The End of Hindutva Hegemony: A Spiritual Rebellion of the Backward

The history of the BJP’s growth is also the story of the self-destruction of backward-class political assertion. From the late 1970s to the 1990s, when anti-caste and reservation-friendly socialist politics gained momentum, this assertion was gradually depoliticized and absorbed into the Hindutva fold. Ashok Kumar V. investigates how the BJP despite being an ideologically upper-caste political party managed to expand and flourish in a country where nearly 60 percent of the population belongs to the backward classes or OBCs.

13 Minutes Read

The Other Backward Classes (OBCs), who comprise roughly 60% of India’s population, include a compilation of approximately 3,800 castes. Within the framework of the Chaturvarnya system, they are traditionally positioned at the fourth stage of the caste hierarchy, known as the Shudras. If counted separately, their population would make them the third largest in the world, after India and China. Positioned between the upper and lower layers, they help perpetuate the caste system by passing down the torment of discrimination from above to the lower layers. However, one significant chapter of Indian social change can be seen in the rise of the OBCs against caste oppression, both before and after independence.

Backward Class: North and South

The first stage of the OBCs’ rise consisted of local struggles against caste domination in the Bombay and Madras Presidencies, occurring before independence. The enduring cultural capital of the OBCs lay in the organised agitations of the period for civil rights—abolition of untouchability, access to education and government jobs, and participation in governance—drawing inspiration from the teachings of Mahatma Phule, Savitribai Phule, Ramaswamy Naicker, and Sree Narayana Guru. The social awakening that historically emerged through agitations against caste oppression remains indispensable today in resisting the advance of the BJP’s Hindutva politics in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

During British rule, no major backward-class movement arose in northern India. One reason for this absence was that the social reform initiatives that began in Bengal were led primarily by college-educated upper-caste elites who drew inspiration from British intellectuals. Consequently, movements such as the Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj did not seriously address the abolition of caste or the upliftment of the lower classes, nor did they seek to cultivate self-consciousness among them. The main concern of these elite Hindu reformist intellectuals was relatively superficial: to recast upper-caste traditions into forms suited to the times. Moreover, they urged Hindu society to seek inspiration in an imagined golden age of the past, celebrating tales of the ancient holy land of the Vedas and Upanishads—an intentional historical construction shaped by British colonial scholars such as William Jones and Max Müller. Their cultural engagement amounted to a recipe for a Hindu society that selectively blended ancient traditions with modern ideas, while leaving caste hierarchies largely untouched.

Secondly, when Ambedkar challenged the myth of ancient glory—exposing its foundations in casteism through his vast knowledge, rational thinking, and vision of fraternity—the leadership of the independence movement found little value in joining him to address the caste question. Most leaders of the movement were under the illusion that the caste-based social order could be reformed after independence. Unlike in South India, the backward-class uprising in the North was stalled because social reforms against casteism were postponed after independence, as priority was given to achieving political freedom from British rule. Consequently, in the North, no significant section of the backward classes was able to take advantage of the educational institutions, public-sector opportunities, and reservation policies that emerged after independence.

(After independence, the Nehru government prioritised education and the development of public-sector industries with a socialist orientation, which in turn opened new avenues of opportunity for the OBCs in the south. A few among them were able to enter schools and colleges through state government reservation policies and fee concessions, and in time, many secured jobs in public offices, becoming part of the government itself.)

Thirdly, although some OBCs in the North were relatively wealthy landowning farmers, they lacked access to education and awareness needed to challenge caste discrimination and did not develop a sense of collective self-respect through this process. Therefore, the widespread acceptance of granting equal rights and reservation benefits to society did not take root in the North.

A Strange Alliance: The Pro-Reservationists and the Anti-Reservationists

The purpose of reservations in education, employment, and politics is not merely administrative but fundamentally aimed at empowering backward communities, ensuring their meaningful participation in the governance of democratic India, and advancing social justice. Since caste has historically functioned in India as a tool for monopolising power and centralising authority, the only effective way to ensure equal participation in democracy is to guarantee reservations for all marginalised and oppressed communities. The objective of reservation is not merely the economic progress of the backward classes; rather, it is to eradicate their socially oppressed status by ensuring their participation in governance through education, employment, and politics. It serves as an antidote to the social disabilities imposed by casteism. Since caste-based discrimination and oppression could not be eradicated within a short period, the Constituent Assembly did not impose any fixed time limit for the continuation of reservation.

