The DNA Speaks: A Scientific Challenge to Hindutva’s Sacred Geography

This article, the second in a series reviewing Tony Joseph’s Early Indians, explores how cutting-edge genetic research, particularly ancient DNA studies, breaks the ideological deadlock surrounding India’s origins. It explains how population genetics provides clear evidence for multiple waves of migration into the subcontinent, beginning with the First Indians from Africa, followed by Iranian agriculturalists, and later, Indo-European speakers from the Central Asian Steppe. These scientific findings directly challenge Hindutva notions of a pure, ancestral pithrubhumi and punyabhumi, revealing instead a deeply mixed and migratory past that centers Adivasi communities as the region’s earliest inhabitants and exposes the caste system as a relatively recent social construction.

10 Minutes Read

Part 2

The Impasse and the Scientific Witness

By the early 21st century, the debate had reached a toxic impasse. Archaeologists, linguists, and historians argued in circles, with each side interpreting the same evidence through its predetermined ideological lens. The debate was trapped in a hermeneutic circle of its own making. It was into this deadlock that a new, independent, and powerfully objective witness was summoned: genetics. The “revolutionary power of population genetics” (Joseph 12), particularly the analysis of ancient DNA (aDNA), provided a direct way to test the demographic claims of both theories. By analysing the DNA of thousands of modern Indians and, crucially, comparing it with a growing library of aDNA from archaeological remains across Eurasia, scientists could trace ancestral lineages, map ancient migrations, and date the timing of population mixing with unprecedented precision. This new science, as Tony Joseph so skillfully demonstrates, was not beholden to political agendas or ancient texts. It simply followed the data, and in doing so, it provided the key to unlock the stalemate and write a new, more truthful, and far more intricate story of India’s origins.

The Scientific Counter-Narrative

At the heart of Early Indians is a compelling narrative built not on ideology but on a synthesis of evidence from population genetics, archaeology, and linguistics. Joseph masterfully structures this story as a four-act play, each act representing a major wave of migration and synthesis that layered itself upon the last, creating the complex human tapestry of the subcontinent.

