Climate change will collapse the healthcare delivery system in India

Climate change is no longer a distant threat but a lived reality in India, with disasters like the 2024 Wayanad landslide exposing both the human cost of environmental degradation and the failures of governance. Drawing on scientific evidence and lived experiences, this article by Sagar Dhara argues that unchecked warming, deepening inequality, and collapsing ecological systems will overwhelm India’s healthcare delivery system. Only a radical, justice-centered global response led by vulnerable communities can avert this looming health catastrophe.

Salim’s death in the Wayanad Disaster was not an Act of God

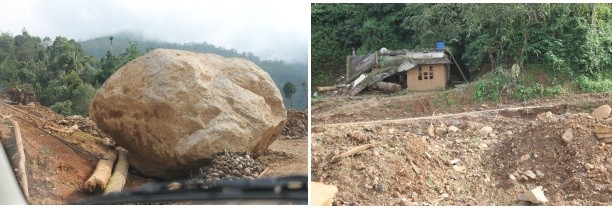

On 29 July of last year, Salim, who stays in Mundakkai, the epicentre of the 2024 Mundakkai Landslide Disaster, heard of the Hume Centre for Ecology and Wildlife Biology warning on the high probability of landslides in Meppadi Taluka of Wayanad District. He had just built a new house, but abandoned it as it was directly in the pathway of a possible landslide. He relocated with his family to Pady, which he felt was a safer place. Soon after moving to Pady, he started helping others evacuate their homes. When the landslide struck in the wee hours of 30 July, Salim was hit by a boulder and died.

Per the government, the Mundakkai Landslide Disaster killed 254 people. The local people, though, believe that the death toll may be closer to 1,000.

In an interview the author did with the Wayanad District officials on 16 May 2025, they said the landslide was an Act of God, implying that the event could not have been foreseen and that little could be done to avoid loss of life. This belief does not hold. The 2024 Wayanad disaster is a consequence of human interference with nature at the global and local levels. Both could have been avoided or their impacts foreseen, and action taken to avoid the disaster.

Since the Industrial Revolution began some 300 years ago, the Global North has been responsible for 70% of carbon emissions that have been pumped into the atmosphere. A warming of 1.3 °C that has occurred is an interference with nature at the global level. For decades now, scientists have warned that global warming will increase the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events of the sort that occurred in Mundakkai on 30 July 2024 and in Idduki in August 2018.

Over the last century, plantations have replaced forests in many parts of the Western Ghats, including in Idukki and Wayanad. Plantations do not grip the soil as well as forest species. Consequently, heavy rains wash out surface soil, loosen embedded rocks and boulders, and cause landslides. This is interference with nature at the local level.

Avoiding a disaster requires predicting it, sounding a warning and heeding it, and evacuating people from harm’s way before a landslide occurs. Based on rainfall data from 200 meteorological stations they set up in Wayanad District, the Hume Centre warned the District Administration of the high probability of a landslide event well before the landslides occurred. Unfortunately, the warnings were not heeded.

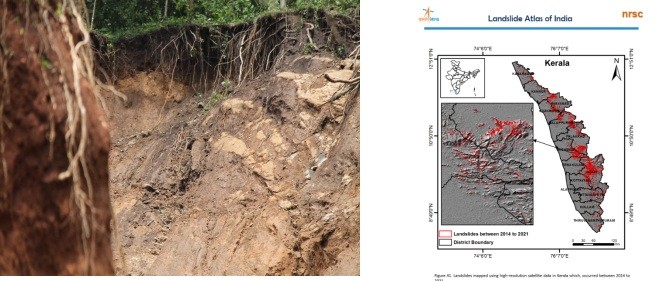

The Landslide Atlas of India, published by the National Remote Sensing Centre, Hyderabad, indicates that Wayanad District is a landslide-prone district. Several other studies indicate the same.

The availability of all this information suggests that the Mundakkai Disaster could have been avoided if the government had acted with foresight and installed systems to predict and warn of landslides, as well as prepared village-level landslide response plans in landslide-prone areas of Wayanad, and heeded the Hume Centre’s warning. Labelling the Wayanad Disaster as an Act of God by the Wayanad District authorities is trying to pass the buck after dereliction of duty.

