When Rivers Become Weapons: Lessons from China’s Blockade of the Brahmaputra – Part 2

China shares major rivers with India and other countries, with water being central to its industrial plans. As China faces a growing water crisis, it may increasingly depend on the Brahmaputra, raising tensions with India and risking conflict. Diplomatic focus must shift to managing shared water resources with restraint and foresight, especially in the face of climate change. Ecological disasters ignore borders and cannot be resolved through war or nationalism; they only lead to widespread destruction and displacement.

Hidden water conflicts in border disputes

Disputes over the Indo-China border began long before the birth of independent India. There have been numerous military confrontations, diplomatic talks and a war over the two sides; however, they have not evolved from what would normally be a border dispute. However, with the dawn of the new millennium, as the Chinese government moves ahead with the construction of dams in the Himalayan waters and mining operations, and with the Indian government building a dam network in Arunachal Pradesh, the Indo-China border disputes are becoming indicators of future water wars.

Yarlung-Brahmaputra-Jamuna

China shares four major rivers with India and other neighboring countries. The most important river is the Yarlang Sangpo, which is called the Brahmaputra in India and the Jamuna in Bangladesh (not the Yamuna River). The Brahmaputra River is one of the widest rivers in the world—50% (2,70,900 sq km) of the Brahmaputra River Basin is shared by China, 36% (1,95,000 sq km) by India and the rest by Myanmar and Bangladesh. The Brahmaputra basin has a population of about 63 million in the four countries mentioned above.

It can be seen that water is a key component of China’s planned industrial growth. The Chinese industrial sector consumes 120 billion cubic meters of water annually. The country’s coal mining sector is also demanding similar water use. Aimed at the country’s growing water and industrial growth, the Chinese government’s planned “Western China Development Strategy” aims at the massive exploitation of Tibetan natural resources—mainly minerals and water. Chinese experts estimate that the generation of electricity from the Yarlang Sangpo River is 114 gigawatts (Managing the Rise of a Hydro-Hegemon: China’s Strategic Interests in the Yarlung-Tsngpo river, Jesper Svensson, IDSA Occassional Paper, No-23). Work on the 550 MW Sangmu project has already begun. In addition to this, China has also planned to add another 20 hydropower projects in the Yarlong basin.

Jasper Svensen reports on March 28, 2011, that the Chinese official newspaper People’s Daily reported that these are projects that could provide 700 million cubic meters of water for the development of the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

During various diplomatic negotiations, the Chinese government has repeatedly assured Indian authorities that they are “convinced of their responsibilities as an Upper Riparian State”. Chinese experts explain that their projects on the Sangpo River are ‘run of the river’ (the run-of-the-river project, which is characterized by the use of turbines to generate electricity without interrupting the flow of rivers). However, Delhi-based Center for Policy Research (CPR) professor and water security expert Brahma Chellani rejects China’s claims by evaluating China’s water use and dam construction practices. “From the Yangtze to the Mekong, and now in Brahmaputra, China’s dam-building pattern is quite accurate. China plans to build 12 dams on the surface of the Brahmaputra. Work on the mid-range one has already begun. These dams not only affect the flow of water but also prevent nutrients from flowing into the lowlands. This would adversely affect agricultural activities in the lower basin” (Simon Denyer, “Chinese Dams in Tibet Raise Hackles in India,”Washington Post, February 7, 2013).

In addition to its domination of the Himalayan watershed, the Chinese government is also pursuing plans to mine a wide variety of precious minerals in the Tibetan region. ‘The South China Morning Post’ newspaper quoted Chinese geologists as saying that the region contains $ 60 billion worth of gold, silver and other precious minerals for the electronics industry. The paper reports that the massive mineral deposits in the Tibetan region have led to an unprecedented increase in population (How Chinese mining in the Himalayas may create a new military flashpoint with India, Stephen Chen, South China Morning Post, 20 May 2018).

