Myth and Nation: Unpacking the Ideological Roots of Hindutva Nationhood

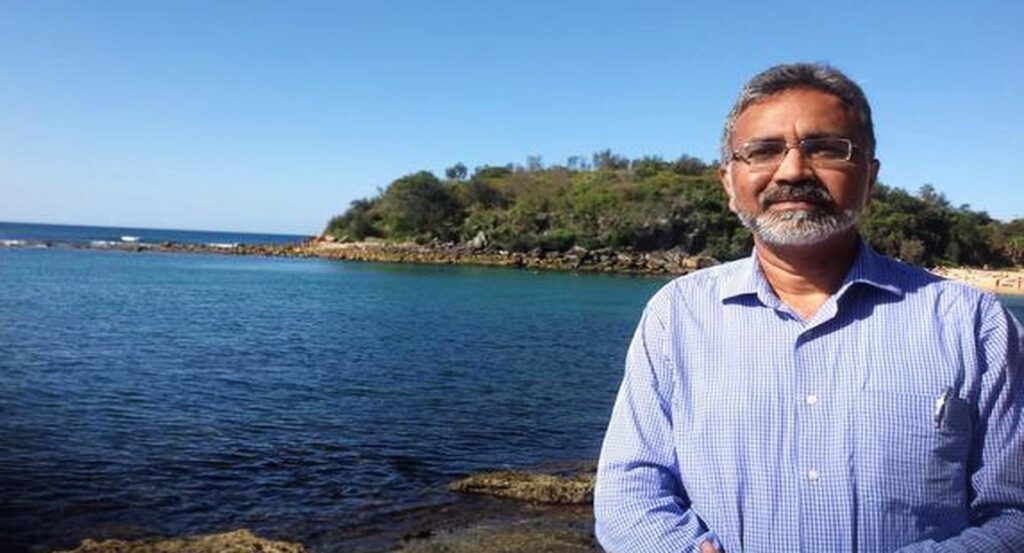

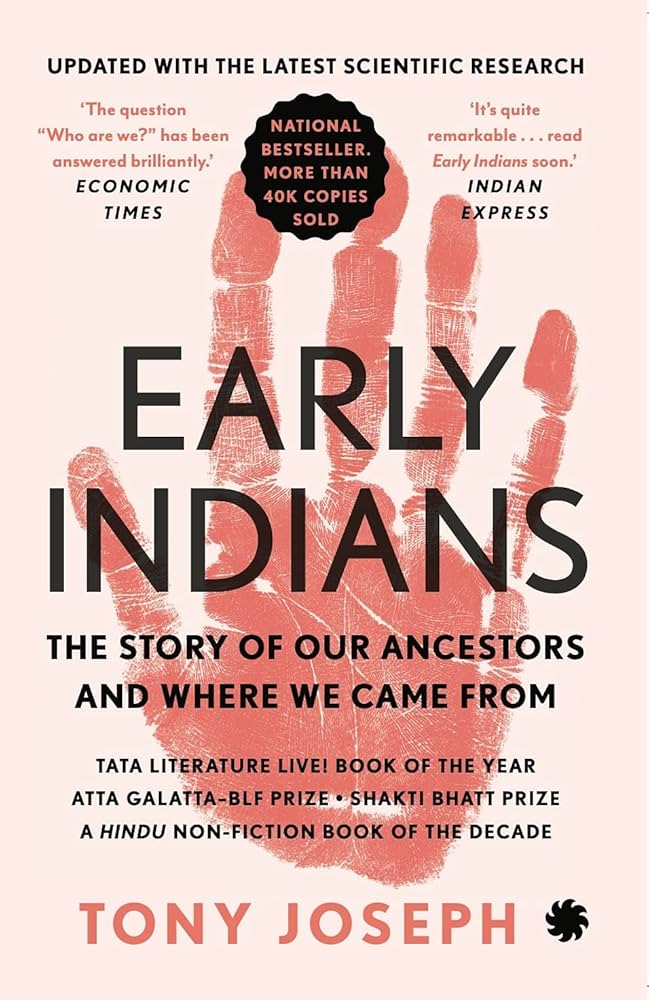

Book review of Tony Joseph’s Early Indians: A Scientific Refutation of Hindutva concepts of Pithrubhumi and Punyabhumi is a series of articles by V.A. Mohamad Ashrof that offers a comprehensive refutation of the pitrubhumi and punyabhumi concepts through a hermeneutical analysis of the scientific evidence compellingly synthesized in Tony Joseph’s seminal work, Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From. Joseph’s book, which brings together decades of groundbreaking research in population genetics, archaeogenetics, archaeology, and linguistics, presents a radically different account of Indian origins—one not of stasis and purity, but of continuous migration, profound admixture, and relentless cultural synthesis.

10 Minutes Read

Part 1

The narratives a nation tells about its origins are foundational to its identity. They shape its sense of self, its political culture, and its definition of belonging. In the context of modern India, two of the most potent and politically charged concepts shaping these narratives are pithrubhumi (fatherland or ancestral land) and punyabhumi (holy land). When fused, these ideas posit an exclusive, primordial, and sacred connection between the Indian subcontinent and a specific ethno-religious community, providing the ideological bedrock for a powerful form of ethno-nationalism. This framework asserts that authentic Indian identity is reserved for those whose ancestry and faith are both indigenous to the land, thereby creating a hierarchy of citizenship that privileges some and marginalizes others. This ideology, however, rests upon a set of historical and anthropological assumptions about an unbroken lineage, genetic purity, and a static, singular sacredness.

This paper offers a comprehensive refutation of the pithrubhumi and punyabhumi concepts by conducting a hermeneutical analysis of the scientific evidence compellingly synthesized in Tony Joseph’s seminal work, Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From. Joseph’s book, which collates decades of revolutionary research in population genetics, archaeogenetics, archaeology, and linguistics, presents a