Climate change action is failing

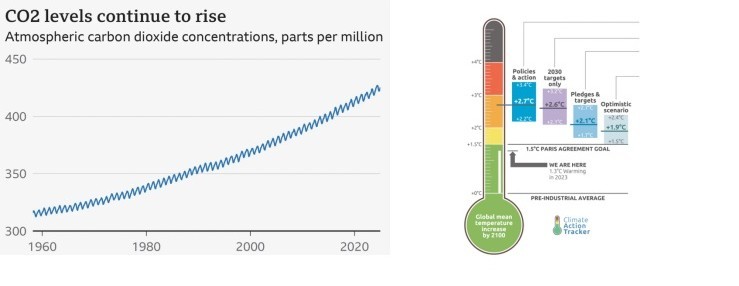

Global warming is a consequence of fossil fuel overuse and deforestation. These two processes have emitted about 2,500 Gt of CO2e to date, increasing the atmospheric CO2 concentration, which was stable at 280–300 ppm for 800,000 years before the industrial revolution, to 423 ppm today. Carbon emissions are global pollutants as they spread throughout the atmosphere, no matter where they are released. To undo the warming, carbon emissions must become net zero.

In 2015, the nations of the world signed the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5–2°C above pre-industrial times, above which catastrophic consequences may ensue. To restrict warming to less than 1.5oC only an additional 100-400 GtCO2 may be emitted. At the current emission rate of 40 GtCO2, the remaining carbon space will be erased in the next few years. To avoid warming above 1.5°C, GHG emissions must be halved by 2030 and become net zero by 2050.

Under the Paris Agreement, each nation made non-binding pledges to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and sequester additional atmospheric CO2. These pledges will fail as GHG emissions are rising by 1.3% pa instead of dropping by 8-9% pa, which is necessary to meet the 1.5°C warming ceiling. If all the Paris Agreement pledges are implemented, given the current emissions trajectory, warming by the year 2100 will exceed 2 °C, and if the pledges remain unfulfilled, warming will be closer to 3°C. At these warming levels, the future is bleak.

The Wayanad Disaster is not a one-of-a-kind climate-related health impact in India

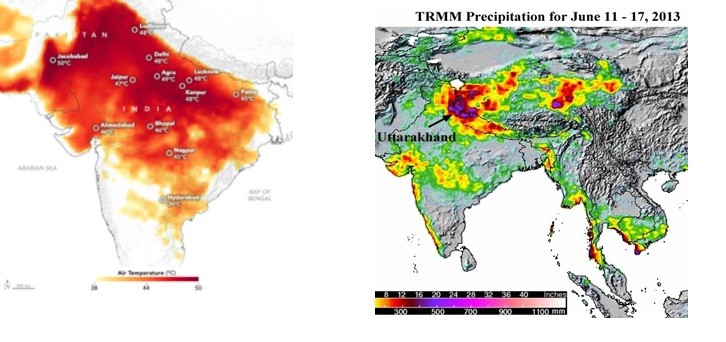

Climate change poses a clear and present danger to human health as warming causes heat stress, floods and landslides, the spread of vector-borne diseases, and alters precipitation patterns that compromise food and water security.

Climate change-related health impacts have become visible in the last two decades. However, estimating them poses challenges. A summary of available estimates of climate change-related health impacts is presented below. These figures should be taken as indicative and not definitive.

- Heat stress: ~24,000 deaths (1992-2015),

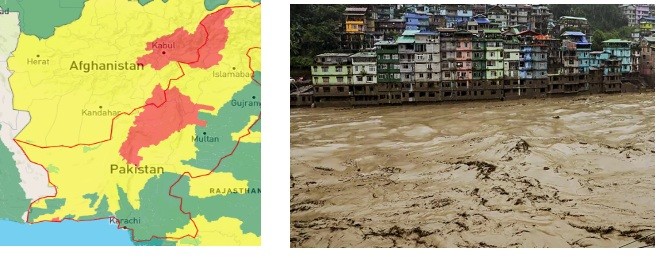

- Floods and landslides: ~15,000 deaths (2000-2020) , 12% of India is flood-prone, affecting 40 million people annually

- Heat-related chronic kidney disease: ~20,000/year,

- Dengue: Increased from 4,000 cases/year in 2000 to 1,88,000 cases/year in 2020,

- Malaria: Climate change has expanded mosquito habitats, contributing to ~1.5 million cases annually,

- Malnutrition: Climate change-related crop losses (wheat and rice) have increased malnutrition, causing an estimated additional 14,000 child deaths/year.

