Hindutva and the Erasure of Indigenous and Dalit Histories in Education

The removal of Adivasi and Dalit histories from textbooks is a form of epistemic violence that erases marginalized knowledge to uphold caste hierarchies. This deliberate omission depoliticizes Dalit struggles and falsely portrays caste as a thing of the past, leaving privileged students unaware of ongoing systemic oppression in Indian society. Riyad Shajahan writes.

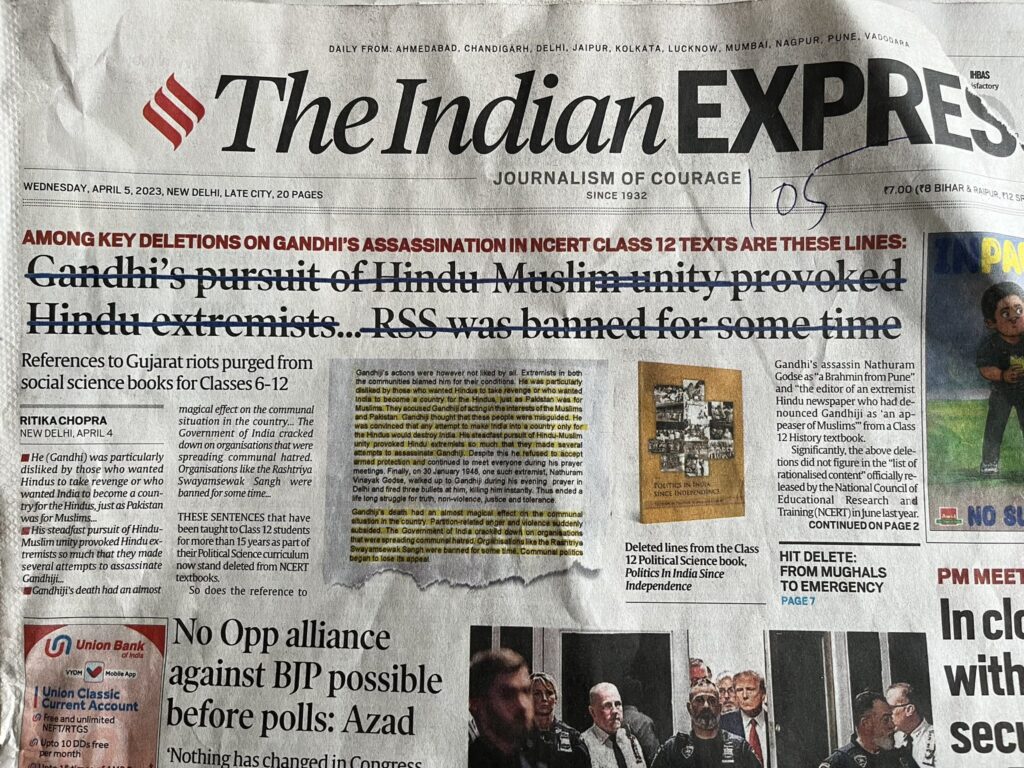

In contemporary India, the education system has become a battleground for ideological control, with Hindutva ideology rooted in the vision of a homogenous Hindu Rashtra, systematically reshaping narratives to align with its agenda. Recent reports reveal a troubling trend: the revision of school textbooks to erase references to significant historical events, such as the 2002 Gujarat anti-Muslim pogrom, and the omission of social movements led by Adivasis and Dalits. This deliberate erasure is not merely an editorial choice but a form of epistemic violence that undermines the histories, contributions, and identities of marginalized communities. By imposing a monolithic Hindu narrative, Hindutva-driven educational reforms reinforce casteist and colonial legacies, silencing subaltern voices and perpetuating systemic oppression.

Crafting a Monolithic Narrative

Hindutva, as articulated by ideologues like Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and M.S. Golwalkar, envisions India as a Hindu nation where cultural and historical narratives prioritize upper-caste Hindu identity. Since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) assumed power in 2014, this vision has infiltrated educational policy, particularly through revisions overseen by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT). Textbooks, which shape young minds and define national identity, have undergone significant changes to align with this ideology. References to the 2002 Gujarat pogrom, where over 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed in communal violence, have been removed from history texts. Similarly, narratives of Adivasi uprisings, such as the Santhal Rebellion of 1855, and Dalit movements, like those led by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, are either minimized or reframed to fit a sanitized, Hindu-centric version of history.

This pedagogical revisionism is not merely an act of historical omission but a strategic maneuver to consolidate Brahmanical hegemony. This serves a dual purpose. First, it absolves the state and Hindutva-affiliated groups of accountability for communal violence, such as the Gujarat pogrom, by erasing evidence of their complicity. Second, it marginalizes the histories of Adivasis and Dalits, whose struggles against caste oppression and colonial exploitation challenge the narrative of a unified Hindu past. By presenting history as a linear progression of Hindu glory, these reforms erase the pluralistic, multifaith, and multicultural realities of India’s past, which include significant contributions from Indigenous and Dalit communities. This erasure aligns with Hindutva’s broader goal of assimilating diverse identities into a singular Hindu framework, reinforcing Brahmanical dominance and sidelining subaltern voices.