radically different story of Indian origins—one not of stasis and purity, but of continuous migration, profound admixture, and relentless cultural synthesis. By treating Tony Joseph’s scientific narrative as a historical text, this paper will interpret its findings to systematically dismantle the core tenets of the pithrubhumi and punyabhumi ideology propounded by Hindutva ideology. It will argue that the scientific reality of a multi-source, deeply mixed population renders the notion of an exclusive, primordial fatherland untenable. Similarly, it will demonstrate that the history of a dynamic, layered, and pluralistic spiritual landscape invalidates the claim of a singular, exclusive holy land.

To achieve this, the paper will first delve into the ideological architecture of pithrubhumi and punyabhumi, examining their modern political formulation and deep psychological appeal. Second, it will contextualize Tony Joseph’s work within the century-long historiographical battle between the colonial-era Aryan Invasion Theory and the nationalist Out of India Theory, showing how genetics provided an objective witness to break the stalemate. Third, it will undertake a detailed exploration of the four-act scientific narrative presented in Early Indians, laying out the evidence for the successive waves of migration and admixture that formed the Indian population. Finally, this scientific evidence will be brought to bear directly on the ideological claims, deconstructing them pillar by pillar. Ultimately, this paper contends that embracing the fluid, migratory, and syncretic truth of Indian history, as revealed by science and synthesized by Tony Joseph, is essential for moving beyond exclusionary myths and fostering a more inclusive and historically honest national identity.

The Ideological Architecture of Belonging: Forging a Myth of Origins

To refute pithrubhumi and punyabhumi, one must first understand their modern political architecture and their profound psychological appeal. These are not ancient, immutable truths but specific ideological tools forged in the crucible of 20th-century politics to serve a particular vision of the nation. Their power lies in their ability to conflate geography, ancestry, and faith into a seemingly natural and self-evident definition of nationhood.

