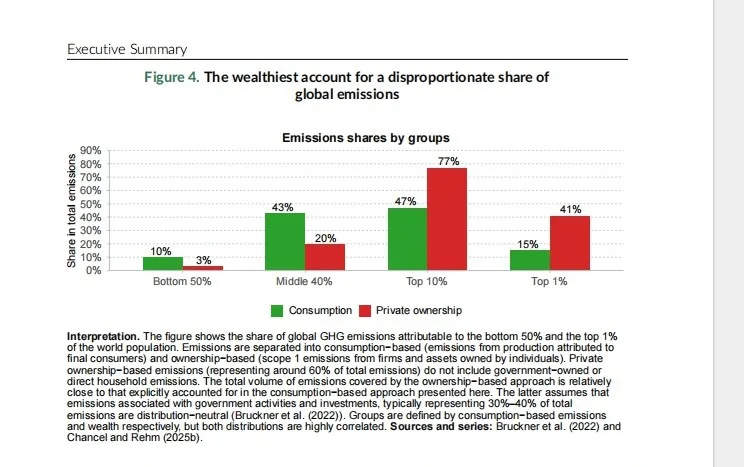

The World Inequality Report 2026 tears apart the comforting lie that climate change is a crisis created equally by all. It shows that the climate catastrophe is driven overwhelmingly by the rich, while its punishments are imposed on the poor. In fact, the top 10% of the global population are responsible for about 77% of carbon emissions linked to private capital ownership, while the poorest half of people contribute only around 3% of these emissions. The wealthiest 1% alone account for 41% of private capital ownership emissions, almost double the amount of the entire bottom 90% combined (page 12).

Because the 10% owns the corporations, industries, and financial assets that plunder nature for profit. In contrast, the poorest half of humanity including peasants, workers, Adivasis, fisherfolk, slum dwellers contribute almost nothing to this destruction, yet they are the ones whose lives are torn apart by floods, droughts, heatwaves, and crop failures. Climate change thus becomes a new weapon of inequality: the rich insulate themselves with money, technology, and political power, while the poor are left exposed to hunger, displacement, and death. This is not an environmental accident but a political crime. To fight climate change without confronting economic inequality is to protect the polluters and abandon the victims. Climate justice, the report makes unmistakably clear, is impossible without dismantling the concentration of wealth and power that fuels both ecological destruction and human misery.

Caste, Inequality, and Historical Injustice

The World Inequality Report does not directly measure caste, but the Indian context makes one thing clear: economic inequality is deeply entangled with caste hierarchy. Historical exclusion from land, education, and dignified work has left Dalit and Adivasi communities with far fewer assets and opportunities.

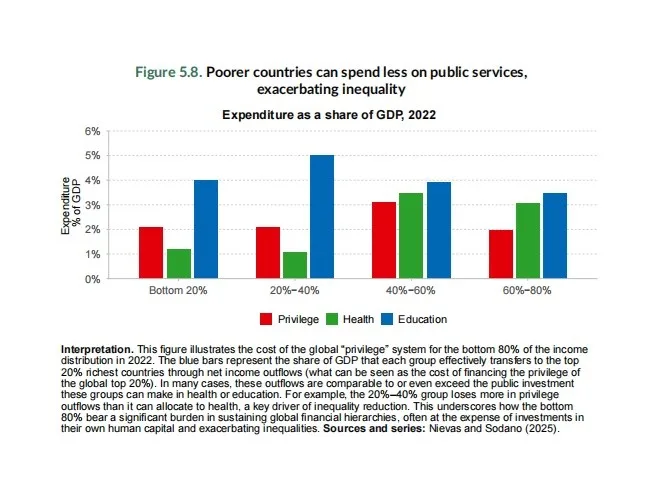

Privatisation, weakening of labour protections, and the retreat of the state from welfare have further worsened these inequalities. When public education and healthcare decline, those with wealth buy private services, while the poor are left behind. Inequality thus reproduces itself across generations.

In this sense, inequality is not merely an economic problem; it is a democratic and moral crisis. A society that allows a few to accumulate enormous wealth while many lack basic dignity cannot claim to be just.

Inequality and Democracy

The report also raises a crucial warning: extreme inequality threatens democracy itself. When wealth is concentrated, political power follows. The rich influence policy through lobbying, corporate control of media, and close ties with the state. The voices of workers, farmers, and marginalised communities are increasingly sidelined.