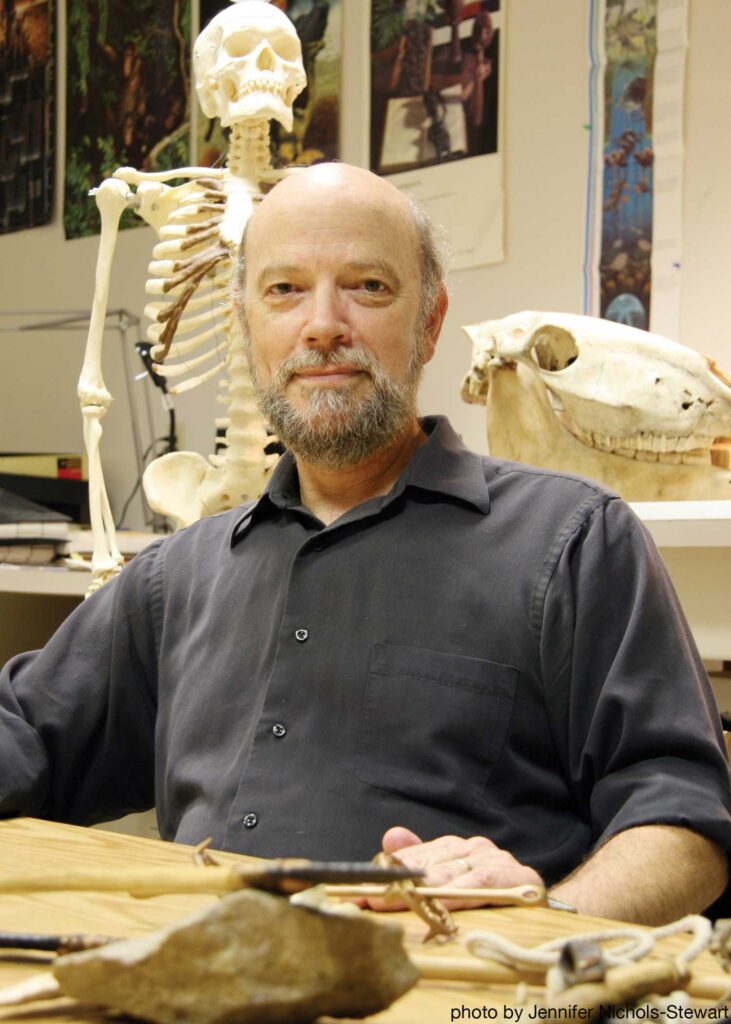

Before delving into the four acts, it is essential to understand the scientific tools Tony Joseph employs. The revolution in population genetics rests on the ability to read the history recorded in our DNA. Two key types of DNA are crucial. First is mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is passed down exclusively from mother to child, tracing an unbroken maternal line deep into the past. Second is the Y-chromosome, passed down only from father to son, revealing the history of paternal lineages. Specific mutations, or markers, on these DNA strands create distinct lineages called “haplogroups.” By tracking the geographic distribution and age of these haplogroups, geneticists like David Reich at Harvard University, whose work forms a cornerstone of Tony Joseph’s synthesis, can reconstruct ancient population movements (Reich, p.10-15). Furthermore, the analysis of the entire genome (autosomal DNA) allows scientists to determine the percentage of ancestry an individual or a population derives from different ancient ancestral groups, and even to estimate when different populations stopped mixing with one another. It is this “unambiguous” genetic data that forms the evidentiary spine of Tony Joseph’s narrative, a narrative that begins, for all humanity, in Africa.

Act I: The Bedrock – The First Indians (c. 65,000 BCE)

The story of the Indian people begins with the first act of the larger human story: the “Out of Africa” migration. Tony Joseph establishes that the very first modern humans to set foot on the subcontinent arrived around 65,000 years ago (Joseph, p.45). These were pioneers who likely travelled along the southern coast of Asia, a determined band of hunter-gatherers who, for tens of thousands of years, were the sole human inhabitants of India. Tony Joseph terms them, appropriately, the “First Indians.”

Their genetic footprint is the foundational layer, the “bedrock” of the Indian population. In Tony Joseph’s famous analogy, they are the “base of the pizza,” upon which all subsequent population layers, or “toppings,” were built. Today, their ancestry is most purely preserved in isolated tribal populations, such as the Onge and Jarawa of the Andaman Islands, whose genes provide a direct window into this deep past. On the mainland, Adivasi (tribal) communities carry the highest proportions of First Indian ancestry, traced through the ancient mtDNA haplogroup M and its many subclades, which are ubiquitous across the subcontinent.

The hermeneutical significance of placing this group first is profound. Joseph immediately and decisively re-centres the narrative of indigeneity. In one stroke, he demolishes any historical or political framework that seeks to sideline, diminish, or patronize Adivasi peoples as “fringe” or “primitive.” Genetically, they are the subcontinent’s most deep-rooted inhabitants. The story of India, Joseph insists, must begin with them. Every other group to set foot in India, without exception, is a later arrival. This establishes the book’s central, unifying theme: migration, not static isolation, is the fundamental human story.

Act II: The Genesis of Civilization – The Harappan Synthesis (c. 7000–1900 BCE)

The second major event in India’s demographic history was not a dramatic invasion but a slow, transformative diffusion of people and agricultural technology from the west. Beginning around 7000 BCE, early agriculturalists from the Zagros mountains of what is now Iran and the Fertile Crescent began migrating eastwards into the subcontinent (Joseph, p.65). Crucially, these migrants did not replace the First Indians. The genetic record is clear: they mixed with the pre-existing hunter-gatherer population.