The systematic erasure of Muslim freedom fighters like Variyankunnath Kunjahammad Haji from educational narratives exemplifies Hindutva’s assault on India’s pluralistic anti-colonial legacy. Haji, a revolutionary leader of the 1921 Malabar Rebellion, mobilized Mappila Muslims and Dalits against British colonial oppression and the feudal Jenmi system, establishing a proto-revolutionary governance structure in the Malabar region. Yet, Hindutva’s historiographical machinations, evidenced by the Indian Council of Historical Research’s proposed removal of Haji from the Dictionary of Martyrs, recast his rebellion as communal violence, echoing colonial propaganda that branded him a fanatic. This epistemicide not only distorts the revolutionary praxis of Muslim freedom fighters but also alienates contemporary Muslim youth, severing their connection to a heritage of resistance. Subaltern counter-praxis, through community-led archives and digital insurgencies on platforms like X, must reclaim these narratives, forging a decolonial historiography that centers the contributions of Muslims, Adivasis, and Dalits in India’s emancipatory struggle.

Epistemic Violence and Its Impact on Marginalized Communities

The removal of Adivasi and Dalit histories from textbooks constitutes epistemic violence, a deliberate act of suppressing knowledge systems to maintain power hierarchies. For Adivasis, whose oral traditions, ecological wisdom, and resistance movements like the Birsa Munda-led Ulgulan are integral to their identity, this erasure severs their connection to their heritage. For instance, the NCERT’s revised curricula often omit or downplay Adivasi contributions to India’s freedom struggle, portraying them as passive subjects rather than active agents of resistance. This not only devalues their historical agency but also perpetuates stereotypes of Adivasis as “backward” or “primitive,” reinforcing colonial-era biases that justify their marginalization.

Similarly, Dalit histories, particularly those tied to anti-caste movements, are systematically undermined. Dr. Ambedkar’s role in drafting the Indian Constitution and his advocacy for Dalit rights are often reduced to token mentions. At the same time, his radical critiques of caste and Hinduism are glossed over. Movements like the Dalit Panther Party, which challenged Brahmanical hegemony in the 1970s, are absent from mainstream textbooks. This selective amnesia serves to depoliticize Dalit struggles, presenting caste as a relic of the past rather than a living system of oppression. The result is a generation of students—particularly from privileged castes, who remain ignorant of the systemic inequalities that continue to shape Indian society.

The consequences of this epistemic violence are profound. For Adivasi and Dalit students, the absence of their histories in curricula fosters alienation and internalized inferiority, undermining their sense of self-worth and cultural pride. It also deprives them of role models who reflect their identities, limiting their aspirations in a society that already marginalizes them. For society at large, this erasure perpetuates casteist and colonial legacies, normalizing the exclusion of subaltern voices and hindering the development of a truly inclusive national identity.

Reinforcing Casteist and Colonial Legacies

Hindutva’s educational reforms do not exist in a vacuum; they build on and reinforce colonial and casteist frameworks. During British rule, colonial education systems prioritized upper-caste narratives while depicting Adivasis and Dalits as “uncivilized” or “untouchable,” justifying their exploitation. Hindutva’s revisions echo this approach by framing Adivasi and Dalit histories as peripheral to a glorified Hindu past. For example, the emphasis on Vedic texts and upper-caste figures like Chanakya overshadows the contributions of Adivasi leaders like Tantia Bhil or Dalit intellectuals like Jyotiba Phule, whose anti-caste activism laid the groundwork for social reform.

This alignment with colonial legacies is evident in the portrayal of Adivasis as obstacles to “development.” Textbooks often frame their resistance to land dispossession, such as protests against mining projects in Jharkhand, as anti-national, mirroring colonial narratives that criminalized Adivasi uprisings. Similarly, the omission of caste-based violence, like the 1996 Bathani Tola massacre of Dalits in Bihar, perpetuates a casteist silence that protects upper-caste privilege. By erasing these histories, Hindutva not only distorts the past but also normalizes present-day inequalities, allowing systemic oppression to persist unchallenged.

The erasure of Adivasi and Dalit histories in Indian education under Hindutva’s influence is a calculated act of epistemic violence that reinforces casteist and colonial legacies. By imposing a monolithic Hindu narrative, these reforms marginalize subaltern communities, alienate their youth, and perpetuate systemic oppression. However, through community-led documentation, alternative education platforms, digital activism, intercommunity solidarity, and policy advocacy, this could be challenged. Muslims, Adivasis, and Dalits can reclaim their knowledge systems and challenge Hindutva’s agenda. These efforts not only preserve their histories but also pave the way for a more inclusive, diverse, and humane society.

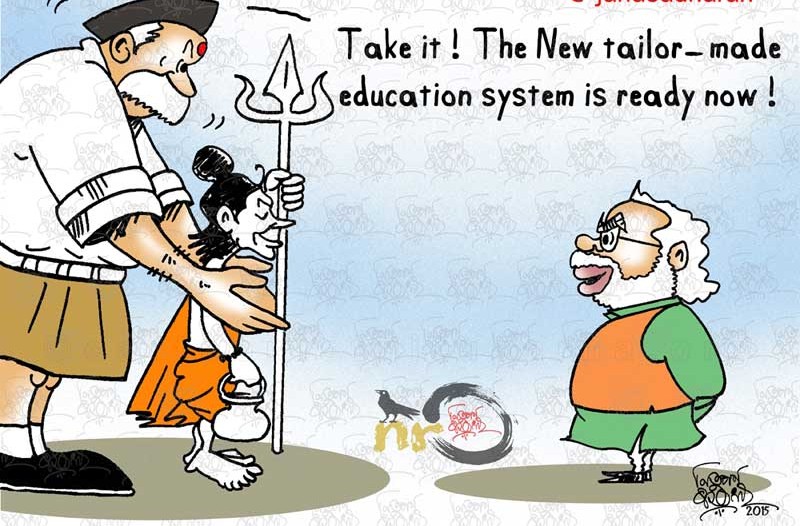

Cover image : Cartoon by Nituparna Rajbongshi