Annihilation Deferred: Democracy’s Compromise with Caste

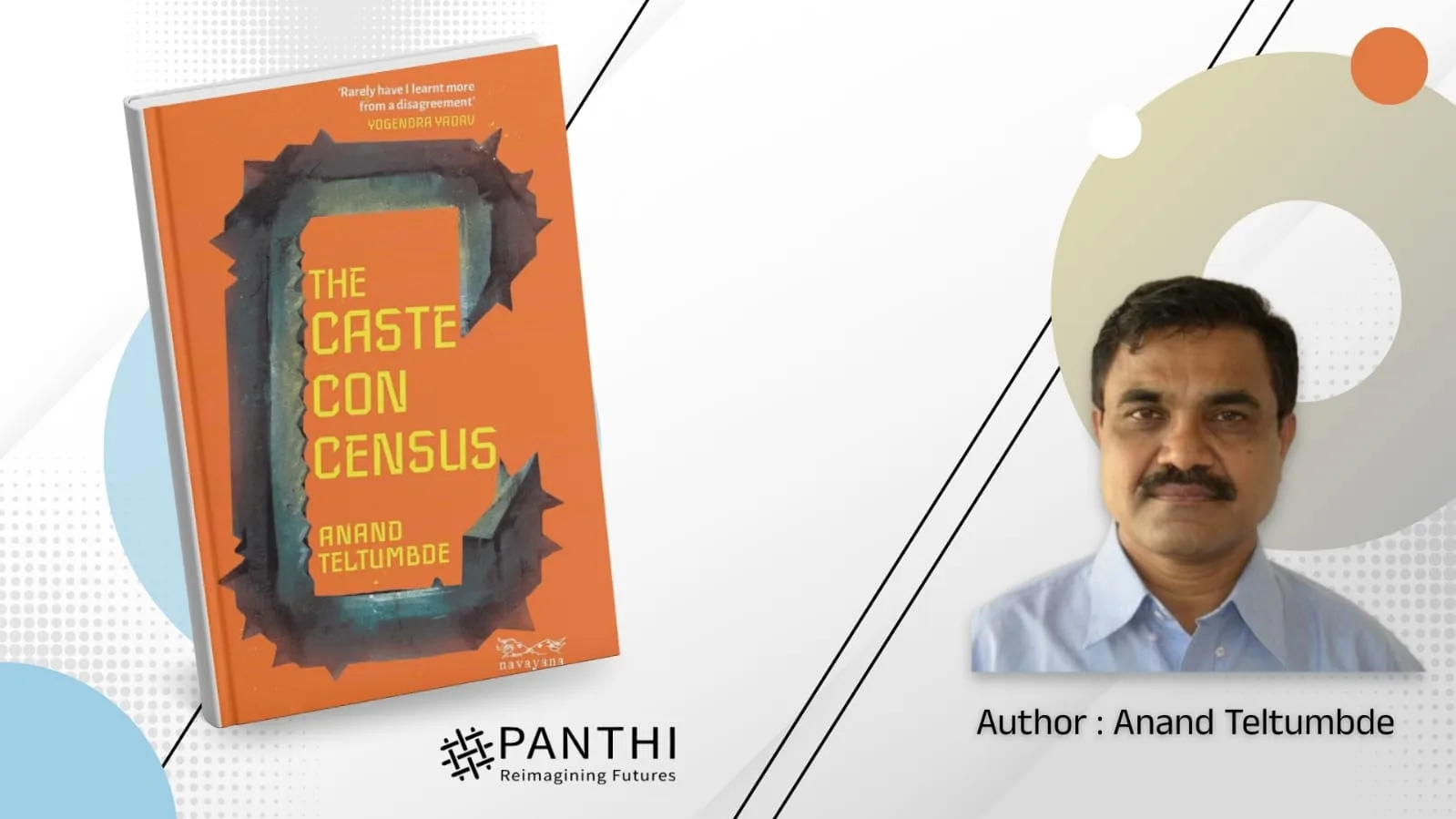

In this first part of the interview, Anand Teltumbde revisits the historical and political foundations of caste, challenging reductionist explanations that locate it solely in Brahminism. Drawing on his recent book, The Caste Con Census, he examines caste as a dynamic social formation shaped by state power, political economy, colonial modernity, and democratic institutions, offering a rigorous framework to rethink both anti-caste politics and Indian democracy itself.

Anand Teltumbde is an Indian scholar, writer, and activist known for his incisive critique of caste, capitalism, and Indian democracy, rooted in Ambedkarite and Marxist thought.

