Let a ‘New Democracy’ Emerge from the Possibilities of Subaltern Politics

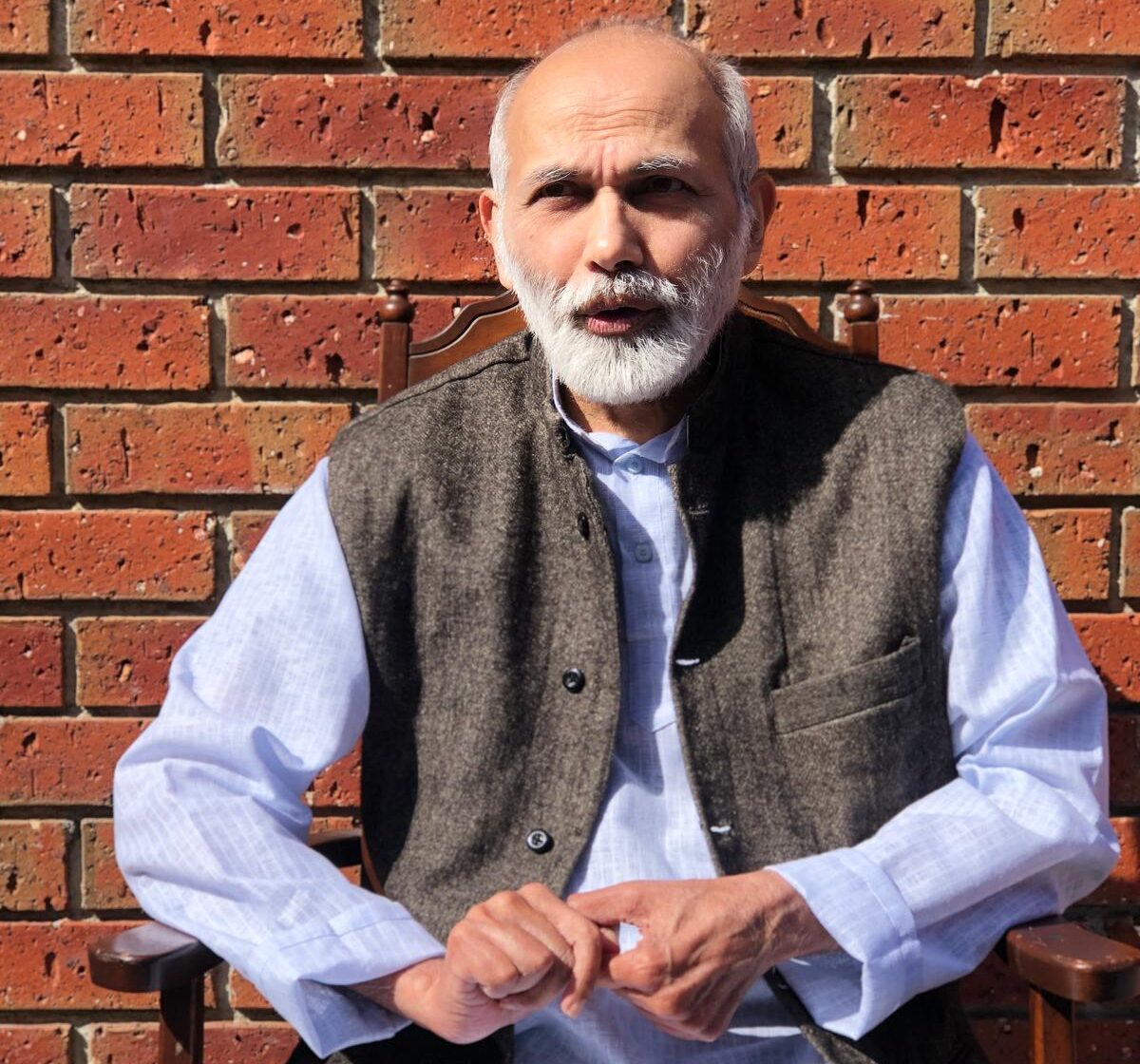

It is essential to examine the role of hegemony within democracy and how this form of power relates to capitalism. Subaltern identity represents humanity’s creative and persistent resistance to citizenship, as well as the expression of invaluable human experiences in opposition to the commodification of labor. A. K. Ravindran asserts the importance of subaltern politics in resolving the issues of liberal democracy.

