A World Measured by Walking: Asari Knowledge, Space, and Belonging

In early 20th-century Kerala, the Asari (carpenter) caste resisted both colonial and Brahminical dominance by intentionally rejecting the opportunities provided by colonial institutions. They actively dissuaded community members from engaging with these institutions. Sunandan K.N. explores how this deliberate act of refusal shaped the Asari community’s understanding of progress and how their conception of desham (homeland or locality) differed from mainstream notions. Politics of Ignoring: Stories of Asari Interventions in Colonial Practices in Malabar- Part 2

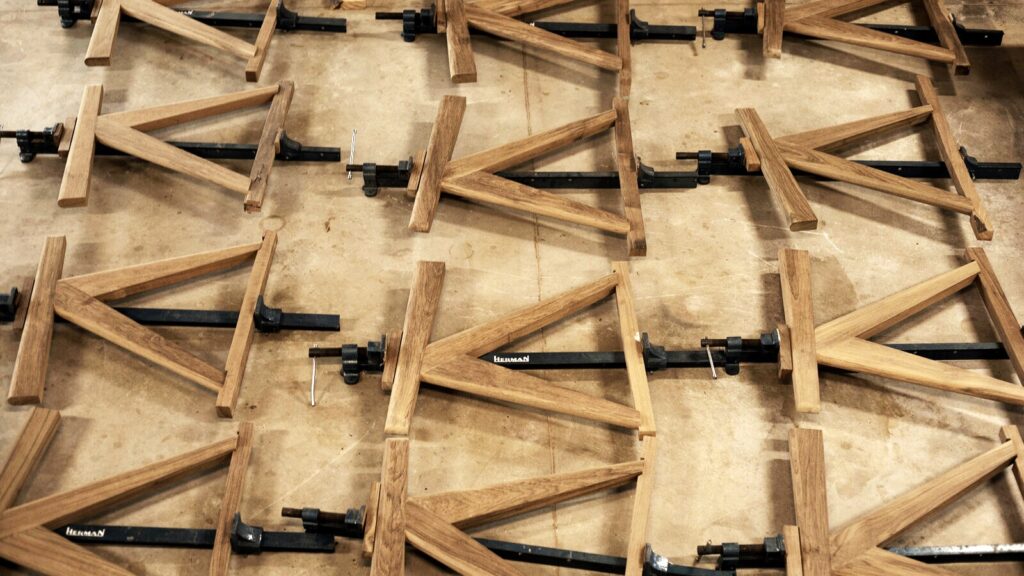

STRATEGIES OF IGNORING: LOCATING ASARIPPANI IN DESHAM

Asaris (carpenters) intervened in this colonial governing practice through a politics of ignoring. On the one hand, unlike many other caste groups in this period, they did not form caste-based reform associations or start the publication of journals or magazines. On the other hand, they actively discouraged members of the caste community from participating in colonial institutions. This ‘campaign’ was organised through daily conversations with family, on occasions like marriage or at the workplace.

Many Asaris remember that their grandfathers were invited to work in towns for the government, and they refused for fear of losing caste. Velayudhan, an 80-year-old chief carpenter from Calicut, remembered his grandfather’s advice that he should never leave the desham, which was conveyed to him in a proverbial form: ‘the moment you leave the desham, the charatu (the measuring string Asaris use) will break’ (Velayudhan 2009). According to Krishnan, a chief carpenter, his grandfather considered ‘sayip (the white man) as evil’ and that ‘they reside in towns’ (Krishnan 2009). Several Asaris I interviewed remember similar stories from their childhood told by their grandparents. The moral of these stories was the necessity of rejecting the temptation of the town, or the importance of locating oneself at a place to which one belongs: the desham.