Part One

In the chapter “The Seeds of Jati” of your book Caste Con Census, you argue that Brahminism alone cannot explain the origins of caste. That caste must be understood as a political and social formation rooted in specific local contexts. How important is this non-reductionist understanding for addressing caste in contemporary India? (p. 24)

The non-reductionist understanding is absolutely crucial—without it, any contemporary engagement with caste is bound to be shallow and politically ineffective. If caste is explained solely as an ideological imposition of Brahminism, it appears as a timeless religious pathology, which leads either to moral denunciation or symbolic reform. Both fail. What The Seeds of Jati insists on is that caste emerged as a historical social formation, shaped by tribal incorporation, agrarian expansion, local political economies, state formation, and struggles over surplus and status. Brahminism did not create caste out of thin air; it provided a language of legitimation for hierarchies that were already taking shape through material and political processes.

This matters enormously today because caste in contemporary India does not operate only—or even primarily—through ritual ideology. It is embedded in land relations, labour markets, urban segregation, education, marriage networks, and state institutions. A reductionist view blinds us to how dominant non-Brahmin castes exercise power, how Dalit oppression is reproduced through markets and bureaucracy, and how caste mutates under capitalism. It also allows dominant groups to disown responsibility by blaming an abstract “Brahminism” while continuing caste practices in everyday life.

Politically, a contextual and relational understanding shifts the terrain of anti-caste struggle. It shows why annihilating caste cannot be achieved by cultural reform alone, nor by targeting one community as the sole bearer of caste ideology. It requires structural interventions—redistribution of land and capital, democratization of education, transformation of state practices, and reorganization of labour and representation. In short, seeing caste as a historically produced social formation allows us to confront it where it actually operates today, rather than where it is easiest to condemn it.

You note that Buddhism spread largely among merchant and artisan groups and often accommodated, rather than dismantled, existing hierarchies. Similarly, Bhakti and Sufi traditions created symbolic spaces of inclusion without fundamentally transforming social relations. Are you suggesting that Śramaṇa traditions, including Jainism, and later Bhakti movements did not pursue or could not achieve the annihilation of caste? (p. 24)

Yes—both historically and structurally, they did not, and in most cases could not, achieve the annihilation of caste. This is not a moral judgment on these traditions but a sociological assessment of their limits, which has been a fact of history.

Śramaṇa traditions such as Buddhism and Jainism arose as critiques of Brahmanical ritualism and sacrificial authority, not as projects for reorganizing social power. Their primary ethical thrust was individual salvation—nirvāṇa or mokṣa—pursued through renunciation, monastic discipline, or strict ethical codes. As a result, they largely bypassed the question of how everyday social relations—land control, labour, kinship, and political authority—were to be transformed. Where Buddhism spread beyond monastic circles, particularly among merchants and artisans, it often accommodated existing hierarchies to secure patronage and stability. Caste was neither central to its critique nor systematically targeted for dismantling.

The same structural limitation applies, in a different register, to Bhakti and Sufi traditions. They powerfully challenged Brahmanical exclusivity at the level of devotion and spiritual access, creating symbolic and affective spaces where caste hierarchies could be temporarily suspended. But these were largely ethical or devotional egalitarianisms, not programmes of social reconstruction. They did not seek to reorganize property relations, village power structures, or endogamous kinship systems—the institutional foundations of caste. Consequently, caste survived quite comfortably outside the devotional moment.

What this suggests is not that these traditions lacked radical intent, but that their mode of critique was fundamentally non-political in the structural sense. They contested authority in the realm of belief and practice, not in the organization of society. The annihilation of caste requires precisely what these movements did not—and perhaps could not—provide: a conscious, sustained project to transform social institutions, redistribute power, and dismantle inherited hierarchies. In that sense, their historical role was critical and often emancipatory at the level of consciousness, but insufficient at the level where caste actually reproduces itself.

You write that Muslim rulers, focused on consolidating power over a rigorously hierarchical society, did not attempt to dismantle caste structures, and at times even legitimised Brahminical social order within Indo-Islamic governance. Does this indicate that caste hierarchy historically functioned as a mechanism of political stability and control?

Yes. Historically, caste hierarchy functioned as a ready-made infrastructure of political stability and social control, and that is precisely why it was rarely dismantled by ruling powers—including Muslim rulers—despite their radically different religious worldview.

When Indo-Islamic regimes established authority over the subcontinent, they encountered a society already organised through dense, localised hierarchies of caste, lineage, and customary obligation. Rather than attempting to uproot this structure—which would have required massive coercive capacity and risked constant rebellion—most rulers pragmatically governed through it. Village elites, dominant castes, and Brahmins were retained as intermediaries for revenue extraction, legal arbitration, and social discipline. In this sense, caste was not merely tolerated; it was operationalised as a mechanism that translated imperial authority into everyday governance.