One study on the heat stress and mortality done in Surat concluded that “There is an increase of 11% in all-cause mortality when the temperature crossed 40oC. There is a direct relationship between mortality and HI (high heat index). Mean daily mortality shows a significant association with daily maximum temperature and the HI.”

Another recent study established a correlation between high temperatures and chronic kidney disease (CKD) in rural areas by reviewing studies done in several continents—Asia, North and South America and Africa. The study found confirmed sites in India, Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala where CKD correlated with heat stress, and found other sites in India, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Mexico and United States where CKD incidence is suspected to be associated with heat stress. The study concluded that:

“One of the consequences of climate-related extreme heat exposure is dehydration and volume loss, leading to acute mortality from exacerbations of pre-existing chronic disease, as well as from outright heat exhaustion and heat stroke. Recent studies have also shown that recurrent heat exposure with physical exertion and inadequate hydration can lead to CKD that is distinct from that caused by diabetes, hypertension, or GN. Epidemics of CKD consistent with heat stress nephropathy are now occurring across the world.”

The list of major floods, landslides, cyclones and heatwave events in the last two decades, indicates that global warming has begun to take a heavy toll on human life in India.

South Asia—A climate change hotspot

South Asia has a quarter of the world’s population, but has emitted only 3.6% of the world’s historic cumulative emissions. Yet, it is one of two regions that will be most affected by climate change, the other being the Sahel region in Africa.

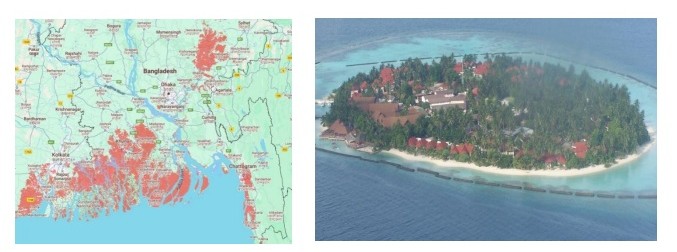

With a likely 3 °C warming by 2100, sea rise will submerge approximately 20% of Bangladesh’s land mass, which will create an estimated 100 million climate refugees, and completely drown the island nation of the Maldives, causing its entire population (current population ~5 lakhs) to take refuge in other countries.

Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka will be severely water-stressed within the next few decades. The Indus and Amu Darya, which flow through Pakistan and Afghanistan, are dependent to the extent of 60-75% on snow and glacial melt, whereas the Ganga and Brahmaputra get only 10-20% from meltwater.

As glaciers melt with warming, the water volume in glacial lakes will increase. If the moraine dam that holds the glacial lakes gives way due to increased pressure, a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) will carry millions of tonnes of water up to 100 km downstream, washing away villages and farms and everything on them. The entire Himalayan region is at risk of GLOFs, as happened on 4 October 2023 in Sikkim, probably due to a landslide into South Lhonak Lake.

Estimated future climate-related health impacts in India

Literature that estimates projected morbidity and mortality due to climate change is sparse. Yet, estimates from available literature are presented below. These figures should be interpreted as being indicative of the possible magnitude of the problem and not as being accurate estimates. Climate change-related health impacts in India estimated for the near future are:

- Heat stress:

- Mortality–By 2050, 30,000-50,000 deaths annually,

- Morbidity–Increased cases of heat strokes, cardiovascular stress, and dehydration, especially among labourers, the elderly, and the urban poor. Productivity losses could cost ₹ 13-22 lakh crores annually.

- Floods and landslides:

- Mortality— ~10,000 deaths/decade,

- Morbidity—Increased risk of drowning, injuries, and infectious diseases (cholera, leptospirosis). Displacement could affect 50–100 million people by 2050.

- Heat-related chronic kidney disease:

- Morbidity–Rising temperatures and dehydration among agricultural workers may increase CKD cases by 20–30% in drought-prone regions, particularly Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu

- Malaria, Dengue, Chikungunya:

- Morbidity–Expansion into new regions due to warmer, wetter climates could lead to 100,000+ additional cases annually. WHO projects 10-15% expansion of malaria/dengue zones in India by 2050. Warming in the Himalayan foothills will lead to the resurgence of malaria.

