Colonial Knowledge and the Crisis of Acharam

The second part examines how colonial education and social reforms in late nineteenth-century Kerala challenged the Namboothiri order of acharam. As English-educated Nairs and others embraced new ideas of morality and family, traditional hierarchies were questioned. In response, Namboothiris formed the Yoga Kshema Sabha (1908) to defend acharam and their social dominance, even as a few within the community began cautiously adapting to modern education and changing times.

Part Two

8 Minutes Read

The New Challenges to the Order of Acharam

By the end of the nineteenth century, the British colonial government in India had established a wide network of educational institutions which included schools, colleges, universities and professional training institutions. The colonial practices related to these institutions produced a specific discourse of knowledge which intended to order native populations hierarchically according to their assumed relation with knowledge which can be called an order of colonial knowledge. The concept of the order of knowledge explains less about an ordered structure than about the process where objects, human beings and their actions were evaluated, indexed, transformed or excluded with reference to their relation to knowledge. The order of knowledge also denotes a condition of domination in which various social forces created hierarchical series by assigning indices to objects and actions with reference to knowledge. By the beginning of the twentieth century, this colonial discourse became dominant though it was not still hegemonic. The different caste communities in India responded in different ways—such as negotiation, adaptation, resistance, distancing or neglecting—to the colonial domination and this transformed their existing practices of knowing.

The last decades of nineteenth century witnessed dramatic changes in the caste practices of jatis, like Nair, Ezhava, and Pulaya in the Malayalam-speaking region Kerala, which comprised the princely states of Thiruvithamkoor and Kochi and the British-ruled district of Malabar. In Malabar, it was Nairs who began challenging the order of acharam based on their newly acquired status within the colonial administrative apparatuses. By the end of the nineteenth century, a number of individuals from Nair caste, who were trained in various colonial educational institutions, attained positions of power such as revenue administrators, magistrates village officers and police officers. Their participation in the colonial practices produced new ideas of individuality and new concept of norms and values regarding social life.These ideas, which were predominantly influenced by colonial discourses, were not commensurable with the existing order of acharam imposed by Namboothiris. The interaction of Nairs with colonial discourses produced new notions of family and morality and Nairs, under the leadership of educated individuals, started revaluating and questioning the existing norms and values, especially regarding the special conjugal practices Nair women had with Namboothiri men.

In the period of interest, in a Namboothiri household only the elder son married from within the caste. The younger brothers practiced a particular kind of conjugal relation—which was known as sambandham—with women from the upper castes, including Nairs. Children born in these relations did not belong to the Namboothiri caste but to that of their mothers. The women or children in the sambandham relation did not have any right to the property of their ‘husband’ or father. Nairs followed a matrilineal system and property was transferred through the lineage of women. Many among the Nair women practised serial monogamous relations with upper-caste men including Namboothiris. Theoretically, a Nair woman could suspend one such relation and begin a new one on her own. Typically, however, the suspension of a conjugal relation was more complicated. But the idea of chastity was not a factor in this system.

The colonisers and missionaries considered this matrilineal system unhealthy, uncivilised and immoral. English-educated Nair men in the late nineteenth century attempted to reform this lineage system through various channels including legal enactment. They demanded that Nair women should ‘properly’ marry from within the caste and follow patrilineal monogamous conjugal relations. They influenced the British administration successfully to pass an act in the Madras legislative assembly, which was named as the Malabar Marriage Act of 1896. The act envisaged to make sambandham a legal marriage so that the wife and children in the marriage would have the right to the property of the husband. Namboothiris considered this as a challenge and threat to their economic power and to acharam. Nampoothiri community leaders started propaganda against this Act through articles and memorandums in the first decade of the twentieth century.

The second challenge to the order of acharam originated from the British government’s attempts to reform the land revenue system in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. From its inception in Malabar in the late eighteenth century, British rule granted full ownership of the land to janmis (landlords). Their objective was to create manageable and defined land authorities from which they can collect tax, which was the major portion of their revenue. This destroyed the age-old arrangement between the janmis and the kutiyans (tenants). Now the janmis were able to evict a tenant more easily and to pressurise kutiyans to pay ever increasing rents. The tenants, especially the Muslim tenants protested against this in different ways from the beginning of the nineteenth century. Low-level officers of the British government warned that this might lead to serious riots and rebellion. Once the situation became alarming, in 1880, the government appointed a special commission headed by William Logan. Logan in his report suggested important reforms including the prohibition of large-scale evictions of the tenants by the janmis. Government did not enact any legislation based on Logan report, but from this period onward we witness a number of inquiry commissions, legal discussions and heated debate among the janmis and kutiyans which by the end of the century culminated in formation of separate organisations both by janmis and kutiyans.

The debate around the above mentioned bills in the Madras assembly and the propaganda for and against the bills outside created anxiety and tension among the Namboothiri janmis. They reasoned that English education, and the reforms that accompanied it, were the root of the problem. A few Nampoothiris who were closely following the debate of various reforms in the first decade of the twentieth century occasionally wrote articles in contemporary Malayalam journals and newspapers. In an article in 1903, Narayanan Namboothiri reminded the Nairs and the British government that ‘there are certain things that are more valuable than knowledge and parishkaram (reform) for a society’. He claimed that it was acharam that existed from time immemorial that protected the culture of the country. According to him knowledge of the universe was a result of ‘good practices’ in daily life, not the cause or basis for a good life. P.K. Nampoothiri, a strong proponent against the bills, argued that the reform bills in the legislative assembly reflected the ‘new ideas of the educated class and their total disrespect to the age old customs’. He warned that the bills, if enacted, would create ‘social disorder and chaos’ among the upper castes.