As part of the constitutional ideal of building a meaningful democracy, the central government appointed the Kaka Kalelkar Commission in 1953 to recommend the extension of reservations to the backward classes in addition to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Although the report was submitted in the same year, the Nehru government set it aside without taking any further action. This was because strong opposition to reservations arose not only from Hindutva-oriented parties such as the Hindu Mahasabha and the Jana Sangh, but also from within the Congress itself.

In opposition to caste oppression, the OBCs in North India aligned with socialist politics when Jayaprakash Narayan and Ram Manohar Lohia—who had long opposed the Congress’s right-wing policies since the 1930s—helped form the Socialist Party, which combined Gandhian ideas of decentralisation with Marxian concepts of equality. However, despite holding fundamentally different positions on caste issues compared to the Jana Sangh, the Socialist Party formed an alliance with them to defeat the Congress in the 1967 Uttar Pradesh election. As a result, a non-Congress ministry was installed for the first time in India. The OBC votes shifted to the anti-caste socialists, which helped the caste-Hindu–socialist alliance come to power in India.

The successful repetition of this alliance strategy at the national level led to the formation of the Janata Party—a pragmatic coalition of socialists and right-wing Hindu groups after the Emergency, enabling a non-Congress government to assume power in 1977 despite stark ideological differences among its members. Thus, Hindutva, represented by the Jana Sangh since 1951 and aiming to emerge as a national force against the Congress—metamorphosed into the Janata Party, a strategic step towards the vision of a Hindu Rashtra. In other words, the upper-caste votes for the Congress and the backward-class votes for the socialists consolidated this unusual political alliance, creating a partnership that was ideologically tense but electorally effective.

However, this transformation of the Jana Sangh into the Janata Party ultimately proved to be a setback for the socialists. When Janata Party Chief Minister Karpoori Thakur, himself from the barber caste within the OBCs, introduced OBC reservations (Mungeri Lal Commission Report) in Bihar in 1979, the first such measure in India, the student unions aligned with the Jana Sangh, A.B.V.P., launched an anti-reservation agitation.