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar most famously and explicitly articulates the modern formulation of this dual concept in his 1923 text, Essentials of Hindutva. In his effort to create a cohesive political identity (Hindutva, or Hinduness) that could unite the diverse array of sects, castes, and communities under the Hindu umbrella, Savarkar proposed a powerful, two-pronged definition of belonging. A true member of the Hindu nation, he argued, considers India not only their pithrubhumi but also their punyabhumi. He defines it thus: “A Hindu therefore, is he who feels attachment to the land that extends from Sindhu to Sindhu as the land of his forefathers—his pitribhumi—and who addresses her as his punyabhumi, the land of his religion” (Savarkar, p.45).

This definition was politically brilliant in its simplicity and its exclusionary power. It immediately created a clear in-group—Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, and Sikhs, whose religions originated on the subcontinent—and a perpetual out-group of “others,” namely Indian Muslims and Christians. For these communities, despite potentially having the exact same ancestral roots in the land for centuries, their punyabhumi (Mecca or Jerusalem) lay elsewhere. In Savarkar’s framework, this geographical dislocation of their holy land rendered their national loyalty inherently suspect. He argued that their love was “divided,” making them incomplete citizens. This formulation effectively turned geography into destiny and faith into a litmus test for full membership in the nation, providing the intellectual justification for a hierarchy of belonging that persists in political discourse today.

The Psychological Appeal of Pithrubhumi

The concept of pithrubhumi appeals to a deep and primal human need for rootedness and timeless belonging. It posits the existence of an autochthonous people—a group that supposedly originated in the land itself, with no prior history of migration—from whom the “true” Indians are descended. This myth of an unbroken, unmixed lineage serves to legitimize a claim of primordial ownership over the land, granting cultural and political precedence to the self-defined “original” inhabitants.

This myth creates a simple, heroic narrative that erases the messy, complex, and often inconvenient realities of historical migrations, conquests, and cultural interactions. It replaces a dynamic history with a story of static purity and eternal presence. As the eminent historian Romila Thapar has noted, such “invented traditions” are not organic historical memories but are consciously constructed by selectively reading the past to serve present-day political goals. The goal, in this case, is the creation of a homogenous national identity that can be mobilized for political ends (Thapar, p.34). The pithrubhumi concept provides the emotional and psychological bedrock for this project, offering a sense of security and superiority rooted in the very soil of the nation. It transforms history from a subject of inquiry into an article of faith.

The Sacralisation of Geography in Punyabhumi

Complementing the ethnic claim of pithrubhumi is the theological claim of punyabhumi, which sacralises the geography of the nation-state. It elevates the Indian subcontinent from a mere territory to a uniquely holy landscape, divinely ordained as the stage for the drama of Dharmic religions. This concept draws on ancient and rich Puranic traditions of sacred geography (tirthayatra), which map a spiritual cosmology onto the physical land, imbuing rivers like the Ganga and Yamuna, mountains like the Himalayas, and cities like Varanasi and Ayodhya with profound divine significance (Habib, p.56). This network of sacred sites created a cultural-religious map that unified diverse regions long before the advent of the modern nation-state.

In its modern political usage, however, this expansive cultural concept is weaponized into an exclusionary tool. By defining the land’s sacredness exclusively through a Dharmic (and often, more narrowly, a Brahmanical) lens, it implicitly frames other faiths as foreign intrusions upon a sacred Hindu space. This ideology underpins a worldview where the presence of mosques and churches is seen not as a testament to India’s long and celebrated pluralistic heritage, but as a scar of historical conquest and a mark of cultural impurity. The very existence of these “foreign” holy sites becomes a source of grievance, a symbol of a lost purity that must be reclaimed. Together, pithrubhumi and punyabhumi create a powerful, self-contained ideological system where blood, soil, and faith are fused into a tripartite definition of a narrow, exclusionary, and supposedly primordial national identity. It is this ideological edifice that the scientific evidence synthesized by Tony Joseph directly confronts and dismantles.

Contextualizing Early Indians

To fully appreciate the seismic impact of Early Indians, one must first understand the intellectual and political terrain it sought to reshape. The book did not emerge in a vacuum; it was a direct response to a century-long impasse defined by two deeply politicized and mutually exclusive narratives of origin, both of which, in their own way, have caused profound damage to an objective understanding of the Indian past.