In India, this is visible in policies that favour big corporations, dilute labour laws and implementation of labour codes, weaken environmental regulations, and suppress protests. Inequality thus becomes self-reinforcing: economic power shapes political decisions, which in turn deepen economic inequality.

Extreme inequality does not remain confined to the economy. It seeps into politics, institutions, and everyday life. When wealth concentrates, political power follows money. Policies are written to please corporations, not citizens.

Gender and Invisible Inequality

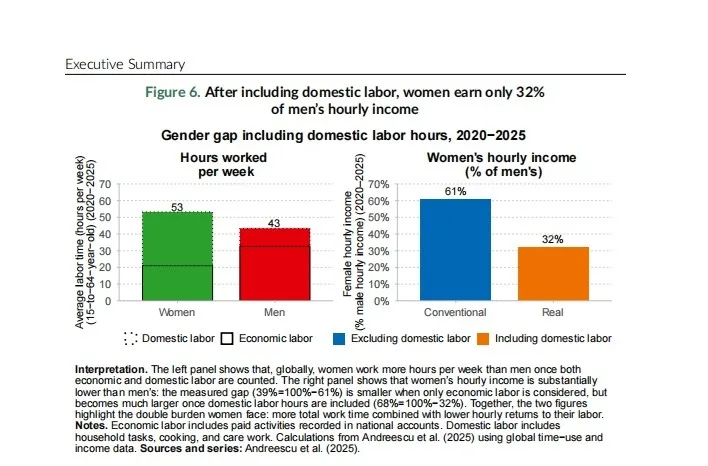

Another critical dimension highlighted indirectly by the report is gender inequality. Women in India earn less, own fewer assets, and perform a disproportionate share of unpaid care work. This unpaid labour such as cooking, cleaning, caregiving remains invisible in national income calculations but is essential to the functioning of the economy. Without recognising and redistributing this burden, economic growth will continue to rest on the exploitation of women’s labour.

The World Inequality Report shows that women’s participation in income-earning work in India remains extremely low, with little improvement over the past decade. Yet women work longer hours than men when unpaid labour such as are, cooking, cleaning is counted. This unpaid labour subsidises both the state and the market. It keeps households afloat while remaining invisible in economic calculations. A system that depends on invisible female labour while denying women economic power is not just unequal, it is unjust.

The Illusion of Trickle-Down

A key message of the World Inequality Report 2026 is the failure of the “trickle-down” model. The idea that wealth accumulated at the top will eventually benefit everyone has not materialised. Instead, inequality has widened even during periods of rapid growth. India’s experience confirms this clearly. The rise in billionaires has not eliminated hunger, unemployment, or agrarian distress. Growth without redistribution has produced islands of prosperity in a sea of deprivation.

The Way Forward: Rethinking Development

The report does not merely diagnose the problem; it points towards solutions. Reducing inequality is not impossible as it is a matter of political will and social struggle.

Some key directions for change include:

1. Progressive Taxation

India’s tax system must be made more progressive. Wealth, inheritance, and high incomes should be taxed fairly, while indirect taxes that burden the poor should be reduced. Tax justice is essential for funding public welfare.

2. Strengthening Public Services

Universal access to quality education, healthcare, housing, and social security is the most effective way to reduce inequality. Public investment must prioritise people over corporate profits.

3. Dignity of Labour

Minimum wages, job security, and labour rights must be strengthened, not diluted. Informal workers need legal protection and social security.

4. Addressing Historical Injustice

Redistribution cannot ignore caste and gender. Land reforms, affirmative action, and targeted welfare for marginalised communities remain crucial.

5. Democratising the Economy

Cooperatives, commons, local economies, and community-controlled resources offer alternatives to corporate domination. Economic democracy must accompany political democracy.

At a time when inequality is normalised and even celebrated, resisting it becomes an act of courage. The struggle for equality is inseparable from the struggle for dignity, democracy, and justice. As the World Inequality Report reminds us, another future is possible but only if people organise, question power, and reclaim the idea that the economy must serve society, not the other way around.

The images are sourced from the World Inequality Report 2026.

Featured Image Courtesy: Centre for Development Studies and Practice