The Silence of a Billion: How India’s Parties Crushed the Democratic Will

Why does the world’s largest democracy remain silent even as its freedoms shrink? Asokakumar V’s sharp, uncompromising analysis shows how India’s political parties, shaped by colonial bureaucracy and feudal hierarchy, have captured the public sphere and muted genuine democratic expression.

Across America, thousands of people have taken to the streets in recent years to oppose the anti-democratic turn of the Trump administration. Everywhere one common slogan was heard: “No kings.” More than seven million protesters participated in demonstrations holding placards declaring: “No Monarchy but Democracy,” “We Love America, Not Trump,” and “The Constitution Is Not Optional.”

On 14 June 2025—coinciding with the U.S. Army’s 250th Anniversary Parade and Trump’s 79th birthday—mass protests erupted across the country in what participants called “No Kings Day.” Again, on 18 October, in more than 2,100 locations across cities and towns, hundreds of thousands mobilised in peaceful demonstrations coordinated by over two hundred organisations.

Earlier that year, the President’s powers had been expanded to deploy the army in American cities in the name of national security, overriding objections raised by individual states. These authoritarian measures—together with the criminalisation of immigrants, the withdrawal of basic welfare protections, and the expansion of benefits for the ultra-rich—provoked widespread public anger. In response, ordinary citizens marched peacefully across the nation demanding peace, social welfare, decent wages, employment, healthcare, and humane immigration policies. Leaders of the Democratic Party joined many of these rallies, standing alongside the people. Labour unions, issue-based networks, student organisations, churches, immigrant associations, and digital mobilisation ecosystems also organised in concert, often transcending the boundaries of partisan politics.

This wave of protest is not confined to America. From Berlin and London to Rome and Madrid, people across Europe have declared their solidarity with the American public.

Yet a crucial question arises: why has a comparable mass uprising not emerged in India, despite the fact that democratic erosion here is deeper and more severe—culturally, economically, and politically?

The answer is undeniably multidimensional. It lies partly in the radically different historical trajectories through which democratic institutions emerged in the West and in postcolonial societies like India, and partly in the contrast between the politically awakened middle classes of Western countries and the vast Indian multitudes struggling under the burdens of poverty and daily survival.

At the same time, we cannot simply assume that Indians lack a democratic impulse or a spirit of rebellion. One could counter such a claim by pointing to the overwhelming influence of billionaire money power in the United States and other Western democracies—hardly ideal models of popular sovereignty. Moreover, India has witnessed sustained and courageous mass mobilisations in defence of democratic rights: the farmers’ agitation, numerous environmental struggles, the nationwide protests against the CAA, and civil society involvement in shaping the Right to Information Act and the rural employment guarantee scheme all testify to the people’s readiness to rise when democratic principles are visibly threatened.

Even after acknowledging these factors, a fundamental question remains: do Indians today have the space to express their democratic impulses? Indians arguably have more to say about democracy than Western citizens, for they carry the historical memory of both internal hierarchies and external colonial domination. In the West, democratic rights were shaped largely through conflicts between monarchies and domestic elites. In colonies, people confronted a double burden—caste and class hierarchies internally, and imperial rule from above. Their democratic imagination therefore acquired a depth, urgency, and moral intensity distinct from Western political traditions.

Because democratic impulses in India have long been suppressed—first by empire, now by concentrated political power—the urgency to articulate and protect them is greater than ever.

Among the many factors preventing citizens from expressing these impulses, one stands out: the extreme centralisation of power within India’s political parties. This centralisation now functions as a structural barrier that prevents citizens from realising their democratic aspirations. Indian political parties absorbed a culture of hierarchy rooted both in traditional feudal structures and in the authoritarian, racially ordered bureaucracy of colonial rule.

Postcolonial political parties thus inherited a double legacy—imperial command-and-control systems on the one hand, and the organisational discipline of nationalist mass mobilisation on the other. Western parties also possess centralising tendencies, but these are moderated by long-established institutions of local self-government, internal party democracy, and a pluralist political culture. As a result, citizens in Western democracies often enjoy far greater autonomy from party domination than their counterparts in postcolonial states, even if the strengths of their democracies vary widely.

At the moment of independence, India devoted immense intellectual energy to drafting a democratic constitution, but very little to democratising the internal structure of political parties. The outcome was a paradox: a constitutional democracy without democratic parties. By remaining silent on the internal organisation of political parties, the Constitution offered no mechanisms to promote intra-party democracy or ensure public accountability. Party structures and operations were left almost entirely unregulated.

