The Forgotten Stream: Resisting Cultural Nationalism in Indian History

One of the most notable critical studies on nationalism in Malayalam scholarship is E. Ratheesh’s 2022 thesis, “Indian Cultural Nationalism and Malayalam Criticism: An Inquiry Based on Selected Texts”. The thesis was submitted under the guidance of Praseetha P. at the Department of Malayalam and Kerala Studies, University of Calicut.

Dr. Radhakrishnan Ilayidath, a faculty member at Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University, critically analyzes the unique features and content of this work. The thesis argues that a counter-current resisting the interests of cultural nationalism and Hindutva has always existed in India. Preserving and continuing this counter-current, it insists, is a pressing contemporary academic responsibility.

The pluralistic nature of India must be recognized as central. Its strength lies not in exclusion, but in inclusion and this, the thesis contends, must be firmly upheld.

Part 1

The thesis shapes its premises on the basis of contemporary dangers in extreme Hindutva. Cultural nationalism is something that transforms into national hindutva as well as cultural hindutva based on need. This thesis argues that there existed a stream always in India that resisted the interests of cultural nationalism and political hinduism. It is a contemporary academic responsibility to sustain this stream. India’s diversity is crucial in this context. It has to be emphasized that the core is not in exclusivity, but in inclusiveness.

The thesis attempts to form a counter history in the perspective of historical knowledge. In the making of counter history, the ancient – medieval history of India and the debates and struggles over nationalism become clearer. The subaltern mass struggles are represented empirically. The thesis makes use of minor struggles and obscure memories in order to create history. Thus this thesis serves to solve an existing problem in the making of Dalit history.

Nation and nationalism: clarity in conceptualisation

The thesis is at the same time explanatory and critical. The clarity of conceptualisation of this dissertation is exemplary. See how nation and nationalism are interpreted by the dissertation. Nation is a factual reality. It stands by itself on the basis of race, landscape, language, history, and boundaries, and stands in contrast with other nations on the basis of certain other factors. Nationalism is formed when, in order to protect the above-mentioned factors of the nations formed as a result, they get into conflicts or competition with other countries. Which means, nationalism can serve as a doctrine on which a nation can be constituted.

Nationalism, an idea that took shape by the 18th century remains connected with other ideas of modernism. While it is liberating in the context of colonisation, elements of racism remain inherent in it. While the legacy of arsham and sanatanam was interpreted as the content of nationalism, there was also an upheaval against it in India. Hence nationalism can be regarded as the philosophical form of similarities and differences. This way, nationalism can be regarded as a grand narrative that contains diverse streams of thought, and the dominant ones in them, and their critical counter currents.

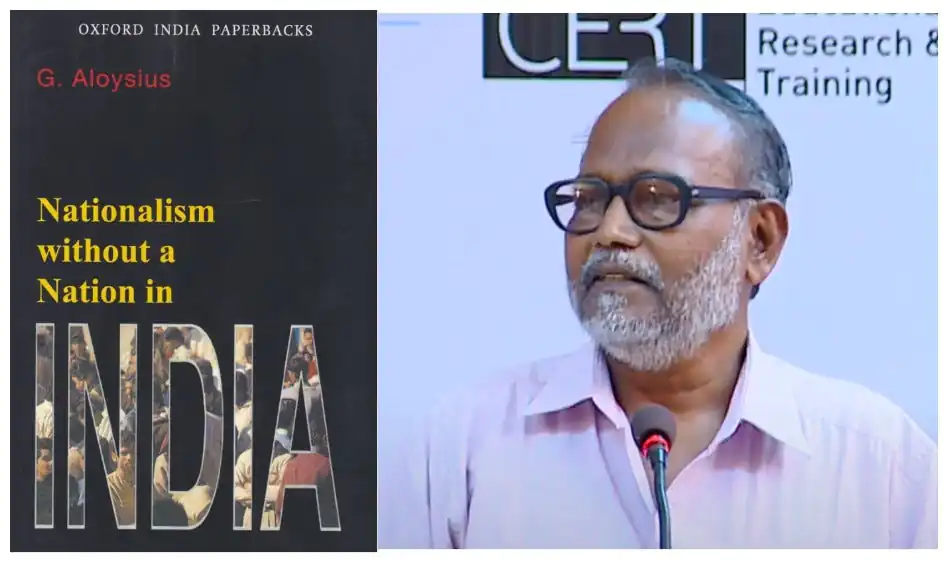

The thesis examines different viewpoints on nationalism. It foregrounds the observations of Prof. G. Aloysius(an Independent research scholar and a social activist) as well as the hypothesis of political nationalism. The metaphorical analyses of nationalism had made it a Western discovery. When one takes into account the mutuality of culture and authority, its content becomes significant. Aloysius says that nationalism was manifested in India in a very low-key manner and that foreign nations influenced it, and that colonization was unable to solve the contradictions in pre-colonial India. Neither the leaders of the nationalist movement nor the British were able to identify the multifaceted advancements in India. The British idea of development ignored the diversity of Indian society, and reduced their problems as mere social problems. Political nationalism is an idea that upholds such uprisings.

