Carpenters Who Refused An Empire

In early 20th-century Kerala, the Asari (carpenter) caste resisted colonial and Brahminical systems by deliberately ignoring opportunities offered by colonial institutions. This act of refusal was a strategy against being shaped into compliant subjects within a hierarchical order. The article examines how this practice of ignoring influenced the community’s notion of progress. Sunandan K.N. writes

Politics of Ignoring: Stories of Asari Interventions in Colonial Practices in Malabar- Part 1

INTRODUCTION

By the end of the 19th century, various caste groups in the Malayalam-speaking region of Keralam began actively participating in colonial educational institutions. Historians of the region have mapped various caste communities’ interactions with colonial knowledge under the category of community reform. Education was central to all modern social reformers throughout India, from Jyotiba Phule to Ayyankali to upper-caste Bengali reformers. Historians of reform movements in India considered community reform movements as reactions to the colonial attempts at modernisation of British India, and modern education was central to this process of modernisation. In other words, in a modernising world, they believed, given an opportunity, every community and individual will seek knowledge, as knowledge is intrinsically connected to the natural desire of human beings for welfare and progress.

However, a close observation of the Asari (carpenter caste in Keralam) world in the first half of the 20th century tells us a different story. By actively ignoring/avoiding opportunities provided by the colonisers, Asaris resisted the invitation extended through various colonial institutions to be part of the colonial-Brahminical knowledge practice. This article will explore the strategies through which Asaris mobilised the practice of ignoring and its implications on the ‘progress’ of the community.

The exploration of subaltern practices in the past has always been a challenge to historians, as traces of these practices are either erased or are not easy to assimilate into the language of historical writing. To overcome this challenge, I am exploring, along with the colonial archives, scattered conversations, fragmented memories, stories, and rare written materials like a palm leaf manuscript. This methodology will necessarily not allow for a clear evidence-based positivist narrative. Hence, the following sections are more in the form of storytelling than a historical essay.

Before entering into the colonial world of assimilation and the Asari world of ignoring, a brief explanation of two conceptual categories – ‘politics of ignoring’ and ‘desham’ – used in this article is appropriate. The phrase ‘politics of ignoring’ attempts to explain the non-involvement of Asaris in colonial knowledge practices. In colonial narratives and in much of historical scholarship, this non-involvement is understood as part of the general ‘ignorance’ of subaltern communities. In the historical writings on religious and community reform movements, participation in modern educational practices is understood as the first step in overcoming ignorance. This is true for many subaltern communities. However in the case of Asaris we can see another form of engagement, which I call active ignoring. Here non-involvement was not because the community was unaware of colonial-modern forms of knowledge practices, rather the opposite: it was a conscious and strategic decision not to participate in those activities. Hence, ignoring is used as a category to capture the political dimensions of Asari engagement with the colonial world.

Desham, which may be literally translated as locality, is used in this article as a conceptual category in order to understand the locatedness of asarippani (carpentry). It is important to state at the outset that it is not a category like gramam (village), which is central to colonial, Gandhian or nationalist imagination of artisanal practice. Locatedness in the case of desham is not just spatial but epistemological as well. The adherence to locality was not a sign of lack of universalism or lack of generalisability. It was part of the creation of generalisable knowledge through direct experience of the locality. Hence the knowledge produced was local but not parochial. This will be clearer when I explain in the following sections the specific ways in which Asaris understood space and time in asarippani.

COLONIAL ATTEMPTS AT ASSIMILATION

By the middle of the 19th century, the British colonial government in India established new governing practices, which differed significantly from the earlier forms of colonial administration. David Scott, using the Foucauldian notion of governmentality, describes this as a transformation from the ‘rule of force’ to the ‘rule of law’. In this new form, population became the basic unit of the governing process and self-governance the ultimate form of governmental control (Scott 1995). Though the military and the police still had important roles in controlling the population, education became one of the major activities of governing. This transformation was part of a wider colonialist recognition of knowledge as the organising category of governance and for arranging individuals and groups in a hierarchical order, both in the metropole and colony. A new political rationality and a new order of knowledge co-emerged and mutually constituted each other. This order assigned a specific position for each section of the population in a hierarchical series according to their assumed historical relation with knowledge.

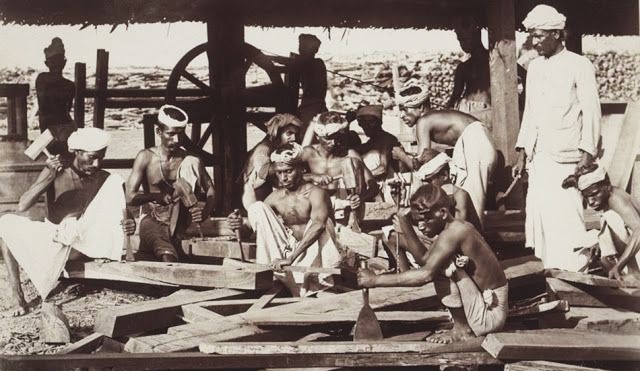

Artisans became the target of governing processes in the colonial attempt to order the population in a hierarchical series of knowledge. In attempting to govern, we can mark two important tactics developed by the colonialists. Firstly, the colonial government encouraged artisans to migrate from their supposedly natural locations in the villages to institutional spaces in cities and towns. Through this process of institutionalisation, the government hoped to bring artisanal practices under the visible eye of the state and transform it into a formal and regulated process. Secondly, the government initiated different programmes to standardise artisanal practices all over the country by implementing uniform methods and measures in artisanal production.