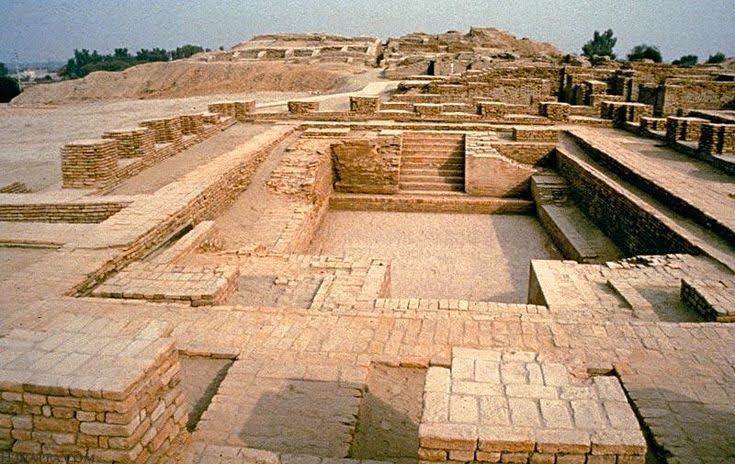

It was this vibrant, mixed population—a blend of Iranian farmer ancestry and First Indian hunter-gatherer ancestry—that went on to create the magnificent Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), also known as the Harappan Civilization, around 3000 BCE. This civilization, one of the world’s first great urban cultures, boasted sophisticated city planning, advanced sanitation, extensive trade networks reaching Mesopotamia, and a unique, still-undeciphered script. This is a critical intervention in the historical debate. Joseph shows that the Harappans, the architects of this brilliant civilization, were not a single, “pure” race but a cosmopolitan mix.

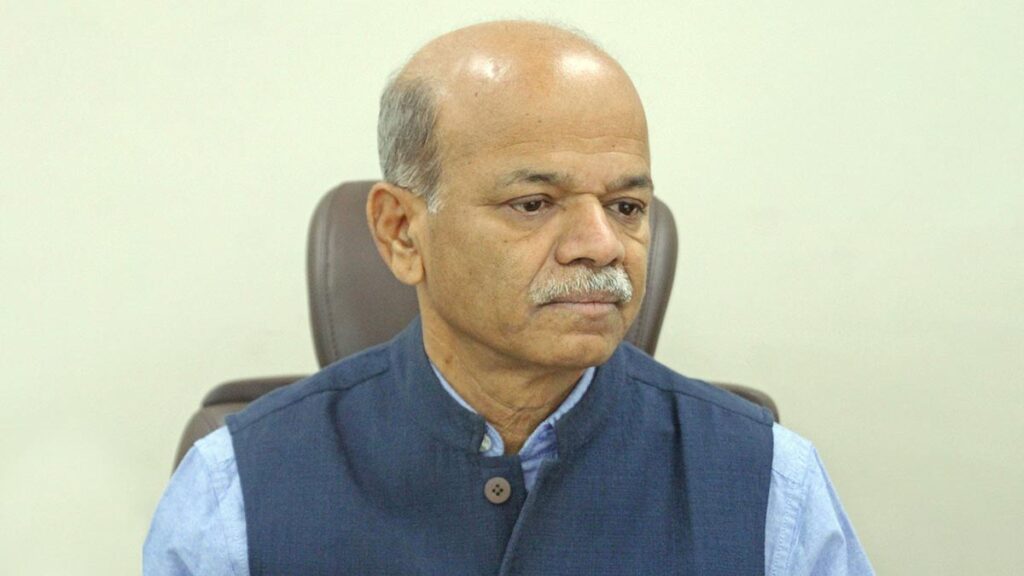

The definitive evidence comes from the analysis of ancient DNA from a Harappan individual at the site of Rakhigarhi, published by Vasant Shinde et al. (Prof. Vasant Shivram Shinde) in the journal Cell in 2019. The landmark study of the Rakhigarhi genome revealed two crucial facts. First, it showed a mixture of ancestry related to ancient Iranian farmers and ancestry from the First Indians, precisely as Joseph’s model predicts. Second, and even more significantly, it showed a complete and total absence of any ancestry from the Central Asian Steppe (Shinde et al. p.729). This single finding proves that the Harappans and the Steppe pastoralists (the carriers of early Indo-European language) were genetically distinct populations, delivering a fatal blow to the OIT claim that the Indus Valley Civilization was itself “Vedic.” The chronological and genetic separation is undeniable.

Act III: The Steppe Connection – A New Wave of Migration (c. 2000–1500 BCE)

This is the most politically explosive act of the Indian origin story, as it directly addresses the “Aryan” question. With meticulous care, Joseph marshals overwhelming evidence to demonstrate that a demographically significant migration of Indo-European language speakers occurred from the Central Asian steppes (modern-day Kazakhstan) into India, beginning around 2000 BCE. This period coincides with the decline of the Harappan cities, likely exacerbated by climate change and the drying up of major river systems.