This also explains why Brahminical norms often received formal recognition under Indo-Islamic rule—through grants, temple endowments, or the validation of customary law. Such acts were not endorsements of caste ideology as theology, but acknowledgements of its utility. Caste provided predictability: fixed occupations, stable labour supplies, clear lines of authority, and inherited social obedience. For a state primarily concerned with revenue, order, and military power, this was an asset, not a liability.

The broader implication is analytically important. Caste survived not because it was uncontested or universally believed in, but because it was politically functional. It disciplined society from below, reducing the need for constant state intervention. This is why caste persisted across regimes—Hindu, Muslim, and later colonial—and why its annihilation has always required more than moral critique or religious reform. It demands a direct confrontation with the political economy and administrative logics that have repeatedly found caste to be an efficient instrument of rule.

You argue that colonial rule disrupted the dynamic nature of caste by formalising it through religious laws, censuses, and bureaucratic classifications (p. 41). Do you think that without this colonial intervention, caste might have evolved differently or even weakened in modern India?

Yes—colonial intervention fundamentally altered the trajectory of caste, and without it, caste would almost certainly have evolved differently. Whether it would have weakened is an open question, but it would not have assumed the rigid, pan-Indian, and administratively frozen form that defines modern caste.

Pre-colonial caste was hierarchical and oppressive, but it was also locally contingent, negotiable, and embedded in shifting political economies. Jatis rose and fell with changes in land control, military service, state patronage, and occupational reorganisation. Mobility—limited, uneven, and often violent—was nonetheless real. What colonial rule did was to arrest this fluidity by converting caste into a fixed identity category, legible to the modern state.

Through the census, ethnography, codified “religious” law, and administrative manuals, the colonial state transformed caste from a lived social relation into a bureaucratic fact. In the process, Brahmanical textual norms were elevated as authoritative descriptions of Indian society, marginal customs were erased, and caste boundaries were hardened across regions. Once attached to law, statistics, and governance, caste acquired a permanence it had never previously possessed. It ceased to be merely social; it became juridical.

This has long-term consequences. Modern Indian caste is not simply a survival of tradition; it is a product of modernity itself. Colonial governance universalised caste identity, synchronised hierarchies across space, and embedded them in institutions that outlived colonial rule—education, administration, and representative politics. Without this intervention, caste would still have persisted, but its forms would likely have been more fragmented, contested, and responsive to economic change. Under the onslaughts of modernity, there was a possibility of such castes weakening as they happened in Korea.

The irony is that colonialism did not invent caste oppression, but it decisively modernised it. By freezing caste into an all-India classificatory grid, it laid the groundwork for both contemporary caste discrimination and caste-based political mobilisation. Any serious analysis of caste today must therefore confront not only ancient hierarchies, but the colonial processes that re-engineered them into the durable structures we now confront. Post-colonial times they were further politicised and were transformed into what I called ‘constitutional castes’.

Many post-independence anti-caste narratives assume that colonial modernity helped dismantle traditional hierarchies. Yet Ambedkar remained sharply critical of colonialism’s failure to challenge caste at its structural core. How do you assess this contradiction in contemporary anti-caste discourse?

This contradiction sits at the heart of contemporary anti-caste discourse, and it reflects a persistent confusion between social mobility under colonial rule and structural transformation of caste. Many post-independence narratives mistake limited openings created by colonial modernity—education, law courts, urban employment, missionary activity—for a dismantling of caste itself. Ambedkar never made this mistake, and that is precisely why his critique remains uncomfortable even today.

Colonial rule did create new spaces for some Dalits and lower castes, but these were exceptions within a fundamentally intact caste order. The British neither disrupted land relations nor challenged the village power structure; instead, they governed through dominant castes and codified Brahmanical norms as “customary law.” Caste was reorganised administratively, not attacked politically. Contemporary anti-caste discourse often romanticises colonial modernity because it provides a convenient contrast to indigenous oppression and an easy explanation for change. This leads to an overemphasis on legal reform, representation, and symbolic equality, while underplaying material questions—land, labour, housing, and control over institutions. Ambedkar rejected this liberal illusion. For him, caste was not merely a social prejudice but a system of graded inequality, reproduced through endogamy, inherited occupation, and economic dependence. Colonialism left all of this largely untouched.