In order to unravel the history of nationalism based on fraternity, the thesis uses Zizeks assumptions on ideology. Zizek sees ideology as the common man’s reaction towards power structures. In Zizek, one can see attempts to address people directly while remaining in touch with human imagination.They are not centred around constitutional values. He corrects the common belief that ideology is a false notion, and that it is the belief of the oppressed. He believes that ideology is what has been created by opposing perceptions.

Cultural Nationalism and Hindutva

The thesis analyses two opposing schools of thought centered on culture within the discourse of nationalism. The Cultural nationalistic stream contains British political powers, representatives of the privileged, European orientalists, German indologists, and early historians. One can perceive in them the path of standardisation that manifests diversity through a single lens. They place culture as static even in the context of reformation. Basing the brahminical interpretation, this stream excludes the outcast and the downtrodden. This is something that forms as a result of discarding the multi-facetedness of civilization. This stream doesn’t take into account caste oppression.

The cultural nationalistic debate took shape as a result of the assimilation of centuries-old hegemony. The oppressed sections who wielded power in the modern and postmodern contexts expressed their traditions as being superior in the nationalistic context as well. Thus, a culture was constructed that was unique and lofty. This common model was made by creating idealized archetypes and excluding numerous others. This marked the beginning of cultural nationalism that turned the Indian people casteist. The documents that the Orientalists and British authorities received were about Brahminical supremacy. It is through their intervention that the discerning environment for Indians to understand the framework of India was created. The nationalistic cultural model thus becomes one of the resurrections of the Hindu renaissance. It is important to understand the connection of such models with the formation of racial theories in the global scenario.

Cultural nationalism gained strength towards the end of the 18th century in the backdrop of the Bengal Renaissance. The nationalist movements, leaders, literature, art, and history contributed to this. When liberal national leaders accepted cultural nationalism without criticism, religious fundamentalists blew it up to aggressive proportions.The collection of ideas of cultural nationalism includes religious and caste animosity, oppression of women and Dalits, rejection of Science, and brahminical supremacy .

Hindutva acquires new interpretations in its engagement with modernity. In the 1920s, under the influence of Gandhi, parallel to Indian National Congress becoming popular, the Hindu National Movement also grew. The Hindutva nationalists saw racial nationalism as their doctrine. One can perceive in Raja Ram Mohan Roy the tendency to discard social evils and align Sanatan Dharma with the essence of Hinduism. Seeing that the divine ( Brahma) is situated in man’s soul, Roy’s Brahmo Samaj discarded the intermediary between God and man.

When we talk about the history of Hindutva discourse, the dissertation mentions organizations such as the Arya Samaj, Hindu Sabha, Hindu Samghatan, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Jan Sangh, etc, and the four key figures such as Dayanand Saraswati, Vivekananda, Aurobindo, and Savarkar. Kesav Chandra Sen and Dayanand Saraswati, who led the Brahmo Samaj after Raja Ram Mohan Roy, gave importance to the supremacy of the Vedas. Dayanand Saraswati’s ideal nation was Aryavartha. While clamouring for Sudras’ right to education, Dayanand Saraswati didn’t discard the caste system. He criticised Kabir and Guru Nanak. Aurobindo believed that the way out of slavery is by imparting manliness among Indians. His view was that national awakening wouldn’t be possible without religious upheaval. Vivekananda said that the rejection of caste/religion was the reason for India’s decline. Caste gives a person the freedom to manifest their inherent nature. Seeing Brahmanism as the ideal of humanity, Vivekananda saw rejection of Sanskrit as a terrible sin. On this basis, Ramanujan, Kabir, and the Buddha appeared to him as hypocrites.

It is through concepts like Arya, Aryavarta, Arsha, Sanatan, Bharatavarsha, Akhand Bharat (undivided India), etc., and geographical imaginations that the making of the Hindutva nation in cultural nationalism becomes possible. It was an attempt to make these monologic ideas universal components. It was also an opposing standpoint to the ideas of colonial historians that the West doesn’t have a history. Thus, Hindu nationalism attained a concrete political form in the 19th century.