The Law Commission of India writes:

“Currently, there is no express provision for internal democratic regulation of political parties in India… Section 29A of the RP Act merely requires parties to affirm allegiance to the Constitution, socialism, secularism, and democracy.”

Most political parties emerged as highly centralised organisations, replicating the command structure of the colonial state inside electoral politics. As one study observes, the “chronic lack of internal democracy, coupled with the rise of political corruption and clientelist practices, is a matter of serious concern.”

The Electoral Bonds scheme made this reality impossible to ignore. It allowed parties, especially the ruling party, to receive vast sums of anonymous corporate money beyond public scrutiny. This exposed how centralised, opaque party structures can collaborate with the state to shield themselves from democratic oversight.

Thus, the long-term survival of constitutional democracy in India depends fundamentally on whether political parties themselves can become democratic, accountable, and transparent. A comparison with Western democracies highlights the relative absence of mass, cross-party public protests in India—whether in defence of democratic principles or in solidarity with global causes such as the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

In the United States, political parties function with greater decentralisation and autonomy at local levels. Party workers and representatives are not rigidly aligned under a commanding high command. Even while affiliated with a party, elected representatives typically retain independent opinions and identities.

Candidate selection is a striking example. In American democracy, candidates of the Republican, Democratic, and other parties are not appointed by party leadership. Instead, they are chosen primarily through state-run primary elections or caucuses in which voters participate directly. Although rules differ from state to state, some primaries are open to all voters, others restricted to party members, the underlying principle is clear: candidate selection belongs to voters, not to the party hierarchy.

This model stands in stark contrast to the reality of candidate selection in India. As one comparative study notes: “In developing states, the majority of political parties operate as family enterprises… dynastic and self-centric politics have plagued democratic norms and values.”

As elections approach, candidates are simply announced from above by party leadership. Party members and voters are expected to obey without question. Candidate selection is determined by factors such as money, caste, religion, influence, and loyalty to leadership—not by democratic participation.

Zoya Hasan observes: “Nearly all parties are centralised in their decision-making and have been run from the top down in terms of distribution of party tickets, selection of Chief Ministers and State party leaders, and party finance.”

Of the 5,203 sitting MPs, MLAs, and MLCs examined, 1,106—or 21 percent—come from dynastic political families. Dynastic presence is highest in the Lok Sabha, at 31 percent, and lowest in State Assemblies, at 20 percent. These numbers show that a considerable proportion of today’s elected officials come from long-standing political families. Dynastic politics are not limited to the Congress; even in the BJP, a significant proportion of MPs come from political families.

Having usurped the voters’ right to select candidates, Indian political parties now operate as power centres dominating civil society. Voters have become dependent on party high commands. Their individuality is negated; they acquire political existence only through party affiliation. Just as earlier patriarchal norms held that a woman’s life gained meaning only through marriage, party hierarchies today make independent citizenship nearly impossible—even for intellectuals.

The dominance of party leadership is visible even at the lowest levels. Access to welfare and public services is mediated through party networks. Securing a house through the Life Mission scheme, getting onto a welfare list, or resolving a matter at a police station frequently requires party connections. Political unions act as extensions of ruling parties, controlling appointments and transfers. Without party backing, little moves.

This entrenched hierarchy denies civil society the possibility of expressing independent preferences. Political parties cultivate a culture of mental servitude that trains citizens in obedience.

Political leaders in India enjoy excessive privilege, reverence, and social distance from the public. Unlike in many countries where leaders are seen mingling in public places, such scenes are rare in India.

More troubling is the normalisation of political violence. In several states—Kerala, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh—party cadres act like informal militias. They threaten, intimidate, and even kill rivals. “Political violence in West Bengal is now endemic, with the National Crime Records Bureau documenting an average of 20 political killings annually from 1999 to 2016.”

The victims are rarely elites; they are mostly lower-caste and economically vulnerable party followers—sacrificed like feudal retainers while leaders remain insulated.

Thus, political parties in India have cultivated a culture of violence, obedience, and servitude. The relationship between leadership and ordinary members now resembles feudal hierarchy: leaders hold unquestioned authority; followers act like tenants bound by dependence. Party authorities consciously cultivate mental and physical subjugation among their rank-and-file.

If grassroots members are held captive by economic dependence, clientelism, and fear, then the responsibility for defending democratic values shifts to the middle classes—who possess relatively greater economic autonomy. In America, the middle class has played a crucial role in protests. In India, however, the middle class has mortgaged its autonomy to party networks. To protect its social and economic position, it suppresses its own opinions and aligns with ruling parties.

