A Village Declares Itself Caste-Free: A Quiet Revolution from Rural Maharashtra

On February 5, 2026, the village of Soundala in Maharashtra unanimously declared itself “caste-free” at a special Gram Sabha, grounding its decision in the values of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity enshrined in the Indian Constitution. In a country where caste continues to shape social life and opportunity, this resolution represents a rare grassroots effort to translate the egalitarian vision of B. R. Ambedkar into lived reality.

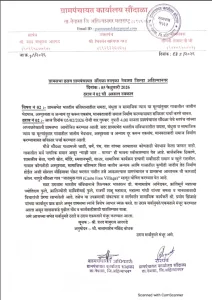

On February 5, 2026, the village of Soundala in Maharashtra’s Ahilyanagar district undertook an act of rare moral and political audacity. At a specially convened Gram Sabha, residents across caste locations-Savarna, Bahujan, and even a few Muslims-voted unanimously to declare their village “caste-free.”

The resolution, drafted in Marathi, opens by invoking the Constitution of India and its Preamble, foregrounding the foundational values of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. “From now onwards, in Soundala village, no one will follow caste or indulge in any form of caste practices. Instead, humanity is the only religion that the villagers will follow,” the resolution affirms. In doing so, it anchors a local moral commitment within the normative architecture of the Republic.

Before placing the resolution before the Sabha, Sarpanch Sharadrao Argade organised a voluntary blood donation camp in which over 200 villagers participated. As proceedings commenced, he addressed the gathering with a simple yet resonant observation: “Our blood is not green or blue. It is simply red. And once it mixes, no one can ever separate it again.”

In a society where caste frequently determines birth, dignity, occupation, and, at times, even death, this gesture was far more than symbolic. It was a political statement, a constitutional reaffirmation, and a historically significant intervention.

This was not Soundala’s first engagement with progressive social reform. In earlier years, the village had passed resolutions addressing gender justice and social equity by prohibiting child marriage, permitting the remarriage of widowed women, taking action against domestic violence and dowry practices, ensuring girls’ access to higher education, and expanding women’s participation in political and social life. The declaration of caste abolition emerges from this sustained culture of ethical introspection and collective reform.

Understanding Caste: India’s Deep Social Wound

For a global readership, caste can be conceptually elusive. Unlike race, which is often visibly demarcated, caste is an inherited and rigid system of social stratification embedded in the subcontinent for centuries. It assigns individuals to graded hierarchies of ritual purity and pollution, circumscribing whom one may marry, dine with, worship alongside, or even physically touch.

At the base of this hierarchy are Dalits, formerly designated “untouchables”, who have endured systemic violence, spatial segregation, and entrenched exclusion. Although “untouchability” was constitutionally abolished in 1950, caste discrimination persists in housing, education, employment, and matrimonial practices. Honour killings and caste-based atrocities remain a grim reality in many regions.

Ahilyanagar district itself has witnessed severe caste violence in recent decades and has long been categorised as an “atrocity-prone” area. That Soundala has emerged from such a context to publicly renounce caste practices renders its decision especially consequential.

Ambedkar’s Unfinished Revolution

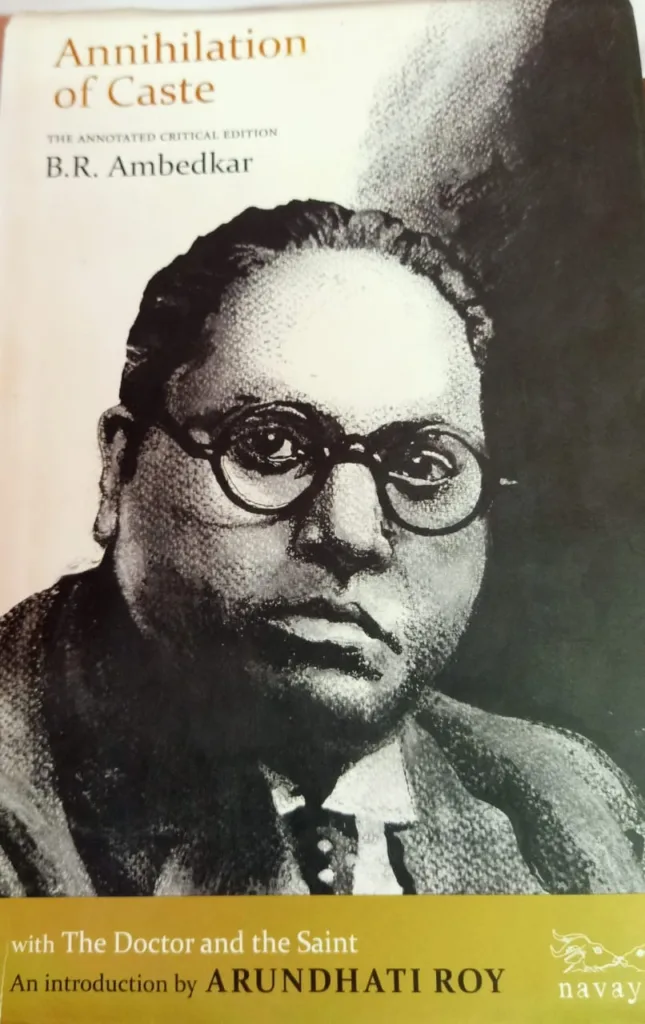

No serious reflection on caste can bypass B. R. Ambedkar the jurist, economist, principal architect of India’s Constitution, and the most uncompromising critic of caste hierarchy.