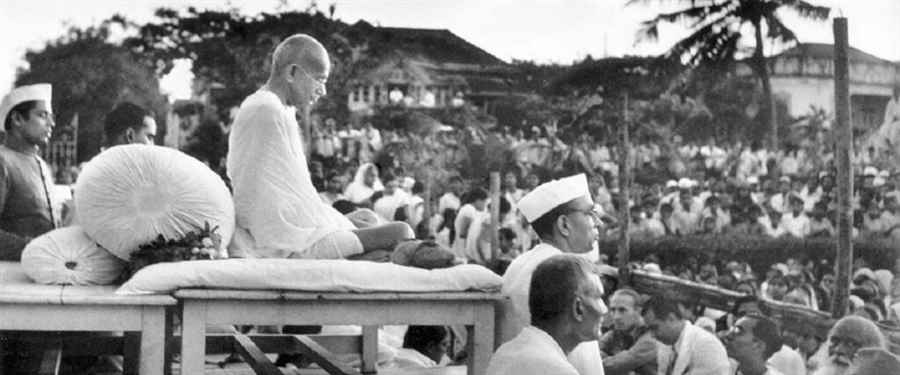

After the death of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, in the 1920’s, the influence of Gandhi in the Indian National Congress became stronger. Anti colonialism ideas based on slogans such as truth, non violence etc were executed by Gandhi. The Hindu Mahasabha, which had been tactically accommodated within the Indian National Congress, transformed by the 1930s into a fiercely religious and independent organization. The literary public sphere, which failed to recognize the violence inherent in Brahmanism, became a shield for cultural nationalism. Discourses on the hegemony of culture never even became part of Indian National Congress. Gandhi developed the notion of Hindu culture as a religious culture, while Savarkar gave it a territorial interpretation. Both were influenced by global nationalist movements of the time.

By infusing aggressive religious fervor into politics, Savarkar gave ideological strength to Hindutva nationalism. His vision was of a Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation) that positioned Muslims as the primary “outsiders.” He saw the protection of cows, brahmins, and Veda sastras as important. Savarkar started leading the Hindu Mahasabha by the end of the 1930s. His book “Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?” became a foundational text that solidified the idea of a Hindu nation. Savarkar’s ideological successor, M.S. Golwalkar, believed that the weakness of Indian nationalism was the cause of the country’s decline. His worldview identified Muslims, Christians, and Communists as internal threats. The Sangh Parivar organizations are driven by the goal of building a Hindutva nation rooted in Aryan-Brahmin racial supremacy.

The thesis talks about connecting the print culture that strengthened Hindu nationalism with the activities of the Geetha Press and Kalyan monthly magazine. The Geetha Press has a history that combines business, caste, and the politics of polarization. The Geetha Press started with the first translation of the Bhagavat Gita in 1923. Later, it spread widely by addressing the politics of polarization. Cow protection was the proclaimed aim of the Geetha Press. The Geetha Press functioned in the expectation that India would become a Hindu nation. Its articles gave weightage to Hindu Muslim divide, and anti-women stands. At the beginning of the 19th century, many untouchable communities all over India were participating in many activities to raise their social status. Researchers also add that the activities of the Geetha Press and the Kalyan monthly magazine were part of the Vaishya community entering the social structure of the Brahmin community. These stood in stark contrast to the politics of the subaltern communities.

It was as part of communal divisions that Hindi began gaining prominence over Urdu, Hindustani, and Persian in the early 20th century. Over time, this developed into a broad political project. It was precisely during the phase when Hindi was being established as the language of national identity that Hindutva’s claims to cultural dominance were also being constructed.

Gandhi had proposed Hindustani, a blend of Hindi and Urdu, as the national language. Even though the public sphere has increasingly recognized the dangers of Hindutva politics, the ideas of Hindutva continue to persist unconsciously in cultural spaces and in everyday life. In the contemporary context, nationalism is becoming a dangerously tangible political force.

Dharmasastra and Dhammasasana

The dissertation establishes that Buddhist philosophy is different from the ideological frameworks of Chaturvarnya and Brahminism. While Brahminism was about violence and annihilation, Buddhism was about brotherhood and peace. The dissertation highlights the achievements of Ashoka and other rulers in India who embraced Buddhist principles. It points out the essential differences between Dharmasastra (Hindu legal/religious texts) and Dhammasasana (Buddhist teachings). As noted, “Buddhist Dhamma is not the Dharma of the Hindutva order based on Varnaashrama Dharma. Rather, it is an ethical framework grounded in social equality, co-existence, non-violence, public welfare, and compassion toward all living beings” (2022:106).