A K Ravindran’s Notes on Social Justice, Democracy, and Subaltern Swaraj

Democracy is often believed to be self-government by the people, but this is a misconception. This misunderstanding persists because the difference between the two has not been meaningfully discussed in recent times. Today’s social climate does not allow for a fundamental questioning of democracy. Anyone who dares to question it risks being branded a fascist, a terrorist, or a sympathizer of anti-state movements. Perhaps that is why few are willing to take such a risk today. We live in an era where even communists are not expected to lead a revolution that moves beyond a mere return to democracy. Moreover, to critically engage with democracy at an ideological level, it is necessary first to ensure its civilized existence at a practical level.

Every democracy inherently divides people into two: the people and the anti-people. This reflects a fundamental characteristic of the democratic ideal: the tendency of any group that claims to represent the people to treat those outside it as enemies of the people. Its conception of the people renders them into a material good, and is unmindful of their agency. More laws, increased assertion of power — these are its hallmarks.

It is essential, therefore, to examine the role of hegemony within democracy and how this form of power relates to capitalism. Hegemony demands power, and regardless of which group holds governmental authority, it ultimately turns against the people. Even the concept of a subaltern democracy carries this limitation. This fundamental contradiction within democracy must be directly confronted.

Subaltern Identity

Subaltern identity represents humanity’s creative and persistent resistance to citizenship, and the expression of invaluable human experiences against the commodification of labor. Identity politics involves recognizing how individuals are subjected to various forms of oppression and exploitation based on their inherent identities — race, color, caste, and gender — and finding pathways to liberation. It is important to note, however, that the shortcomings of liberal identity politics should not be mistaken for the shortcomings of subaltern identity politics itself.

Liberal identity politics, at its core, is the identity politics of the upper class. It presents itself as the ‘common sense’ of the ‘public,’ yet it is unwilling to reveal its real identity. Proponents of this upper-class worldview believe they embody the ideal concept of humanity and see it as their duty to represent and reform the subaltern classes. Liberalism portrays any rupture in the self-image of the elite as a sign of societal disintegration.

Liberal identity politics assumes that subaltern classes are incapable of standing on their own or governing themselves. It thus adopts a paternalistic stance, claiming to protect and uplift them. Even class-based politicians, despite appearing critical of identity politics, often reproduce the same liberal mindset, framing subaltern uprisings as mere extensions of upper-caste religion and caste-based politics.

Religious identity should not be conflated with subaltern identities rooted in birth. Any expression of religious identity risks turning into hostility toward other religions if it is not grounded in the idea of a ‘multi-religious essence,’ as articulated by Narayana Guru. Religion attains completeness only when it emphasizes the essential unity of all faiths. Engaging with religious identities without upholding this spiritual unity risks falling into the same liberal trap.

Why the Subaltern?

The traditional understanding of the dominant class and the subaltern communities mirrors the old conceptual divide between heaven and hell. But why should the oppressed subaltern be consigned to hell? Is it not natural to aspire toward heaven? In the caste system, where upper and lower classes are rigidly determined by birth, should the lower classes not seek ascension, if not in this life, then in the next? Does this not require both willpower and effort?

In both religious and caste-based frameworks, the lower classes are depicted as sinful and wretched by karma and birth. Hence, escaping the lower classes and attaining an elevated status becomes the ultimate goal. However, self-respecting members of the lower classes can, through careful analysis, easily recognize whose interests these upper-class modeled narratives truly serve.

Subaltern self-government is fundamentally distinct from the democratic concept of governance. Subaltern is not simply the opposite of superiority or dominance. Like Nature itself, the subaltern communities embody fertility, creativity, and self-reliance. The upper classes, unable to survive without the labor and life of the lower classes, exist only by dominating them through the exercise of power. Thus, for the lower classes, self-government (Swaraj) is not only possible but profoundly liberating. Should we not then strive for micro-political self-rule by actively participating in democratic processes?

It is significant that while class politics often seeks to weaken, silence, and subjugate identity-based movements through violent steps, subaltern political movements do not mirror this aggression. In short, class politics and identity politics cannot be equated. While class politics is riddled with greater limitations, identity politics holds far more possibilities.