- Water stress and drought: Chronic water scarcity may lead to 50–60% of India’s population facing severe water stress, increasing risks of diarrheal diseases, kidney disorders, and malnutrition. 40% of Indians will lack adequate drinking water by 2030, and 21 cities will exhaust groundwater by 2050.

- Sea rise: 1.5–2.0 mm/year sea-level rise, threatening 28 million coastal residents by 2050. Some estimate that up to 50 million people may be affected by sea rise.

- Morbidity–Salinisation of freshwater leads to hypertension, kidney disease, and loss of livelihoods.

- Glacial Lake Outburst Floods: 5 million people in India are at risk due to GLOFs.

- Food insecurity: Heat stress and erratic monsoons may drop rice and wheat yields 10–30% by 2050, and reduced pulse production may lead to protein-deficient diets. Agricultural losses may mount to ₹ 2.6-4.5 lakh crores annually, pushing 50 million more Indians into hunger. Climate migrants, e.g., farmers abandoning fields, will face higher food insecurity.

- Nutritional deficiency:

- Morbidity–Iron, Zinc, and Vitamin A deficiencies may worsen due to declining crop nutritional quality. 50 million+ women and children at risk of anaemia due to reduced iron bioavailability in staple crops.

- Malnutrition:

- Mortality–An additional 1.5-3 million child deaths (cumulative till 2050) may occur due to climate-aggravated undernutrition. 50,000-100,000 annual deaths from malnutrition-linked conditions (diarrhoea, pneumonia, measles) exacerbated by climate shocks

- Morbidity--10–15% increase in stunting (low height-for-age) due to reduced dietary diversity and food insecurity. Wasting (acute malnutrition) could rise by 5–10% in drought-prone regions of India.

- Cascading Effects (Disease, Poverty, Displacement)

- Morbidity–Diarrheal diseases (from water contamination) may reduce nutrient absorption, worsening child malnutrition.

These figures look like dry numbers in a research paper. But behind every one of them, there will be a tragic story of a “Salim” that will haunt the near and dear of the affected persons. As with other health risks, the poor and the vulnerable, the aged and the young, particularly in the Global South, will be the hardest hit by climate change-related impacts.

Climate health solutions are beyond state health policy measures and individual lifestyle choices

Health risks—infectious and communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases, nutritional deficiencies, injuries and trauma, mental health and genetic disorders, environmental and occupational health risks—are managed with two devices: state health policy and programmes, and an individual’s lifestyle choices.

State policy and programmes include public health programmes (universal healthcare, vaccinations, preventive screenings), infectious disease control (sanitation, pandemic preparedness), mental health management (counselling services, reducing stigma) and social support (reducing health disparities).

Individual lifestyle choices include regular physical activity, adequate sleep, stress management, and avoiding consumption of harmful substances (tobacco, drugs, excessive alcohol). The rich have additional choices as they can afford high-quality healthcare, a balanced diet (nutritious food, reduced processed foods), and a healthy environment (clean air and water, green neighbourhoods, and good sanitation).

These devices, i.e., state health policy and programmes and individual lifestyle choices, are ineffective in managing climate health. While emissions happen at the national level, their cumulation in the atmosphere makes climate change a global process, and therefore, their removal requires a coordinated international response, which is lacking. Individual nations, even the largest carbon emitters such as China and the richest nations such as the USA, cannot alter the trajectory of climate change on their own. For example, India cannot on its own stop or mitigate sea rise, the increase in extreme weather events, or temperature rise and rainfall changes, through state policy interventions through policy changes. International cooperation alone can mitigate climate change.

Likewise, individual lifestyle choices such as adequate sleep or good nutrition will not thwart the occurrence of floods and landslides or GLOFs. The rich can make a few lifestyle choices that may put them out of harm’s way for some warming processes, e.g., buy space cooling devices for their homes or relocate homes from landslide pathways. But even the rich cannot completely avoid all the climate change-related health impacts, e.g., extreme weather events such as very heavy rainfall events and consequent floods.

Divided stakeholder countries fail climate solutions

The intergovernmental body, Conference of the Parties (COP), tackling climate change, is a divided house, and has feet of lead while making decisions. Three groups of nations gather annually for the COP meetings, each pulling in a direction that is tangential to the other two. Discussion in the COPs even on minor issues is agonisingly prolonged, and consensus on key issues is often out of reach.