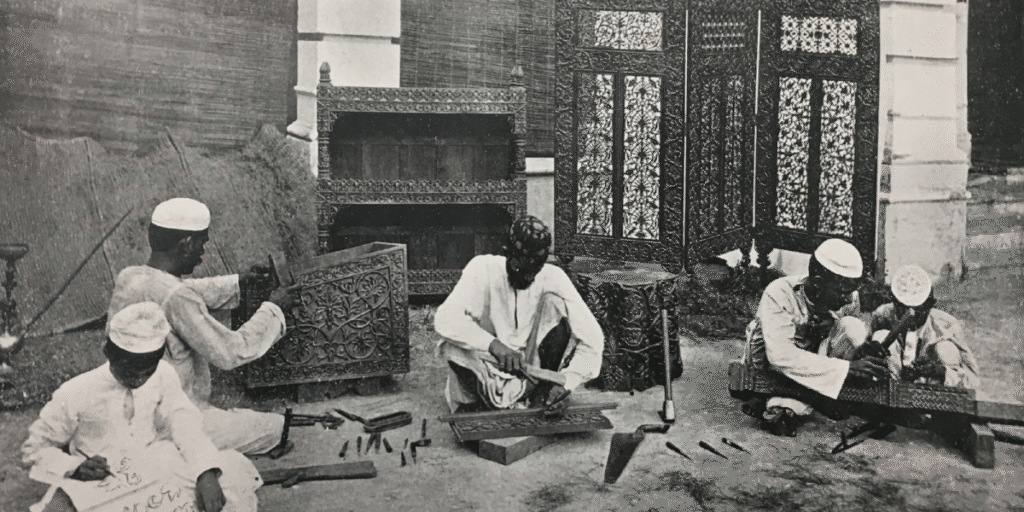

Desham as such did not emerge as a new space in the early 20th century. Even in the pre-colonial period, it was the lowest administrative region and a familiar location for different sections of society. The landlords and agricultural labour castes located themselves in desham for the obvious reason of settled agriculture. However, Asaris, until the Politics of Ignoring: Stories of Asari Interventions in the early 20th century, shifted their location from one desham to another for various reasons. William Logan, while challenging the traditional wisdom that Indian villages were always self-sufficient in material production, noted the mobility of artisanal practitioners. He observed that the mere fact that different sections of the population speak in different accents – and sometimes in totally different languages – underscored the mobility of the population. Logan specifically mentioned that ‘in many occasions, the artisans and the lower-caste people shifted their locations mostly for the reasons of survival’ (Government of Madras 1887: 74).

While describing the procedures of a temple construction he witnessed in Malabar in 1897, W. Arbuthnot observed that ‘the architect, a carpenter, who is originally from a neighboring village, has settled with his family near the temple for the purpose of the construction’. Arbuthnot noted that once the construction was over, ‘he may make this village his permanent location or may move into a different place’ depending on the demand for his expertise (Arbuthnot 1901: 22). Innes and Evans also observed that, though large-scale migration of labour was an unknown phenomenon in the late 19th century, workers, ‘especially carpenters and smiths, were not hesitant to shift into a new village according to the opportunities available to them at different periods’ (Innes and Evans 1905: 36). These observations show that, on the one hand, jobs that were within a desham were not sufficient to survive and hence Asaris had to move from one place to another looking for opportunities. On the other hand, it also shows that Asaris, at this period, did not consider moving out of desham a violation of customs or caste rules.

By the turn of the century, we start observing Asari articulations in which desham becomes the only genuine space of asarippani. In a reply to the collector of Malabar mentioned earlier, the amsham adhikari (village officer) of Purathur, wrote about the difficulty of recruiting Asaris for PWD works. He explained: One of the major objections they (Asaris) raised was based on their affinity to their desham. In one case, I pointed out to a chief carpenter that it was only thirty or forty years ago that his grandfather and his maternal uncle had moved from the neighboring village to the present one. His reply, which was not convincing for me, was that they took a long time to settle in the new locality.