Ambedkar famously argued that caste is not merely a division of labour but a division of labourers and a system that fractures human solidarity and denies fraternity, the moral substratum of democracy. In his seminal 1936 treatise Annihilation of Caste, he contended that political democracy cannot endure without social democracy. Liberty, equality, and fraternity must be embodied in lived social relations rather than confined to constitutional text.

By explicitly invoking the Constitution and its Preamble, Soundala situates its resolution within Ambedkar’s normative horizon. Caste, in this vision, is not a benign cultural identity to be preserved but a regime of graded inequality to be dismantled. Ambedkar did not assume caste would wither away through economic growth or incremental reform; he insisted that it required conscious social revolt. What Soundala has attempted is precisely such a collective and moral repudiation.

From Constitutional Morality to Village Praxis

The resolution stipulates that no resident shall observe caste practices and that “humanity is the only religion.” It further provides for penalties against conduct that contravenes constitutional values.

This is crucial. Caste persists not merely as abstract ideology but as quotidian practice of separate utensils, segregated seating, restrictions on temple entry, and strictly endogamous marriages. By rendering such practices socially unacceptable within its jurisdiction, Soundala translates constitutional morality into communitarian ethics.

The Gram Sabha, India’s most immediate democratic forum, thus becomes the locus of transformation. This is democracy from below. It is also an affirmation of ‘Swaraj’ in its most substantive sense: not merely administrative decentralisation, but the ethical self-governance of a village republic. Justice here is neither awaited from distant institutions nor deferred to higher authorities; it is enacted through collective deliberation and responsibility.

The caste-free declaration builds upon Soundala’s earlier progressive resolutions, consolidating a trajectory of sustained social reform rather than an isolated moral gesture.

Why This Matters Beyond India

Across the globe, societies confront entrenched systems of racial, ethnic, class, and religious exclusion. While caste is historically specific to South Asia, it resonates with other hierarchical orders that naturalise inequality.

Soundala’s initiative offers several broader lessons. First, legal abolition alone does not dissolve deeply embedded hierarchies; they endure unless consciously dismantled. Second, local democracy can assume a radical character. Transformative change does not invariably originate in parliaments or apex courts; it can germinate in village assemblies and grassroots deliberations. Third, symbolic acts acquire transformative force when sustained by collective conviction.

The blood donation camp preceding the resolution was not theatrical embellishment; it was civic pedagogy. It dramatised a biological truth that subverts hierarchy: human blood, once mingled, defies classification.

Is Caste Really Gone?

To declare a village caste-free is not to erase centuries of prejudice overnight. There are as yet no reported inter-caste or inter-religious marriages in Soundala. Structural inequalities such as land distribution, economic disparities, and educational gaps still remain persistent features of rural India.

Yet to dismiss the initiative as merely symbolic would be to underestimate its disruptive potential. Caste endures because it is normalised, because it is woven into the fabric of everyday life. When a community collectively asserts, “Not here. Not anymore,” it unsettles that normalisation and recalibrates the moral centre of social interaction.

Ambedkar once cautioned that Indians may enter political life as equals but exit into society as unequals. Soundala’s experiment seeks to invert this paradox by embedding social equality at the grassroots.

The Larger Political Context

Contemporary India is marked by renewed polarisation along religious and caste lines. Electoral mobilisation frequently capitalises on identity rather than dismantling structural hierarchies. In such a milieu, a village publicly privileging fraternity over division assumes a quietly subversive character.

By rooting its declaration in the Constitution, Soundala affirms a civic nationalism grounded in shared rights and obligations rather than majoritarian assertion. It reminds the nation that the Preamble’s promise of Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity is not ornamental rhetoric but a binding social covenant.

The Road Ahead: From Declaration to Annihilation

The significance of Soundala lies not solely in the act it has performed but in the horizon it gestures toward. Ambedkar called not for the reform or softening of caste, but for its annihilation as a system of graded inequality. Such annihilation entails sustained social transformation: encouraging inter-caste dining and marriage, ensuring equitable distribution of land and resources, rigorously enforcing anti-discrimination laws, reforming curricula, and cultivating constitutional morality as lived culture. Soundala’s resolution is thus a beginning, a modest yet profound experiment in social democracy.

If even a fraction of India’s approximately 600,000 villages were to initiate similar deliberations, the cumulative effect could prove transformative. The reconstitution of social relations, undertaken from below, may yet alter the moral topography of the nation.

A Red Drop of Hope

When Sharadrao Argade observed that blood, once mingled, cannot be separated, he articulated more than metaphor. He evoked fraternity, the value Ambedkar regarded as the animating spirit of democracy.

In a world fractured by hierarchies and hardened identities, Soundala’s declaration stands as a reminder that the annihilation of caste is neither an abstract academic preoccupation nor a deferred utopia. It is an urgent, practical, and collective undertaking. And at times, revolutions begin not with slogans reverberating through capitals, but with resolutions quietly affirmed in village squares.

Reference: The Wire