The first group, the Global North, with 16% of the global population today, has consumed 70% of all fossil fuels used since the Industrial Revolution. Whereas the Global South, with 84% of the world’s current population, has used only 30% of the fossil fuels. The Global North has achieved a relatively high material living standard. The average per capita GDP of high-income countries in 2018 was US$44,787, i.e., 10-fold greater than that of low- and middle-income countries (US$4,971), and 20 times that of South Asia (US$1,903). The Global North does not want global warming to lower its living standards and prefers to use its enormous financial resources to use technological solutions to control carbon emissions.

The second group of nations are the “wannabe Global North” nations that are part of the Global South but believe that they have material and human resources, if not the financial means, to soon become part of the Global North, e.g., India, China, Indonesia, South Africa, and Brazil. The slogan “Vikasit Bharat by 2047” (a developed India by 2047) coined in India is based on this belief. Many of these countries have large fossil fuel deposits that can power their development, e.g., India, China, Indonesia and South Africa have vast coal reserves that they can exploit cheaply. Thermal power plants contribute the bulk of the power generated in India (77%) and China (65%). Their reluctance to sign a pledge to phase down unabated coal use in recent COP meetings stems from their energy choices. They justify their continued carbon emissions by arguing that if the Global North used fossil fuels to power their development, then climate justice demands that the Global South can do the same.

The third group of countries is the Global South that does not have the material and human resources, e.g., Nepal, Bangladesh, most of the African countries and the small island nations. They therefore do not aspire to become a part of the Global North. They demand that the Global North and the “wannabe Global North” reduce their emissions drastically so that the Global South is not badly impacted by climate change.

Frustrated with the intergovernmental negotiations, the Climate Vulnerable Forum, a group of 74 highly climate vulnerable nations, requested COP 26 Presidency to incorporate a “Climate Emergency” in the Glasgow Pact that encompasses a delivery plan for the annual $100 billion climate finance from the Global North and mandate yearly target raising at each COP, especially by high carbon emitting countries.

Climate Vulnerable Forum members

While the forum’s intentions are laudable, its suggestions are within the ambit of a failed demand-side management that the COPs seek. The window for restricting warming to below 1.5 °C, using current measures, has almost closed. The Global South is caught in a Catch-22 situation. If they burn more fossil fuels to “develop,” they will contribute to warming that will exceed 1.5–2°C. The Global South is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts, and further warming will hurt them the most. If the Global South restricts its emissions, it will remain permanently materially backward in comparison to the Global North. And even if the remaining carbon space of 400 GtCO2 is given to the Global South, it cannot achieve the material standards of the Global North.

What ails climate solutions?

The world is disunited in finding solutions for climate change for several reasons:

- Global North and South have divergent objectives: The Global North, the “wannabe Global North,” and the Global South are not on the same climate action page. They are at different stages of material development and have divergent objectives, which are in part opposed to one another. It is therefore difficult for them to act in unison, a prime requirement for a successful climate change solution (see above subsection).

- Global South lacks resources: The Global South lacks the financial resources and technical know-how to make the energy transition to phase out carbon emissions. The Grantham Institute estimates that emerging markets and developing countries, excluding China, require an additional US$1 trillion per annum by 2025 beyond domestic funds that they can muster for climate change mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage, and $2.4 trillion per annum from 2030. The availability of finance is far short of the estimated requirement. In the 2009 Copenhagen COP15, the Global North committed to mobilising $100 billion per annum as the Green Climate Fund by 2020. This commitment was fulfilled only in 2022.

Climate finance provided and mobilised in 2013-2022 (US$ billion)

In the 2024 COP 29, a global climate finance target, the New Collective Quantified Goal for Climate Finance, was established to collect at least $300 billion annually by 2035, with the Global North leading the mobilisation efforts. This goal aims to support the Global South in their climate adaptation and decarbonization initiatives. However, many developing countries criticised the amount as insufficient, arguing that it falls short of the $1.3 trillion per year they deem necessary.

- Varied vulnerability to climate change: The Global North is less vulnerable to climate change impacts than the Global South. With warming, lands in the temperate regions and close to the Arctic and Antarctic circles are expected to become more productive. It is also believed that there are significant oil reserves under the Arctic Ocean. The Global North, which occupies these lands, is therefore less motivated to combat global warming than the Global South.