Now it is difficult for him to start again in another place because to work efficiently he has to know the peculiarities of that desham (Government of Madras 1909: 56). The village officer in the above case, who mainly wanted to justify his failure before higher authorities, depicted the Asari arguments as historically incorrect. In a report in 1915, S. W. Johns observed that, though ‘the spirit of progress we brought into this country has reached even in the remotest villages… the parochial nature of the caste artisans has been increasing year by year’ (Government of Madras 1917: 119). The colonisers noted that the Asari claims regarding their affinity to desham was a new phenomenon, but they considered this a mark of the backwardness and inherent parochial nature of the community.

Asaris cared less about the historical correctness of their argument than about a strategy that would help them preserve their authority and independence over their practice. My attempt is not to make any definite claim on the changes in mobility of Asaris before or during colonial intervention. In other words, it is less important to verify whether Asaris were moving from one desham to another before colonial intervention than to note the emergence of a discourse, after colonial intervention, in which Asaris claim that they were located in a desham.

Asaris based their reluctance to move into towns by emphasising the importance of desham as the location of asarippani. Desham in this concept was not only a geographical space but also an imagined social space. Asaris in this period thought of asarippani as a located practice, bounded by the space of desham, crossing which would disable their knowing/practicing capacities. By locating Asarippani in Desham, Asaris connected knowing and space, which was incommensurable with the colonial idea of universal knowledge.

Two written Asari sources from the first half of the 20th century shed some light on the relation between desham and asarippani. Asari Vrithantham (The News of Asaris) is an unpublished palm leaf manuscript written by Neelakantan Achari. Neelakantan Achari learned reading and writing in Sanskrit and Malayalam from an upper-caste teacher named Govinda Variyar. He finished the writing of this particular work in 1932. It is important to note that, even though paper and printing were popular by this time, Achari wrote on palm leaves in a traditional style. In the pre-colonial period, scholars and experts wrote the Sanskrit texts, horoscopes, and almanacs on palm leaves. When paper and printing became the dominant mode of writing, people started associating palm leaf manuscripts with sacred, traditional, or ritual knowledge.

Invoking a traditional method and form of writing, Asari might have been attempting to make his work authentic and look like a traditional text. At the same time, the work itself did not follow any traditional narrative practices. It is in the form of a dialogue between a father and son described both in prose and slokas (verses). The content itself was not mythical or ritualistic but about the contemporary social situation.

Koman, the son in the story, is planning to migrate to Kozhikode (Calicut) town, where he can find a job in the railway workshop. Kandan, the father, in attempting to discourage his son’s wish to relocate, highlights the importance of secluding themselves in desham: An Asari out of his desham Is like a fish out of water. He knows only about his desham , and only that desham knows him. Outside Damascus, he doesn’t know East or West . He doesn’t know the wind or water. Doesn’t know the tree or measure (Achari 1936). Kandan connected Asari and Desham through knowledge. According to him,

the Asari knowledge practice was limited within the geographical space of desham. Unlike colonial knowledge, which once produced can be exported to any place, knowing requires continuous experience, and hence the knower should be located in a space for long periods. By creating a relation between space, experience and knowing, Achari indirectly made a distinction between asarippani and the colonial modes of production of knowledge.

The second source is a travelogue written by Govindan Asari in the second or third decades of the 20th century, which expresses a similar kind of connection between Asaris and desham. Asari left his home near Thalassery in North Malabar in the early years of the 1910s and travelled through the southern part of the Malabar district and also through the neighboring princely state of Kochi. He returned home after three years and started writing this travelogue, most probably in the last years of the 1910s and finished it in 1921. The travelogue begins with the description of his re-entry into his desham. The moment he crossed the bridge at the boundary of his desham, he transformed into his earlier identity as Asari. ‘During the trip I was merely Govindan and at this moment I became Govindan Asari again.’ Even though he enjoyed his travel, he was ‘naturally happy’ only in his desham

because ‘it is only here, I can do my own work which is the responsibility rested on me by the directions of my forefathers’ (Asari 1921).