While Dharmaśāstras interpret Rajadharma (duty of the ruler) through the lens of Varnaashrama Dharma, legitimizing social divisions, Buddhist texts make no such references to caste or hierarchical divisions.

The essay argues that Buddhist philosophy is fundamentally different from the ideological frameworks of Chaturvarnya (the four-fold caste system) and Brahmanism. While Brahmanism is associated with violence and annihilation, Buddhist thought is rooted in fraternity and peace. The essay highlights the achievements of Ashoka and other rulers in India who embraced Buddhist principles.

It points out the essential differences between Dharmasastra (Hindu legal/religious texts) and Dhammasasana (Buddhist teachings). As noted, “Buddhist Dhamma is not the Dharma of the Hindutva order based on Varnaashrama Dharma. Rather, it is an ethical framework grounded in social equality, co-existence, non-violence, public welfare, and compassion toward all living beings” (2022:106).

While Dharmaśāstras interpret Rajadharma (duty of the ruler) through the lens of Varnaashrama Dharma, legitimizing social divisions, Buddhist texts make no such references to caste or hierarchical divisions.

The thesis identifies the model of governance found in Buddhist perspectives as rooted in the Gana-gotra (clan-republic) system.The Buddha’s formation of the Sangha was inspired by this republican structure.Over time, these republics evolved into larger Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms).The Brahmins, however, had little regard for such republican states and they are barely mentioned in Brahminical texts. In these Gana republics, it was the shramanas (renunciant philosophers like Buddhists and Jains), not the Brahmins, who held greater influence.

Brahmins feared that as states expanded into Mahajanapadas, their own dominance would wane.They thus attempted to position themselves within the growing state machinery as ministers, advisors (sachiv), officials (amatya), council members (parshad), and courtiers (sabhyas).

Texts like the Arthashastra and Manusmriti became strategic tools in plans to attack or undermine these republican clan territories. The essay notes that even revisions of the Mahabharata align with Manu’s legacy.

Quoting from the source, “Kautilya’s Arthashastra is filled with vile strategies to create internal unrest and destroy the Gana-gotra republics. These include infiltrating their assemblies with spies, turning clan elders against each other through praise and insult, sowing hatred by spreading rumors about tribal chiefs in taverns and brothels, and using women as sexual instruments to divide and weaken their leadership. Such ruthless tactics formed the basis of an entirely different political culture.” (2022:116)

While the Manusmriti portrays the Kshatriya as a subordinate instrument under Brahminical authority, the Arthashastra develops strategies to turn the Kshatriya himself into a Brahminized ruler, thus establishing Brahminical supremacy through more covert means.

India’s authoritative historical tradition begins with Emperor Ashoka, who ruled based on Buddhist principles. Ashoka was the third emperor of the Maurya dynasty, ruling roughly 250 years after the time of the Buddha. He conceived of social ethics as a political ideal and implemented it as state policy. During his reign, there was no restriction on other religious beliefs—Brahmins too received due respect. Ashoka moved away from Vedic sacrifices and rituals and instead focused on acts filled with compassion and empathy. It’s not a wonder then how Ashoka’s political history is forgotten. Emperor Ashoka laid the foundation for India’s pluralist legacy. In Ashoka’s edicts there is no reference to varna or caste. He initiated welfare policies that included organizing women and ensuring protection for their livelihoods. The state provided employment to widows, the impoverished, abandoned wives, elderly sex workers, and other marginalized groups. In the same way, Ashok’s was a welfare state that gave employment to poor women, widows, divorcees, old prostitutes etc. Ashoka died in BC 232. He ruled for 37 years. It is important for any ruler to be intelligent and have a legal social perspective. Ashoka who started social justice as a national policy stands as a unique personality in world history. Ashoka is a strong model of the secular tradition of India. The rulers after him were not able to emulate this.

After the fall of the Maurya empire, North India was attacked by foreigners from China and Central Asia. This is followed by the Sunga dynasty, which sabotaged the Buddhist tradition with military torture. This period saw the return of Brahmin supremacy. The Gupta period, which followed, gave even more strength to Brahminism. The Gupta kings took care to build up the Hindu culture and banned anti-Brahmin sentiments. The peasantry and lower classes were coerced into labor to establish agrarian villages, often through force. Brahmins were granted increased authority and privileges during this time.

(to be continued)

Translated by Latha Karuthedath.