- War over liability for climate change-related loss and damage: The Global North grudgingly accepts that it has emitted a majority of the cumulative carbon emissions, as there is overwhelming evidence for this. However, it shies away from accepting responsibility for its emissions as it implies accepting legal liability for the climate change-related loss and damage in the Global South. Since there is no agreement on what constitutes climate justice, the Global North and South are at war over liabilities and reparations.

Climate change—A consequence of growth and inequity

Climate change is one of three tipping points that human society faces today, a consequence of growth and the inequitable distribution of surplus generated from growth.

Among all species, only humans can create knowledge of energy conversion (science) and have used it to extract resources from nature to make artefacts (technology). To obtain energy from nature, e.g., wind, fossil fuels, crops, etc, humans have to make an energy investment. The energy return from the energy source is greater than the energy investment made to obtain it. The difference between the harvested and invested energy is surplus energy, which allows for diverting a part of human labour from producing energy to producing artefacts and services (division of labour). If surplus energy is reinvested in harvesting energy, net surplus energy increases, allowing for population growth and a greater amount of artefacts and services to be produced, i.e., economic growth.

The Earth is finite and has limited natural resources and a limited capacity for neutralising waste byproducts from artefact production. Local environmental degradation, e.g., polluted air and water, is an indication that the local environment’s capacity to neutralise wastes has been reached. The buildup of carbon emissions to levels 50% more than pre-industrial times, and the consequent warming that now poses a serious risk to human society, indicates that the limits of the global environment to absorb carbon emissions have almost been reached.

Climate change is one of three inflexion points that we face today. Any one of them can independently cause society to regress or even tip over if their red lines are crossed.

The second inflexion point is the overuse of nature and, consequently, the drastic depletion of natural resources, particularly non-renewable minerals. This phenomenon is represented by the term “Peak oil”, which is that oil production is expected to peak around 2030 and then decline. This process will happen with other non-renewable minerals as well.

Humans have used about 40% of the known fossil fuel reserves. Oil and gas will be exhausted in about 50 years, and coal in 100 years. None of the alternate energy sources—solar, wind, nuclear—can replace fossil fuels completely. Eighty critical non-renewable mineral ores, including iron ore, bauxite, and copper ore, will be in short supply in 50-70 years. Energy and material exhaustion have in the past led to civilizational collapses. Human society today faces a global civilizational regress or collapse, the health impacts of which may be more severe, in terms of mass hunger and deprivation, than those of climate change.

The third inflexion point is the growing global inequality. The income of the top 1% of the world’s population is 19%, while that of the bottom 50% is 9%. Income disparities are growing all over the world, except in Europe. In India, the top 10% of the population commands an income of 65%, while the bottom 50% gets only 12%, and the disparity is growing.

Growing inequality will trigger conflict between and within nations, hunger and disease. Three types of wars—Interstate, colonial and civil wars—killed more than 140 million people in the last century. With trickle-down theory having failed, it will take more than 100 years to pull 800 million people out of poverty.

Ideologies that support growth

Two ideologies—anthropocentrism and ownership of wealth provide the impetus for growth by legitimising resource theft from nature and its unequal distribution among humans.

Anthropocentrism prioritises human consumption of nature in the belief that humans are the most important species and that the rest of nature is for their use. Anthropocentrism legitimises the unbridled theft of energy and materials from nature at the expense of all other species. Anthropocentrism is epitomised in v 1:26, Book of Genesis, And God said, let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

While other religions may not be so overt in their pronouncement of human superiority, their followers have been just as anthropocentric in practice.

Ownership rights over wealth came into existence 5,000 years ago when slavery began. Ownership rights have persisted through slavery, feudalism, capitalism, and post-capitalist societies. In the first three modes of production, individuals and the state had ownership rights. In capitalism, organisations could also own wealth. In post-capitalist societies, ownership rights were largely vested with the state. Some post-capitalist countries allowed individual and private enterprises to own wealth.

Ownership of wealth creates the impetus for the owner to maximise the accumulation of surplus energy and wealth. For example, by investing 1 J in coal production, a surplus energy of 19 J is obtained. It now makes sense to invest 2 J out of the surplus to get a return of 38 J of surplus energy. This process becomes a virtuous cycle of energy investment to harvest energy à Surplus energy à More investment to harvest more energy à More surplus energy à ……, and so on.