Joseph is careful to dismantle the old, colonial-era “Aryan Invasion Theory” (AIT), with its connotations of a violent, racially-motivated conquest. Instead, he supports a more nuanced “Aryan Migration Theory” (AMT), envisioning a gradual influx of people, culture, and language over several centuries. The genetic data is unequivocal. The landmark 2019 paper in Science by Vagheesh Narasimhan, David Reich, et al., which analysed 523 ancient individuals, demonstrates a clear and sudden influx of a new ancestral component, termed “Steppe pastoralist ancestry,” into North India during this period. This ancestry is most strongly associated with the Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a (specifically the Z93 subclade), which is common in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and appears in high frequencies in North India today, especially among Brahmin and other upper-caste communities, but is conspicuously absent in aDNA from Harappan sites (Narasimhan et al.).

The evidence also points to this being a “male-driven migration,” as the Steppe genetic signature is far stronger in the paternal line (Y-chromosome) than in the maternal line (mtDNA) across the subcontinent. This suggests a pattern in which migrating Steppe men mixed with local women of Harappan and Early Indian descent (Joseph, p.178). These migrants brought with them the key cultural components that would define the Vedic Age: an early form of the Sanskrit language, a patriarchal social structure, the domesticated horse and the spoked-wheel chariot, and the fire-and-ritual-centrism religion that would eventually be codified in the Rigveda. As the historian David Anthony argues in The Horse, the Wheel, and Language, these innovations gave Indo-European speakers a significant cultural and military advantage. This argument directly and decisively refutes the “Out of India” theory, for which there is simply no scientific explanation for the sudden appearance of large-scale Steppe DNA in the Indian gene pool around this specific time.

Act IV: The Making of Modern Indians – The Great Admixture and the Great Wall (c. 2000 BCE – 100 CE and beyond)

The final act of this ancient drama is the story of how these distinct ancestral groups blended to create the populations of modern India. Following the arrival of the Steppe pastoralists, the subcontinent became a veritable “melting pot.” The newly arrived Steppe people began to mix extensively with the existing Harappan-descended population (itself a mix of First Indians and Zagros farmers). This three-way mixture created the group that geneticists call the “Ancestral North Indians” (ANI). The ANI, therefore, are a composite of First Indian, Iranian farmer, and Steppe pastoralist ancestries. In peninsular India, the Harappan-descended population mixed more with the local First Indian groups, with little or no Steppe input, creating the “Ancestral South Indians” (ASI). It is crucial to understand, as Joseph clarifies, that ANI and ASI are not discrete, ancient populations but rather labels for the opposite ends of a genetic gradient, or cline, that was formed through this admixture process.

For nearly two millennia, from roughly 2000 BCE to 100 CE, these two large population groups—the ANI and ASI—mixed freely with each other. The result is that today, virtually every single person on the Indian subcontinent is a mix of ANI and ASI ancestries, just in varying proportions. This is visible as a genetic gradient that runs from north to south and west to east. North Indians and upper castes tend to have a higher proportion of ANI ancestry (and thus more Steppe ancestry), while South Indians and lower castes have a higher proportion of ASI ancestry (and thus more First Indian ancestry).

Then, around 100 CE (or 1900 years ago), the genetic data revealed that something dramatic and profound happened. The mixing stopped. Drawing on a 2013 study by Priya Moorjani, Reich, and others in The American Journal of Human Genetics, Joseph highlights this startling genetic discovery. As he powerfully puts it, a “Great Wall” went up within Indian society, separating different groups from each other and preventing intermarriage (Joseph, p.221). This wall was the caste system. The practice of strict endogamy—marrying only within one’s caste group—became rigid and widespread. This genetic data stunningly corroborates what social historians have long argued about the solidification of the caste system, likely codified in texts like the Manusmriti around this period. This endogamy effectively “froze the population structure in time,” creating thousands of distinct genetic clusters that correspond to modern caste and community groups (Moorjani et al, p.422). This finding is a devastating blow to arguments that the caste system is an immutable, “timeless” feature of Indian society; genetically, its rigid enforcement is a relatively recent historical phenomenon.

Cover Photo by Vasant Shinde DCPGRI

(to be continued)