He also explained how in different deshams Asaris exercised very different procedures and methods. According to him this was another reason for an Asari to remain in one’s own desham. For Govindan Asari, his own desham was always the reference point for comparing the peculiarities of other deshams. Desham in his description was not a space which was always already existing there for him. It was his travel that made him aware of the connection between Asari and desham and this awareness was considered important by him in the new circumstance of sayip’s (whiteman) intervention. He wrote this travelogue mainly to explain this new situation where Asaris had to understand the importance of desham.

Asaris imagined desham through the axes of asarippani. Desham was the boundary of their experience and hence the limit of their practices. The relation between desham and asarippani was not exhaustive in the sense that asarippani could not be explained completely by the parameters of desham or vice versa. Still, this relation played an important role in the Asari articulation of difference in the first half of the 20th century. The Asari imagination of desham was different, say, for example, from that of Brahmins in the same period. For Brahmins, desham was an administrative region or mark of certain controls and powers.

As we observed above, Asaris started invoking desham in the early decades of the 20th century mostly by connecting it with asarippani. We may then assume that it was at this time that Asaris situated themselves in desham, and it was then that desham became a space of belonging and a space of difference-making. Desham, as articulated by Asaris, was not the same as gramam (village), which was one of the central themes of the nationalist discourse, especially in Gandhi’s imagination of the Nation. In the nationalist narrative, village and artisans were inseparably connected. By the beginning of the 20th century, artisans became an important figure in the national movement dominated by the Hindu upper castes. The Indian National Congress, which was the major organisation in the nationalist movement, championed the revival of handicrafts of India, which was being made extinct by the colonial policy of importing industrial products from England. Gandhi’s campaign for self- reliance imagined artisans as the central figure of material production.

Analysing the centre-staging of craft in the nationalist movement, Abigail McGowan pointed out that in the early 20th century ‘crafts stood in for India as a whole economy, society, culture and politics’. She explained that this was ‘the result of struggles between Indian elites and British officials to establish authority over the lower classes as well as the state itself’ (McGowan 2009: 3). Both the colonialists and nationalists imagined gramam as the natural location of artisanal production in opposition to the city, which was the site of industrial production. Gandhi’s idealisation of India as a federation of self-reliant villages incorporated the British Orientalists’ romanticised views of the structure and functions of Indian villages.

Asaris, who refused to relocate to cities, did not accept the romantic space of gramam as their location; it was desham that they considered the place of belonging. The descriptions of Kuttippurathu Kesavan Nair about his village in the second decade of the 20th century indirectly explained how the nationalist imagination of gramam and Asari imagination of desham were different. Nair, an upper-caste poet, was famous for his verses which romanticised the natural beauty of gramam in opposition to treacherous and pretentious cities. In an article in 1921, Nair explained that ‘if there is anything valuable about a city, it is the fact that its emergence helped everyone to recognize the beauty of the village’ (Nair 1921: 35). This beauty was also part of the recognition that his village ‘is not an isolated and remote place, but part of a nation, the culture of which is formed in thousands of similar villages’ (Ibid). It was only when this connection (the connection through the idea of nation) was established that the beauty itself would be revealed. He contrasted this with the imaginations of ‘innocent and poor villagers who have never traveled outside their village. They are unfortunately unable to see their village as beautiful’ (p. 36). This is widely different from the perspectives of Asaris; they understood the village as their place of work.

Appunni, an elderly carpenter in Nair’s village, told him that ‘one should work only where one can learn through walking and one should learn only where one can learn by walking’ (p. 37). According to Nair, the river at the boundary of his desham was the limit of Appuni’s walking. For him that world was ‘a place for working and remaking, not an object for the eyes for which it gives immeasurable pleasure’ (p. 38). Nair’s descriptions showed that for Asaris desham was the world of work, whereas for the upper-caste nationalist, gramam was a world of beauty and innocence.

(to be continued)