The owner of wealth thus accumulates a greater amount of wealth, whereas the non-owner (worker) does not accumulate wealth. Ownership of wealth is the basis for inequality and its growth.

The energy investment to obtain energy is for prospecting, extracting, transporting and sometimes doing some processing of the obtained energy, e.g., refining crude oil, to make it user-ready. Yet the investor, whether a private party or the state, makes an ownership claim over the entire energy source despite the energy source being created by nature and not humans, e.g., nature made fossil fuels by baking dead vegetation and animals under pressure and temperature in Earth’s bowels. The concept of ownership is a human construct and not rooted in physical laws.

The expansion of surplus energy leads to the extraction of greater quantities of raw materials from nature to convert them into goods and services. Ownership of wealth has contributed to the overexploitation of resources from nature.

Climate change will collapse the health care delivery system in India

Climate change is a global problem and requires a unified global approach to radically reduce carbon emissions, yet that ensures climate justice. This has not happened as the COP is a divided house. And there is a lack of consensus on what constitutes climate justice. A warming of ~3 °C by the end of the century will have a serious impact on public health, particularly in the Global South.

If the world fails to find solutions for Peak oil and rising global inequality, the health impacts of these two inflexion points will add to those of climate change in a domino effect and create a global health crisis of catastrophic proportions.

As long as warming persists, an individual nation’s health policies and programmes, no matter how good they are, will have a marginal effect in mitigating climate change health impacts. Likewise, lifestyle choices for better health will not be of much help in tackling climate change impacts.

In short, the current health care delivery system will fail to tackle climate health issues and collapse.

A rainbow coalition of the world’s vulnerable people with a radical mission is the last resort.

The only way to avoid climate change’s burden of disease and death is by keeping warming below 1.5 °C and reducing it further as quickly as possible. The COP is likely to fail in doing this. The only other body of last resort that can do this is the climate-vulnerable people of the world. They have the very daunting task of forming a global rainbow coalition and creating a radical programme that contains warming to less than 1.5 °C. Such a programme must tackle climate change by making society a truly sustainable and equitable one. A draft mission statement for the world’s people to make such a transition may be as follows:

- Sustainability: Developed nations must pledge to become net carbon negative in consumption emissions by 2030-35 to create space for developing nations to fully decarbonise by 2040-50. Decarbonisation must focus primarily on:

a) Mitigation focused on the reduction of consumption levels in the Global North, and supply-side management, leaving >90% of the remaining fossil fuel reserves in the ground;

b) Sequestration focused on Nature-based Solutions that centre climate and social justice. In addition, decarbonisation strategies must eschew failed, untested, hypothetical market-based solutions and techno-fixes. Through these means, gross global consumption should be reduced to sustainable levels, the measure for which should be a quantifiable justice-centric sustainability index.

- Environmental justice:

a) Responsibility for loss & damage: Nations/regions should take responsibility for climate change impacts attributable to them—displacement, property loss, etc—in proportion to their cumulative emissions (emissions from 1750 to date);

b) Sharing benefits and risks equitably: Engineering and administrative controls should be put into place (e.g., global warming mitigative and adaptive measures, facilitating population migration where risk becomes high) such that all people of the world face roughly the same degree of risk from the impacts of GHG emissions; and the wealth created by the use of fossil fuels are distributed equally to all people of the world.

- Equity: The ratio of the maximum to minimum income or alternatively energy consumption ratio for all people in the world, should be less than 5.

- Decentralisation, democratic, transparent governance: Governance should be decentralised and democratic; all governance information should be in the public domain.

- Environmental restitution: Degraded land, water, air, and to the extent possible, biodiversity should be restituted.

- Natural resource sharing: To engender global peace, people should share natural resources cooperatively and equitably as usufruct rights (and not ownership rights).

Whether the world’s vulnerable people will succeed in forming a global rainbow coalition and be able to agree on a radical programme to make society sustainable and equitable that will bring peace to the world is moot.

Cover image : Mundakkai and Chooralmala in Wayanad were washed away in devastating landslides on July 30, 2024. (PTI Photo)

The article was first published in Medico Friends Circle Bulletin # 385, August 2025, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://mfcindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/mfc-bulletin-385_compressed.pdf. Re-published by Countercurrents, 16 Sept 2025,