Brahmaputra is considered to be one of the most important rivers in India. Eight important hydropower projects have been built in Brahmaputra and tributaries across the states of Arunachal and Assam. State governments have given permission for the construction of hundreds of hydroelectric power projects in the Brahmaputra basin as a response to the Chinese presence in the Himalayas, while addressing the country’s growing water problem. From 2000 to 2016, Arunachal Pradesh government sanctioned 153 water projects. The Indian Exploration Team has not been able to find any profitable mineral deposits in the region, and so far, there have been no such moves for mining on the part of India.

At the same time, the government of India has greatly increased its military presence in the region, as it is suspicious of Chinese development activities in the border areas, especially in Tibetan Autonomous Areas. The construction of airports, missile launching pads, and other military bases is widely undertaken across the border.

It is clear to those who seek to understand the global water disputes that the lower riparian countries are suspicious of the upper riparian countries in the case of different nations sharing common river basins. The Brahmaputra is a case in point. Indian authorities have accused China of developing several water projects in violation of international river water utilization norms. India has complained about projects other than the run-of-the-river projects.

According to the 2006 India-China Expert Level Mechanism on International Rivers, China is obliged to transfer hydrological data to India from May 15 to October 15 every year. China has been refusing to hand over data since the Docklam stand-off that happened in 2017. It was a move that would endanger the lives and property of the people living in the lower riparian areas. The hydrological data available during the monsoon period enable the authorities to prepare for the flood potential of the Brahmaputra. Chinese authorities have, however, unilaterally withdrawn from providing this essential information.

The collapsing Himalayan ecosystem

The military interference in the Himalayan region by two major Asian countries is disrupting the peaceful atmosphere in South Asia. There is no doubt that this intervention will have long-term effects on the ecology of the Himalayan ecosystem, which is already facing a major crisis.

The climate-related issues have made the existence of the Himalayan ecosystem precarious. Even a slight change in the atmospheric temperature will increase the extent of the glacier melting in the Himalayas. This will lead to frequent flooding as well as Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs). This is moving towards creating constant uncertainty in the lives of humans living in the Himalayan Valley. Extreme weather events such as floods, landslides, GLOFs, and droughts are likely to cause more damage in these areas. When we are planning large scale development activities aimed at economic growth, we are likely to overlook the reality that extreme weather events of this nature are causing huge losses to the economy.

China’s large-scale construction and mining operations in the Upper Basin region have long-term effects on the Brahmaputra basin. Tibet is dubbed ‘Asia’s Water Tower’. The Tibetan Plateau is a crucial water source and storage for China, whose unevenly distributed water resources are said to be in crisis. The Himalayan ecosystem is adversely affected by the fact that both countries are increasing their military presence in the region. Based on the statistics of the frequency of natural disasters in the region and the number of people affected in the last century, flood disasters have major significance. At the same time, drought is the main villain when it comes to famine. The reality is that large-scale construction projects in the region are the root cause of this change. It is a fact that any change in the Himalayan ecology, which directly affects the lives of over 1 billion people in eight Asian nations such as India, Pakistan, China, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Myanmar and Nepal, will lead to massive suffering and economic collapse.

The scientific community has warned that the Hindukush Himalayan region, one of the world’s largest glaciers, is facing such a threat. Official bodies, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), have recognized the severity and seriousness of the problem. According to the World Meteorological Organisation, the average temperature increase in the Hindukush Himalayan region will rise to 1.8 degrees Celsius for at least the next five years. Another indication by the Hindukush Himalayan Assessment Report is that even with all the agreements we have made in the past, the average temperature rise in the region will be 2.1 degrees Celsius. All this suggests that by 2050, about one-third of the glaciers in the Himalayan mountains are going to disappear.

Extreme flooding and severe drought threaten the valley region, causing earthquakes and landslides, destroying mountain life and property. Experts say that climate change is making significant changes in the agricultural practices of the Himalayan region. Studies show that over 30 crops have been stopped in Uttarakhand in the last two decades. The people of Kumik village in the Sanskar Valley, which is part of India, are living examples of climate change. Known as the highest village in the world, Kumik is facing a severe water shortage today. The Kumik inhabitants, who have been engaged in agricultural pursuits in the Himalayas for centuries, had to leave their village and migrate to other places. Perhaps the first ecological refugees in India to have fled climate change were the inhabitants of Kumik. Degradation of glaciers has created a crisis for the villagers who depend on the springs that originate from the Himalayas. They had no choice but to leave the village. This is not the story of a single village only. Hundreds of villages in the Himalayan region are facing a similar fate. The only solution is to reduce the human carbon footprint as early as possible.