Worse still, large sections of the Indian middle class have embraced religious orthodoxy and authoritarian sentiment. This was evident in the spectacle of utensil-beating during the pandemic. Today, the same energies are invested in enforcing caste hierarchies and humiliating marginalised groups within universities.

India now exhibits a grotesque form of democracy in which even top positions in universities, academies, and courts—institutions meant to be independent—are filled not by merit but by party loyalists. At the lowest level, positions in neighbourhood committees or Kudumbashree units go only to those who obey party directives.

Under the twin domination of party hierarchies and caste-religious power, the Indian masses live in a form of cultural and political servitude that carries distinct feudal echoes. This explains why mass protests in India rarely acquire the independent, spontaneous character seen in Europe or America. Even when global protests emerged in solidarity with Palestine, India—and even Kerala—remained largely silent.

Political parties in India do not allow the growth of millions of independent citizens. Instead, they cultivate obedient followers. Civil society is not seen as a collection of free individuals but as competing tribes—Nair, Ezhava, Patel, Yadav, and so on. This tribalisation makes wholesale vote-trading possible through deals between party chiefs and caste leaders.

Mass anger, when it does erupt, often reflects party mobilisation rather than independent civil society action. The 1977 post-Emergency movement and the 2011 anti-corruption agitation gained momentum only with the support of non-Congress parties. The farmers’ protest, though massive, remained geographically concentrated. Movements like the ASHA workers’ protests show how party allegiance obstructs solidarity even around shared struggles.

This essay does not claim that American or Western democracy is flawless or monolithic, nor that their party systems are perfectly democratic or free of corruption. Money shapes electoral politics profoundly. Yet compared to India, Western civil society enjoys far greater space to act independently of party control. This space enables citizens to organise beyond party lines and bring millions into the streets.

The future of Indian democracy depends above all on the rise of a civil society capable of challenging the structures of party domination that deny intra-party democracy. The first freedom civil society must win is freedom from party power itself. Yet this is precisely where the challenge lies. India’s electoral system is entrenched in party supremacy, characterised by a lack of internal democracy and virtually no mechanisms of public oversight.

Breaking this vicious circle and enabling millions to build an autonomous civil sphere, independent of party control, is therefore one of the most difficult tasks before Indian democracy.

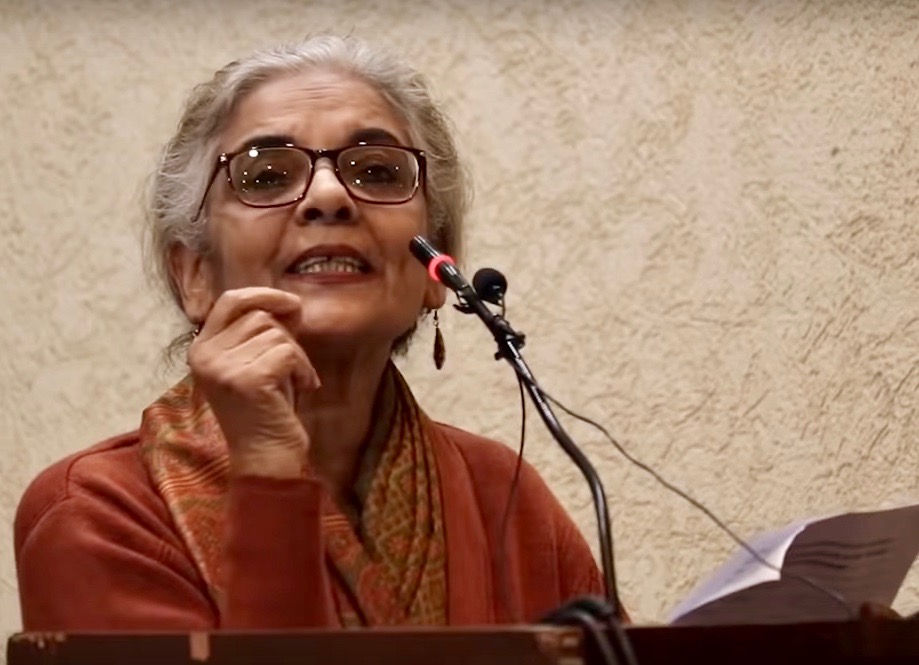

Featured Image: The Occupy protesters made the catchphrase “We are the 99%” part of the national conversation.Image courtesy: CNN

The article was originally published in Malayalam on Truecopy Think.