Even though the Madras government did not enact any bills which would have curtailed the rights of janmis, it was clear from the overall debate that the educated Nairs were closer to the government and more influential than Namboothiris. It is important to note here that the Nair reform process was not just a reaction and acceptance of the colonial discourse. In the Nair reform discourse there was not only the questioning of existing acharam but also the re-imagining of acharam and attempts to invent new acharams which will be appropriate in the new order of knowledge. There were similar moments in the reform movements in other communities such as Syrian Christians and Ezhavas as well; in each case there was a claim of golden past and a demand for the revival of certain acharams in new forms according to the needs of the new order of knowledge.

The situation gave a clear message to Namboothiris that occasional articles in journals or a few meetings of interested parties were not enough to overcome the challenges they were facing at the period. It was in this context that Namboothiris formed a community organisation, the Yoga Kshema Sabha (YKS) in 1908. At its formative period the major objective of the organisation was the protection of the order of acharam and the maintenance of dominance in the emerging new order of knowledge.

The YKS and the Protection of Acharam

In its initial years, conservative janmis in the community controlled the YKS. In this period the objective of the YKS was not widen the base or to mobilise each community members. Rather, the Sabha was a body of a few elites who imagined their interests as the interest of the community. The resolution passed in the first meeting of the YKS stated that ‘no member of the Sabha should utilize the platform of the same to speak, decide or act against acharam and customary traditions of Nampoothiris’. M.R. Bhattathirippad remembered that until the seventh annual conference in 1915, Sabha did not take any positive action regarding English education, women’s education, sambandham, or dress reform.

Several of the Namboothiri authors echoed Nagam Ayya’s opinion, mentioned earlier, and defined acharam as a force that extended beyond the Namboothiri world. For example, Krishnan Nampoothiri claimed that different jatis have different kinds of responsibilities towards society. The responsibility of the Namboothiri jati was ‘the performance of rituals and the maintenance of acharam that are necessary to keep the whole human world happy and peaceful’. Even a single person’s activity that violates the code of acharam could invite a number of sins and create different kinds of difficulties in daily life. According to the author, Namboothiris responsibly performed the rituals in proper ways without hesitating to expel even powerful persons from the community who deviated from the rules of acharam. ‘The superiority of the Nampoothiri Jati was commonly approved for the above reason’. In short, in the first decades of the twentieth century, in the context of their attempt to protect the order of acharam, Namboothiris began claiming that acharam was a matter of all castes and it was Namboothiris duty to protect acharam for the well-being of all castes.

In its initial years, the leaders of YKS argued that colonial education and reforms accompanying it were totally antithetical to the rules of acharam. The first and foremost point of their objection was regarding the rule of untouchability. The conservative leaders defined acharam based on the notions of purity and pollution. According to this concept each object, human beings and actions were either pure or polluted. Namboothiris could not touch anyone outside the caste without being polluted. The degree of impurity depended on the caste of the individual: the lower the position of the caste, the higher was the impurity. Hence it was impossible for Namboothiris to attend a school without violating the rules of acharam, where all the objects (like pen, paper, etc.) and other human beings (other lower-caste people) were polluted. The conservative section of Namboothiris argued at this period that threat of being polluted was one of their reasons for not participating in colonial educational institutions.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, a new group of individuals from within the community began questioning the conservative leaders of the community. These individual did not challenge the order of acharam as such. Their attempt was to incorporate education within the order of acharam. They argued that Namboothiris could and should redesign the daily life of a Namboothiri boy so that he could attend school and keep himself pure. V. Keshavan Bhattathirippad suggested that ‘not eating at school and taking a bathe after school before entering into illam’ were sufficient to keep a Namboothiri boy unpolluted. At this period this was a minority voice which did not have much influence among community members.

(to be continued)

Courtesy: SAGE Publications

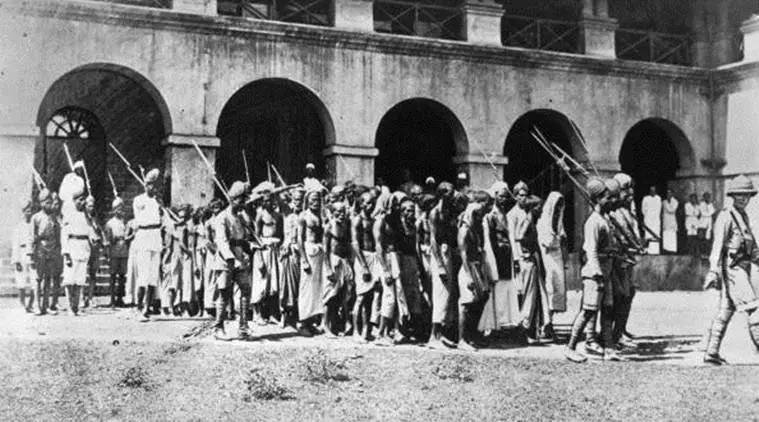

Cover Image: The Malabar rebellion was an armed revolt staged by the Mappila Muslims of Kerala against the British authorities and their Hindu allies in 1921. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)