The deeper problem is that this narrative allows the postcolonial Indian state to inherit colonial structures while claiming moral distance from caste. By framing colonial rule as a civilising rupture, contemporary discourse obscures how modern institutions—bureaucracy, education, markets, and even democracy—continue to reproduce caste hierarchies. Ambedkar’s critique cuts through this self-deception: without structural redistribution and a frontal assault on the social foundations of caste, neither colonial modernity nor postcolonial constitutionalism can deliver annihilation.

How do you assess the long-term political consequences of the Poona Pact? Had Ambedkar’s demand for separate electorates for the Scheduled Castes been realised, how might India’s post-independence electoral and democratic framework have evolved?

The Poona Pact was a decisive political defeat for Ambedkar, and its long-term consequences have been profoundly limiting for Dalit political autonomy. While it expanded reserved seats for the Scheduled Castes, it did so by subsuming Dalit political representation within a Hindu-majoritarian electorate. This structural choice has shaped—and constrained—Indian democracy ever since.

By replacing separate electorates with joint electorates and reserved constituencies, the Pact ensured that Dalit representatives would be elected not primarily by Dalits but by the dominant castes of the constituency. The predictable outcome has been political dependence. SC legislators have been structurally incentivised to moderate their agendas, avoid antagonising dominant caste voters, and function as intermediaries rather than as autonomous representatives of Dalit interests. Over time, this has produced a class of Dalit politicians whose survival depends on party patronage rather than grassroots accountability.

Had Ambedkar’s demand for separate electorates been realised, India’s electoral and democratic framework would likely have evolved very differently. Separate electorates would have institutionalised political self-representation for the most oppressed groups, not as a concession but as a democratic principle. Dalit leaders would have been compelled to develop independent political programmes, organisational capacity, and ideological clarity, answerable primarily to Dalit constituencies. This could have produced a more plural, conflictual, but honest democracy—one that acknowledged deep social cleavages rather than masking them under formal equality.

Critics often argue that separate electorates would have fragmented the nation. But this fear confuses unity with domination. The real fragmentation has been political invisibility and co-optation. A system of separate electorates might have accelerated the emergence of coalition politics grounded in negotiated interests rather than symbolic inclusion. It could also have prevented the monopolisation of national politics by upper-caste elites under the guise of universal representation.

This expectation, however, rests on a stereotypical and uncritical assumption. The choice of electorates within the prevailing framework of the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system might not have produced any different outcome. The FPTP system is resource-intensive and elite-friendly. Even in the separate electorate system nothing prevented the dominant-class parties from getting their loyal Dalit candidates defeat the genuine Dalit cansidates by deploying their superior organisational and material resources.

Significantly, Ambedkar never problematised the FPTP electoral framework. On the contrary, he explicitly defended it in the Constituent Assembly when proportional representation (PR) was proposed as an alternative. This position warrants critical re-examination. A PR system would have ensured representation not only for Dalits but for all citizens in proportion to their political preferences, without attaching representation to caste or community identities or reproducing the stigma associated with “reserved” constituencies. In retrospect, Ambedkar’s defence of FPTP appears as a serious historical misjudgment. By aligning with a system structurally biased towards dominant parties and resource-rich elites, he inadvertently helped entrench a model of representation that limited the scope of genuine political inclusion while normalising elite capture under the guise of formal equality.

Ambedkar’s Independent Labour Party sought to unite workers, peasants, and Dalits on an anti-caste and anti-capitalist platform. Do you think Ambedkar’s critique of capitalism failed to gain lasting traction among his followers and later Dalit political formations?

Yes. Ambedkar’s critique of capitalism did not acquire lasting traction among his followers or within subsequent Dalit political formations. This was not accidental. It was only during his Independent Labour Party (ILP) phase that Ambedkar spoke with clarity against Brahminism and capitalism as conjoint enemies of Dalits. In the later period, particularly with the formation of the Scheduled Castes Federation, the growing emphasis on representation, constitutional safeguards, and electoral politics eclipsed his earlier anti-capitalist rhetoric. This shift was further accentuated by Ambedkar’s explicit anti-communism and his deep distrust of Marxist organisations.

Ambedkar grasped earlier than most Indian Marxists that caste and capitalism in India were not separate or sequential systems but mutually reinforcing ones. He rejected the orthodox Marxist assumption that capitalist development would erode pre-capitalist hierarchies. In a caste society, capitalism does not dissolve hierarchy; it reorganises and modernises it. The ILP’s political programme reflected this insight by attempting to weld workers, peasants, and Dalits into a single political bloc against both caste domination and class exploitation. This project, however, confronted two structural limits. First, the Indian working class itself was deeply fractured by caste, and socialist movements largely refused to confront caste as a constitutive structure rather than a secondary contradiction. Second, Dalit masses emerging from extreme material deprivation understandably prioritised immediate social dignity, legal protection, and political safeguards over a sustained and abstract critique of capitalism.