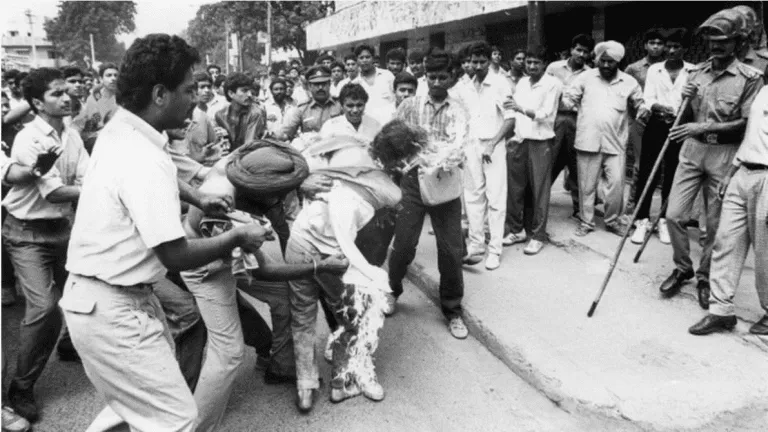

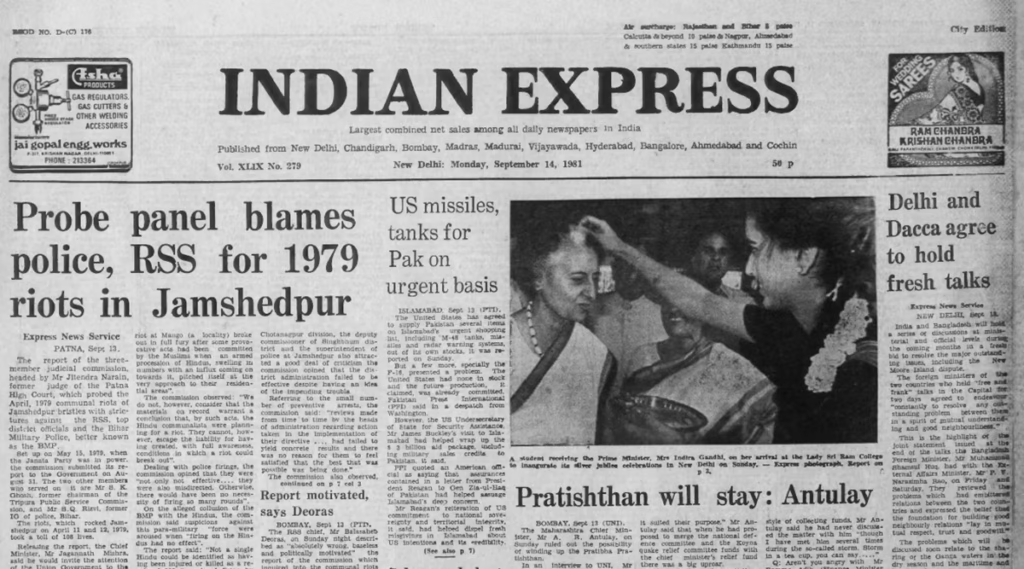

In response to the agitation, on 21 March 1979, the Janata government appointed a five-member commission to initiate steps for implementing OBC reservations at the central level. By appointing B.P. Mandal—a minister in the Bihar government and an OBC leader as chairman of the commission, the socialists sought to counter the encroachment of Hindutva politics. However, on 11 April of the following month, a communal riot broke out in Jamshedpur, Bihar, resulting in the deaths of 108 people and causing extensive damage. Consequently, the Jana Sangh demanded the removal of Karpoori Thakur from the post of Chief Minister. In his place, a Dalit MLA, Sunder Das, was elevated to the position, which in turn triggered a split within the socialist ranks. At last, by introducing economic reservations for the upper castes within the OBC quota, the very foundation of the reservation system was subverted in Bihar.

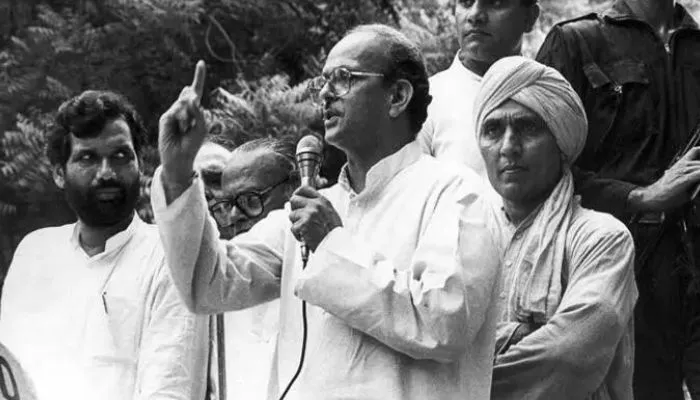

The panel appointed by the Janata Party to investigate the Jamshedpur riot found that the RSS had played a significant role in instigating the violence. The enquiry commission appointed by the state government also pointed this out later (Report of the three-member commission of inquiry, headed by Jitendra Narain). In consequence, the Janata Party parliamentary committee asked the Jana Sangh leaders to cancel their membership in the RSS (dual membership). This was because, as a prerequisite for their inclusion into the Janata Party, the leadership of the Jana Sangh had already promised the Janata Party leaders, including Jayaprakash Narayan, that they would relinquish their dual membership with the RSS and that they would give up communal politics if the Janata Party came to power. However, the Jana Sangh eventually deviated from its promise. As a result, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani resigned from their positions in the central ministry, and the Jana Sangh faction withdrew from the Janata Party altogether. This split led to the collapse of the Janata government. Subsequently, in 1980, the Jana Sangh reorganised itself as the Bharatiya Janata Party.

The electoral alliance of 1989 between V.P. Singh’s Janata Dal and the BJP once again created, much like in 1977, a golden opportunity for the BJP to expand its reach among backward class voters. Benefiting from this alliance, the BJP secured 85 seats in 1989, a dramatic rise from just two seats in 1984. Conversely, the Janata Dal won 124 seats in 1989. In 1990, seeking to prevent the consolidation of OBC votes in favour of the BJP, Prime Minister V.P. Singh swiftly announced the implementation of the Mandal Commission report. Although the BJP had also promised to implement the Mandal Commission report in its 1989 election manifesto, when Rajiv Goswami attempted self-immolation in protest against the report’s implementation, L.K. Advani visited him in hospital. Subsequently, across North India, waves of anti-reservation protests erupted, marked by atrocities and numerous acts of self-immolation. If a communal riot had shaken Jamshedpur a decade earlier, now an even sharper weapon was drawn to resist the Mandal recommendations.

In the following month, L.K. Advani launched his Rath Yatra (chariot journey) to mobilise the masses for the construction of a Ram temple at Ayodhya all over North India. He sought to quell the growing urgency for backward caste reservations by invoking Hindu unity, using anti-Muslim rhetoric as a rallying call. Moreover, in response to the V.P. Singh government’s attempt to prevent the Rath Yatra, the BJP withdrew its support from the central government, leading to its collapse. In the subsequent election, the BJP’s seat count rose from 85 to 120, while the Janata Dal’s seats fell from 124 to 59. The result was that the BJP, for the first time in India, had emerged as the chief opposition party in Parliament.