The colonial government assigned artisans an important role in their project of development based on towns and cities. In 1883, analysing the prospect of industrial development in the Madras state, E. B. Havell, the superintendent of the Madras School of Arts, argued that the native handicraft industry, rather than large factories, should be the central feature of the development of cities and towns. He observed that there were very few workshops and training centres in urban localities and the government should focus on providing economic support for carpenters and smiths to migrate to Madras and other small towns (Havell 1883). The committee that conducted a nationwide survey as part of industrial conferences in the first decade of the 20th century concluded that, though large-scale industries should be part of the long-term plan, developing handicraft- production-based small workshops and trading shops in towns was the best option given the contemporary socio-economic situation in India (Report on Industrial Education 1906).

Public works initiated by the government was another site of state intervention in artisanal practices. In 1875, the Madras government formed a new department for conducting and supervising public works. The Public Works Department (PWD) initiated the construction of roads, railways, bridges and buildings for which colonial officers in charge attempted to recruit traditional artisans and train them in using modern tools and methods. The government established a series of technical education institutions that would accommodate different sections of the population. While the colonialists considered general education a suitable domain for the upper castes, they imagined technical training as the proper and pertinent method of governing artisans. The Madras government attempted to recruit Asaris from Malabar for carpentry works related to railway, bridge and building construction under the PWD. The education department established various institutions such as schools of arts, industrial training centres and technical schools for training carpenters in modern methods of carpentry. All of these institutions and work sites were located in towns and cities.

From different colonial documents, we can see that both the above attempts – relocating artisans to workshops in cities and recruiting artisans to PWD-related institutions – did not succeed in general. Alfred Chatterton, who was the Superintendent of Industrial Education in the Madras government in the early years of the 20th century, explained the reluctance of artisans to join factory production:

We have found that the hand-weavers of Salem, like the hand-weavers of Madras, object to working in a factory, and although their wages were good, their attendance is unsatisfactory. This is mainly because the weavers prefer to work in their own home, assisted by their women and children, and dislike being subjected to the discipline and regular hours of working which must necessarily prevail in the factory (Chatterton 1902: 81).

Many colonial officers made similar remarks in the context of recruiting artisans into colonial institutions. E. B. Havell saw a connection between the failure of the various departments in the school in imparting quality training and the ‘shortage of apt students from the traditional castes for appropriate trades’ (Havell 1902: 87). In 1910, the director of the public instruction department of the Madras government reported that technical training schools, especially those in small towns, ‘serve no purpose because they completely failed in enlisting the children of traditional craftsmen such as carpenters, smiths and potters’ (Government of Madras 1910: 36).

The colonial documents of this period underlined Asari’s adherence to their desham (locality) as one of the major reasons for the above failure. In Malabar, like in many other places in the colony, the colonisers ‘targeted’ artisans and initiated different plans to relocate artisans to new institutional locations. For example, colonial officers in Malabar planned different strategies to recruit Asaris for PWD work and technical training in the early decades of the 20th century. The district collector of Malabar in 1907 recommended that the government use the traditional authority of educated landlords/upper castes to convince artisans of the advantages of joining in government works (Government of Madras 1909). He sent a detailed note to subordinate officers explaining the importance of improving traditional artisanal practices. After one year, he reported to the government that he ‘is still waiting for definite results of the new initiatives’. Many village-level officers reported that the Asaris were not ready to leave their village because by doing so they feared that they would become outcastes and would not be able to go back to their deshams (Government of Madras 1909: 22). The collector assured the lower-level native administrative officers under his authority that artisans who were ready to work in the PWD would be able to perform ‘the daily rituals they have to conduct according to their caste rules’, unless it violates ‘the rule of law and existing norms of work’ (Government of Madras 1909: 72). This clarification did not help much in convincing the artisans.

Six months later, the same collector reported to the government that he was now in contact with Christian missionaries who had established workshops in Calicut and Cannanore, where they imparted technical training to non-artisanal lower-caste converts. Protestant Christian missionaries who were active in Malabar were already using technical training as a method to teach the natives the importance of hard work and punctuality and the troubles of laziness. For the missionaries, physical industriousness was the first proof a native had to show to be accepted into the mission and Christianity. The Basel Mission Church of Calicut established several carpentry, weaving, and pottery workshops, the training in which was compulsory as probation for new aspirants for conversion to Christianity.

Colonial officers were reluctant to accept the newly trained and baptised workmen from missionary workshops for the works of the PWD. The Malabar collector mentioned that he ‘is worried about the quality of these workers because they are not from traditional craftsmen castes’ (Government of Madras 1910: 35). Here it is clear that the colonialists attempted not simply to create a labour force suitable for their economic policies but also to order the population as governable subjects by situating them in proper positions in a hierarchical system. In other words, in India, so-called modernisation projects were already cast through the prism of caste. Caste was a significant factor in the economic policies of the colonial government. Hence, the colonialists initiated these projects not only as economic activities but also as a process of governance in which no section of the population could be left out.

(To be continued)