The genesis of the Aryan Invasion Theory can be traced to the late 18th and 19th centuries, beginning not as a theory of conquest, but rather as a theory of linguistic kinship. Scholars like Sir William Jones, in his famous 1786 address to the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, discovered the profound structural similarities between Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and other European languages, leading to the classification of the Indo-European language family. This was a revolutionary linguistic insight. However, this discovery was soon co-opted and transformed by the racial theories sweeping across Europe. Figures like Friedrich Max Müller, while later recanting the purely racial interpretation in favor of a linguistic one, initially posited an “Aryan race” that migrated from a central homeland, with one branch moving into Europe and another into India (Müller, Biographies of Words and the Home of the Aryas).

In the hands of colonial administrators and ideologues, this linguistic theory was weaponized into a full-blown narrative of invasion and racial hierarchy. The AIT, as it came to be known, proposed that around 1500 BCE, nomadic, light-skinned, and culturally advanced “Aryans” from Central Asia swept into India with their horses and chariots. They were said to have violently conquered the indigenous, dark-skinned, and supposedly “primitive” Dravidian populations, pushing them southward and establishing a new social order—the caste system—with themselves at the apex. The Vedas, particularly the Rigveda with its hymns describing battles between the god Indra and the native Dasyus and the destruction of fortified settlements (pur), were interpreted as a literal, historical record of this conquest.

The political utility of this narrative for the British Raj was immense. First, it created a historical precedent for foreign rule, positioning the British not as alien conquerors but as the most recent in a long line of civilizing outsiders—fellow Indo-Europeans—who had brought order and progress to the subcontinent. It legitimized their presence by framing it within a historical pattern of beneficial foreign stewardship. Second, it served the classic colonial strategy of “divide and rule.” By positing a fundamental racial and historical schism between the “Aryan” north and the “Dravidian” south, and between upper-caste “Aryans” and lower-caste “aboriginals,” it fractured potential Pan-Indian unity and justified the existing caste hierarchy as a natural outcome of ancient conquest.

The Nationalist Counter-Narrative: The Out of India Theory (OIT)

As the Indian independence movement gained momentum and a national consciousness solidified, a powerful intellectual counter-current emerged to challenge the humiliating colonial narrative. This counter-narrative, which coalesced into the Out of India Theory (OIT), sought to reclaim India’s past from its colonial interpreters and establish an indigenous, autochthonous foundation for its civilization. In its modern form, it has become a cornerstone of Hindu nationalist (Hindutva) ideology.

The OIT argues for the exact reverse of the AIT. It posits that the “Aryans” and the Indo-European language family originated not in a foreign land but on the Indian subcontinent itself. From this Indian homeland, it is claimed, they spread their language, culture, and genes outwards to Iran, the Middle East, and Europe. Central to this theory is the re-identification of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), one of the world’s oldest urban cultures, as the “Saraswati-Sindhu Civilization”—a fully Vedic and Sanskrit-speaking society. Proponents, such as Shrikant Talageri in The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis, point to the Rigveda’s reverence for the Saraswati River (often identified with the modern-day Ghaggar-Hakra river system that dried up around 1900 BCE) as proof that the Vedas must have been composed in India during the height of the IVC, and not by later arrivals. The political imperatives driving the OIT are the mirror image of the AIT’s. By claiming that “Aryans,” Vedic culture, and Sanskrit are indigenous, the theory constructs an uninterrupted, pure, and glorious lineage for a specific vision of Hindu identity. This narrative establishes a claim to being the “original” people of India (bhumiputra or “sons of the soil”), thereby legitimizing cultural and political primacy and allowing for the marginalization of other religious communities as cultural outsiders.

(to be continued)

Cover Image: A photo of the Indus Valley Civilization’s large settlement, Mohenjo-Daro, in what is now Sindh province, Pakistan. The settlement was abandoned in the 19th century B.C. (Image credit: Pavel Gospodinov via Getty Images)