If the upper caste representation in Parliament in the 1970s was above 50%, in the same period the OBC representation was roughly 10%. The number of OBC MPs rose from 11% in 1984 to 20% in the beginning of the 1990s. Along with that, the number of upper caste MPs diminished from 47% in 1984 to 40% in the 1990s. This means that socialist politics and its Mandal reservation raised the participation of the OBCs in the government. However, when the BJP rose to power in 2014, the number of upper caste MPs again rose to 44.5%. Conversely, OBC MPs had been reduced to 20%.

In the 1970s, the representation of the upper castes in Parliament was above 50%, while the Other Backward Classes accounted for barely 10%. By 1984, OBC MPs constituted around 11%, and their share rose to about 20% by the early 1990s. During the same period, the representation of upper-caste MPs declined from 47% in 1984 to around 40% in the 1990s. This shift reflected the impact of socialist politics and the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s reservation policies, which significantly enhanced the political participation of OBCs.

BJP leader and Rajya Sabha Speaker Om Birla, an MP from Rajasthan, once remarked, “All other castes are led by the Brahmins, who are regarded as highly revered people, considered holy and noble by birth. Similarly, when Yogi Adityanath moved into the Chief Minister’s official residence—previously occupied by Akhilesh Yadav, Mayawati, and Mulayam Singh—he first had it ritually purified by priests through elaborate religious ceremonies.”

The Limitations of Reservation Politics

From the late 1970s to the 1990s, the backward classes advanced politically during a phase of heightened caste resistance and pro-reservation socialist mobilisation. The BJP’s expansion can be read as the co-option of this OBC progress into the framework of Hindutva politics, achieved by depoliticising and eroding the distinct identity of the backward classes. The BJP recognised that the restoration of upper-caste dominance was impossible without subordinating the backward classes—who make up more than 52% of India’s population, roughly 650 million—to its political authority. In 2009, the BJP secured only 22% of the OBC vote, with regional parties drawing around 42%. A decade later, in the 2019 election, the BJP’s OBC support had doubled to 44%, while the regional parties’ share dropped to 27%. This political success of Hindutva was rooted in a dual strategy: instilling economic resentment among the most depressed OBC communities towards the dominant Yadavs within the OBC category, while simultaneously inciting religious hostility towards Muslims. The same process of assimilating the most depressed classes into the Hindutva fold has been systematically extended to Dalit society as well.

The BJP organised an OBC Morcha for the first time in India’s history, to undermine the dominance of the wealthy Yadavs, who had long been the most influential OBC group in the politics of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and expanding its own political control across other regions. In addition, the party instituted an inquiry commission under retired Justice G. Rohini to identify the affluent sections among the OBCs, ostensibly to ensure that reservation benefits reached only the economically weaker groups. This calculated manoeuvre proved effective in reinforcing the existing caste hierarchy of power: it portrayed the backward classes as mutually antagonistic, kept caste divisions alive within them, and ultimately aligned them as subservient supporters of Hindutva ideology and the violence of the upper castes.

The OBCs, who occupy the lower rungs of the caste hierarchy alongside Dalits and Adivasis, sustain the upper classes—constituting barely ten percent of India’s population—through their labour in a wide range of strenuous occupations such as washing, fishing, farming, artisanal work, and barbering. Brahmanism portrays birth into a labouring caste as a divine punishment, and therefore regards those engaged in manual labour—cleaning, washing, or other physical tasks—as belonging to the lower castes. The Shudras remain subordinates within this Brahmanical order, which defines human worth by birth and sanctifies inequality. As Kancha Ilaiah observes, the Shudras have seldom awakened to claim equality; nor have they granted Dalits an equal place alongside themselves. What the Brahmin priest declares is accepted by them as the word of God. Thus, the Shudra ideology is one rooted in production and hard work, yet it is deeply enveloped in an inferiority complex, ignorance, and a lack of spiritual and social consciousness.

The social, mental, and spiritual subordination that envelops the so-called untouchable communities from birth, rooted in Brahmanical domination, cannot be dismantled merely through the political power attained by means of reservation. This is because reservation transfers power to individuals within a community, without ensuring that these individuals represent or safeguard the collective interests of their group. For instance, even though Narendra Modi, an OBC, occupies the position of Prime Minister, the structural hierarchy remains intact: upper castes have been brought within the ambit of reservation, while the rights of the genuinely backward castes are being eroded through measures such as the appointment of the OBC Commission, which seeks to redefine and minimise their share.