Are water wars a reality?

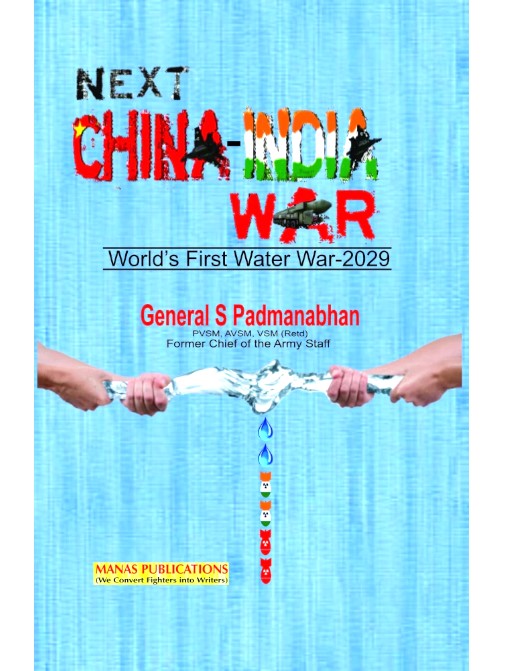

Indian Army Chief S. Padmanabhan wrote a book in 2014, titled ‘Next China-India War: World’s First Water War–2029’. The book predicts that the severe water shortage that China is likely to experience by the end of the decade will drive China to rely more on the waters of Brahmaputra, leading to an inevitable water-war.

The Huffington Post, New York Times, Guardian, South China Morning Post and Washington Post as well as journals such as World Affairs, Project Syndicate, World Review, Geopolitical Monitor have published hundreds of articles and essays on this issue.

In addition, several research papers and books have been published on the same topic. All these pointspoint to the potential for India-China relations to go beyond traditional border disputes into a serious water war. Over the last two decades, however, it can be seen that the key issue in the Indo-China diplomatic negotiations is related to water in the Brahmaputra.

Chinese authorities have always been reluctant to sign legally binding agreements with the lower basin countries. This makes them suspicious of any move by others. There are also rumors that the Chinese government has approved a project to construct a 1000 km long underground tunnel to get Brahmaputra’s water to the heart of China. But there are some other strong arguments that China’s water projects are not dependent on the Brahmaputra and are mainly linked to the Yangtze Yellow River.

Today, there are very clear international standards for how countries located in the upper regions should exercise their natural superiority over the countries in the lower regions of the basin. But China is not the only country in the world that is changing its geopolitical trajectory as a means of upsetting nations located in the lower reaches. A similar interaction can be seen in India-Pakistan relations. The Indian Prime Minister’s statement on September 26, 2016, in response to Pakistani interventions in Kashmir that “blood and water cannot flow together”, was something no Indian Prime Minister had ever done. The fact is that the Indian authorities have not hesitated to raise Pakistan’s anxieties by building dozens of dams across the Indus Valley. International river relations need to be treated with more restraint and foresight, especially when climate change is a reality to reckon with.

Conclusion

Ecological disasters, by their very nature, cannot be mitigated by any amount of flexing of muscles, threatening each other by nuclear weapons or shibboleths of patriotism and accompanying melodrama. They do not recognize national boundaries and cannot be settled through wars. At any rate, they will trigger massive destruction, untold suffering, and an earth-shattering exodus of environmental refugees.

Narrow parochial approaches confined to regional or national boundaries cannot settle interstate water disputes. International bodies such as the UN or international water tribunals can be invoked to arbitrate and settle cross-border water disputes. Principles of equity and justice should be given the topmost priority in settling these issues. The sooner we initiate collective action in this regard, the better. The stand-off between India and China should be settled through peaceful cooperation, not through war. People’s will to pressurize governments into positive action for common good irrespective of their nationalities can culminate in hitherto untried means of resolving this global issue of sharing of water resources.

The End