After Ambedkar’s death, Dalit politics increasingly narrowed its horizon to state-mediated inclusion—reservations, welfare schemes, symbolic recognition, and electoral bargaining. These gains were real and hard-won, but they came at a cost. Capitalism increasingly came to be viewed less as a structure of exploitation and more as a neutral, or even enabling, terrain, provided Dalits could secure access to its opportunities. The result was a politics oriented toward redistribution and inclusion within the existing order rather than the transformation of that order itself.

The deeper failure, however, lies as much with the Left as with Dalit movements. By relegating caste to the status of a “superstructural” issue or a residual identity problem, Marxist parties forfeited the possibility of a durable alliance with Ambedkarite politics. In this vacuum, Dalit political formations gravitated toward identity-based mobilisation and transactional alliances with dominant parties, including those openly committed to neoliberal restructuring. Among sections of the educated Dalit middle class, this drift manifested in an open endorsement of neoliberal capitalism as the vehicle of Dalit emancipation, articulated through oxymoronic formulations such as “Dalit capitalism” and a “Dalit bourgeoisie.”

The problem, therefore, is not that Ambedkar’s critique of capitalism was intellectually weak. It was politically orphaned. In the absence of an anti-caste Left, and without Dalit movements willing or able to sustain a systemic critique of capital, Ambedkar’s radical synthesis was reduced to selective appropriation. What survived was Ambedkar as a symbol of dignity and rights, not Ambedkar as a theorist of political economy and structural domination.

After Independence, the Congress outlawed untouchability through Article 17, yet showed little commitment to the annihilation of caste. Why did the abolition of caste never become a serious agenda within India’s parliamentary democracy across parties and decades?

Because annihilation of caste is structurally incompatible with the way India’s parliamentary democracy has been designed, operated, and stabilised since Independence. Article 17 outlawed untouchability, not caste. That distinction is not incidental—it is foundational.

During colonial rule, untouchability became an embarrassment for Western-educated Hindu reformers. They denounced the practice, but none—including Gandhi—questioned the caste structure that produced it. Untouchability was treated as a moral stain, not as a logical consequence of caste itself. Unsurprisingly, in the Constituent Assembly—overwhelmingly dominated by the Congress—the motion to abolish untouchability passed without resistance. The few who pointed out the obvious contradiction—how can untouchability end if caste remains intact?—were ignored. The system was left standing; only its most visible disgrace was targeted.

For the Congress leadership, the abolition of untouchability functioned largely as a moral gesture—symbolically powerful but politically inexpensive. It disrupted little and threatened no entrenched interests. The annihilation of caste, by contrast, would have required dismantling the very social infrastructure on which electoral mobilisation, rural governance, and elite consensus depended. The Congress inherited a state apparatus that governed through caste rather than against it, and it chose to continue this mode of rule. This decision was constitutionalised, with the tacit justification that castes were necessary instruments of social justice for the oppressed.

Beyond these constitutional manoeuvres, caste hierarchies structured village power, land ownership, local administration, and electoral arithmetic. Political authority in rural India was mediated almost entirely through dominant castes, which formed the backbone of Congress’s post-Independence hegemony. To confront caste at its roots would therefore have meant alienating these agrarian elites and undermining the material bases of Congress rule. The choice was clear, and the Congress made it.

Parliamentary democracy further entrenched this logic. Elections reward aggregation, not transformation. Parties mobilise caste blocs; they do not seek to abolish the principle of caste-based mobilisation itself. Over time, caste became a technology of representation—a way to manage social conflict within the system rather than resolve it. Even parties that claimed to speak for the oppressed found it electorally rational to negotiate caste interests rather than pursue a universal anti-caste programme that would destabilise their support base.

Across decades, this produced a bipartisan consensus: caste would be managed, not dismantled. Social justice was redefined as quotas, welfare schemes, and symbolic inclusion—important correctives, but carefully circumscribed. Structural measures that could actually erode caste—land redistribution, common schooling, housing integration, and radical labour reform—were consistently avoided because they threatened entrenched interests across parties.

The deeper reason is ideological. Indian democracy was built on the fiction that political equality could coexist indefinitely with social hierarchy. Ambedkar warned explicitly that this contradiction would hollow out democracy from within. His warning was ignored because confronting caste seriously would have required a politics willing to rupture consensus, redistribute power, and risk instability.

In short, caste abolition never became a serious parliamentary agenda because caste is not a residue of Indian democracy—it is one of its organising principles. Annihilating it would require a democratic transformation far more radical than any party has been willing to undertake.

(to be continued)