The upper-caste intelligentsia has succeeded in turning the backward classes into their political instruments by co-opting a few OBC leaders through the selective distribution of positions and power. The reservation system has, in effect, mocked the very purpose it was meant to serve, as many individuals from the OBC communities who have gained education or employment through reservation now enter the ideological fold of Hindutva—an ideology that has consistently denied the interests of their class. Even though leaders from the Yadav community have ruled Bihar and Uttar Pradesh for nearly three decades, is the condition of the majority of the backward classes there still deeply pathetic? Is the BJP trying to introduce reservation only for the extremely poor among the OBCs by taking advantage of this situation?

The Spirituality of Emancipatory Democracy

Still, why has the BJP been unable to penetrate the backward-caste base in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, unlike in North India? The reason is that, unlike in the northern states, the backward classes of this region had already undergone a degree of spiritual awakening, even if only partially, that weakened the hold of Brahmanical domination. It would be more appropriate here to recall Kancha Ilaiah’s observation that, although the Shudras have gained access to power through education and employment, their mental and spiritual subordination has not yet been removed. Shudras cannot liberate themselves from the layers of Brahmanical ideology imposed upon them.

However, he overlooked the uniquely significant spiritual resurgence that emerged among the backward classes of Kerala in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Saiva Prakasa Sabha founded by Manonmaniam Sundaram Pillai, Sree Narayana Guru’s consecration of the Aruvippuram idol, Poykayil Sree Kumara Gurudevan’s Prathyaksha Raksha Daiva Sabha, and the Atma Vidya Sangam founded by Vagbhatananda—all these movements sought to reclaim the spiritual power of the backward classes by fundamentally challenging the Brahmanical monopoly over spiritual authority. What happened in Kerala was a cultural revolution aimed at attaining spiritual power, which restored the identity of the backward classes before they began their struggle for political power.

Kancha Ilaiah wrote that spiritual power has the potential to become a social force across the country, whereas political power cannot achieve the same. Political power cannot achieve the same. Political power, he observes, merely coordinates people around struggles in the economic and political spheres of daily life, while spiritual power and philosophy offer profound ideas that unite people at a deeper level. Therefore, without attaining spiritual power, the Shudras cannot exercise authentic control over society. They still lack the courage to challenge the spiritual world created by Brahmanical writers through knowledge and writing of their own.

Kancha Ilaiah’s reflections recall the historical significance of the southern spiritual leaders who, through their pursuit of knowledge and reflective thought, reinstated the spiritual power of the marginalised and thereby challenged the intellectual authority of even the most erudite Brahmins. Struggles driven solely by the pursuit of power, without awakening the self-consciousness of the Shudras, cannot free the marginalised from the ideological bondage of the ruling classes. As a result, both their inherited reverence for the Brahmins and their contempt towards those placed below them in the social hierarchy persist unchanged. In the absence of spiritual self-awareness, representatives of the backward classes who attain higher positions through reservation frequently adopt the culture of the dominant classes, transforming into steadfast protectors of the caste hierarchy itself.Hence, to safeguard the backward classes from continuing self-subjugation under Hindutva politics, it is imperative that they reclaim the spiritual power they once began to cultivate but left incomplete. Only then can they resist the treacherous manoeuvres that organised the OBC morcha to neutralise the theory of reservation. They can recognise the limitations of reservation while still firmly defending it, understanding that political equality does not automatically translate into spiritual equality.

Equality at the polling booth offers no guarantee of equality before temples or access to salvation. The renewal of self-consciousness among the marginalised is therefore a prerequisite for the prosperity of the country and for establishing a system of spirituality rooted in genuine democracy.In a fragmented society corrupted by casteism, equality can be realised only when the marginalised regain spiritual power. The spiritual power of the oppressed is, in itself, a transformative force that reconstitutes the traditional edifice of upper-caste spirituality and opens the path towards an emancipatory democracy. This spirituality of liberation, emerging from the grassroots, reshapes every sphere of life—shifting it from the market-driven faith rooted in upper-class consumer desire to an inner force of simplicity and truth. Above all, it dissolves the long-standing division between the material and the spiritual.

Reference

1. Kaka Kalelkar Commission 1953

2. Mungeri Lal Commission Report 1979

3. Report of the three members commission of inquiry: headed by Jithendra Narain

4. Jayaprakash Narayan: An Idealist Betrayed, M.G. Devasahayam

5. What is left of the Mandal moment, politically and socially, now? Christopher Jaffrelot. indianexpress.com. August 22,2020

5.Rise of Hindutva has enabled a counter revolution against Mandal’s gains. Christopher Jaffrelot.indianexpress.com. February 10,2021

6. The Shudra Civilization. Kancha llaiah Shepherd. Mainstream.